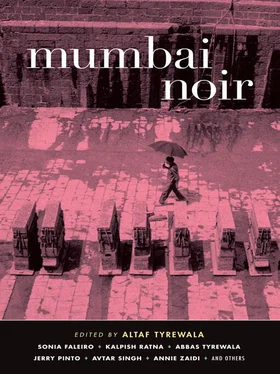

Altaf Tyrewala - Mumbai Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Altaf Tyrewala - Mumbai Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mumbai Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mumbai Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mumbai Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mumbai Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mumbai Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But time, relentless and unstoppable, very soon regained the ground it had lost to that momentary burst of aggrieved melancholy. As she boarded the train Sneha was already thinking about her work at school and the things she needed to buy for the evening meal, and it was only a little later that she realized that the burkha-clad lady sitting opposite her in the compartment was Salma. All her loss and sense of defeat, at not having received justice despite the verdict, came rushing back and she felt a strong desire to strike back and gain some semblance of victory.

“I didn’t see you in the courtroom but I am sure you must have heard the verdict. He is going to die; to be hanged until death, ” she tried to mimic the judge, and then the spite returned as she thought of Asghar. “He deserves to hang, bloody murderer.”

“Please don’t talk like that in front of his son,” Salma pleaded, totally unmindful of the sentence and Sneha’s spitefulness, as if they were natural. “He doesn’t know anything.”

Sneha persisted, not wanting to let go without extracting her revenge. “And how long will you keep him ignorant? His father’s photo is there on every TV channel and tomorrow it will be on the front page of every newspaper. Your son would have to be blind not to know about his father.”

“He is blind. He has never seen his father.”

A fast train whizzed past in the opposite direction on the adjacent track making a loud noise, and Sneha was happy for the distraction. With a single stroke of tragedy, nature had robbed her of her right to avenge.

“I am sorry,” she whispered, realizing the shallowness of her diatribe.

“Sorry for what?” Tears welled up in Salma’s already swollen eyes. “You have suffered earlier and now it is my turn. It is His way of delivering justice.”

Sneha wondered whether He delivered His justice in this manner; an eye for an eye, a death for a death, a widow for a widow; someone must have surely been blinded in the blast, she mused, looking at the child. The boy was staring blankly at her and she realized how in her bitterness she had failed to notice his condition, she who was a teacher at a school for the blind.

“Does he go to school?” she asked.

“School? Who would admit a blind child?”

“There are separate schools for the blind, even colleges. I teach at one.”

The future always rules the present and a faint hope lit up in Salma’s eyes.

“Will you teach him?” she asked, unmindful of her position, unmindful of the fact that the student’s father was the killer of the teacher’s husband.

Sneha needed no reiteration of the past. Their plight united them despite their religion, despite their peculiar positions, and their truce was unsaid and complete like it can only be between two women.

“I will get him admitted to my school. Come.”

The train was slowing down as it approached the station and Sneha and Salma stood up as if they had boarded with the sole purpose of getting the boy admitted to a school for the blind.

As the train stopped they alighted holding the blind child between them; two women left to live in a world where men delivered all the justice.

THE ROMANTIC CUSTOMER

BY PAROMITA VOHRA

Andheri East

Osama was sitting around in the cybercafé when our local cop, Jadhav, came in to put up a notice. It said:

Report any Suspicious Activity to the Police!

There could be a TERRORIST in your midst!

Protect the nation!

“You taking down all ID numbers and addresses in the register, right?” Jadhav asked me.

“Absolutely, saab,” I said.

What I wanted to say was: Jadhav, what about Osama here? Isn’t it suspicious that he is hiding inside the cybercafé instead of standing outside at the DVD stand, just when there’s a raid happening on the footpath vendors? Wonder who informed him, Jadhav? Couldn’t have been you now, could it? But it was no use joking with Jadhav. His sense of humor was Pvt. Ltd.: Only Laughs at Own Jokes.

“What, Jadhav, I heard you’ve bought a Nano,” Osama butted in. “When you taking us for a spin?”

Jadhav walked out without answering.

“He’s really bought a Nano?” I asked Osama.

“Then? You think he’ll buy a Mercedes-Benz or what? Mahakali bribes are too small-time, brother.”

“I don’t think you should needle Jadhav so much,” I said.

“Abbe, what can he do? If it weren’t for us, he’d be buying a purple Scooty Pep, not even a Nano.”

“It’s not us, big shot, it’s Haider bhai who pays him off,” I reminded Osama. Haider bhai was our boss — he owned the cybercafé, all the pirated DVD stands in Mahakali, and the Starlight DVD library on the corner.

“So? We’re a reflection of our boss, isn’t it? We’re his little bastards, aren’t we? Haan? Ha-ha-ha … haan?”

I ignored Osama, who by now had started fidgeting at one of the computers.

I’d worked for Haider bhai since I was eight. Those days VCRs were the craze. Haider bhai had set up shop in the Mahakali area, about eight stops from Mograwadi, where I live. For a hundred rupees a month I’d deliver VCRs to the chillar class who couldn’t afford to buy video players of their own. Three hundred rupees rent for Sunday, five hundred for overnight.

At that time, seventeen years ago, the neighborhood wasn’t very developed. Sometimes I’d go sit on top of the Mahakali Caves, which are supposed to be some ancient temples but were basically full of pissing bats and kissing couples. From there you could see the whole area — a few four-story buildings, hutments stacked up the hill like stadium steps, and the big leafy convent next to Holy Spirit hospital. Roses and jasmines bloomed in the windows of the transit camp houses. Ladies sat outside cleaning rice, while their cats and dogs slept in the sun. Nowadays, the view from the Caves is clogged by new sixteen-story buildings coming up, one after another, in clouds of red dust. And on the other side, far below the Caves, where there used to be only jungle, the new special economic zone, full of call centers, with walls like curving sheets of white silk.

The cybercafé I ran was in a semiconcrete market opposite a big residential complex. Two hundred square feet, with a tinted-glass front and booths with lockable doors covered in orange laminate. There was nothing dangerous about our customers— I could have told Jadhav that when he came with his stupid warning sign; that would be giving them too much credit.

Only losers and misers visited cybercafés those days — the kind who didn’t have their own computers or who were lying to their wives. Film strugglers from the PMGP tenements, college kids from the transit camp whose parents worked menial jobs, and unemployed fellows whose parents had managed to buy a one-bedroom place in one of the tackier new buildings. I’d read the chat histories of many. The art talk, the politics talk, the family-life talk — it all ended in some version of cybersex. No matter what, it was always the same — pretending to take an interest in each other when all you wanted was to have someone pay attention to you.

Like there was this dude, Prashant. Struggling actor, muscle-boy type. Wife had some fancy job, but the fellow still used the cybercafé. You could ask why but you don’t get answers by asking questions. Walked in pumped up from the gym and sagged like a relieved addict when he logged on. He sat there doing faltu Facebook chat with people better than him to convince himself that he was intrinsically above his own station in life. When you saw a guy like that you knew he’d eventually be careless. Sure enough, one day he forgot to log out. I went and read his chat. He was talking to some woman who claimed to be a TV writer in her profile. Not a hot type at all. He probably though she’d get him work.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mumbai Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mumbai Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mumbai Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.