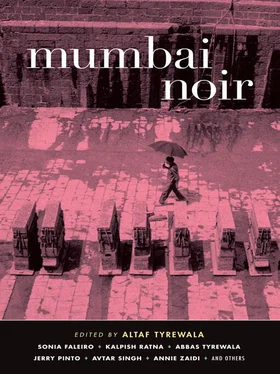

Altaf Tyrewala - Mumbai Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Altaf Tyrewala - Mumbai Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mumbai Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mumbai Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mumbai Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mumbai Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mumbai Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This promise of a “clean life” has driven millions of people over several centuries to abandon India’s rural hinterland and throng Mumbai’s streets in search of employment and social equality. It helps that under its urban façade, the city comprises numerous villagelike communal ghettos where people of similar religious and caste backgrounds can flock together. In Namita Devidayal’s piece, the wealthy, pill-popping homemaker resides in an “all-vegetarian” Jain building, where the appearance of a single nonvegan egg can wreak havoc. Anyone who has gone apartment hunting in Mumbai will testify that the city’s communal boundaries are often as impermeable as national borders.

The provincialism dictating who one’s neighbors may or may not be doesn’t, thankfully, extend to Mumbai’s commercial life. When it comes to making money, the city has been by and large blind to caste, class, or creed, exalting productivity and wealth-generation above all else. History has shown that in its unabashed pursuit of profit, Mumbai can also be deaf to considerations of ethics and morality.

Through the early half of the nineteenth century, a large number of local Parsi, Marwari, Gujarati Bania, and Konkani Muslim businessmen were involved in the opium trade, shipping Indian-grown opium out of Bombay to China, in direct competition with the British East India Company, which exported the product out of Calcutta. While millions of Chinese sunk into the despondency of addiction, Bombay’s capitalist classes grew staggeringly rich. The success of the opium trade, followed by the cotton boom in the 1860s, sparked the ascension of Bombay from a barely profitable port town to a roaring trade center. Much of the city’s infrastructural development, including its lasting social and educational institutions, was paid for with the dirty money of these local businessmen. It is a historical ethical conflict that the city has never quite faced up to.

Over the centuries, crime has remained at the service of commerce in a city that was cravenly capitalist long before the rest of the nation followed suit. If a demand exists— even for something as wishful as the “elixir of youth”—you can bet some enterprising chap in Mumbai will move heaven and earth to fulfill it. Even if it means having to strip human corpses of their testes, as the elixir-peddling hakim does quite profitably in Kalpish Ratna’s time-warping tale. In Sonia Faleiro’s unsettling glimpse into the city’s transgender subculture, death isn’t even a prerequisite: the dai earns her keep by relieving sentient (and willing) men of their jewels.

Paisa pheyko, tamasha dekho. Throw the cash, watch the dance. These words from an erstwhile Hindi film song have become the de facto motto of Mumbai. Cash can get things moving in a rusty bureaucracy. Cash can help you get away with murder. Sometimes a little cash can help you save big money.

In Mumbai’s dance bars, whole wads of cash must be thrown to get the women moving. Outlawed in 2005, these dens of misogyny and exploitation still manage to scrape through under the euphemistic moniker of “orchestra bars,” where the concept remains unchanged: tantalizingly dressed women dance or sing in front of a lusty male audience. No self-respecting tome on Mumbai would be complete without a riff on this seedy city institution. Avtar Singh’s story fulfills Mumbai Noir ’s dance-bar quota. To his credit, Singh infuses genuine romance into an overly romanticized setting.

Like its dance bars, Mumbai too has been heaped with exaggerated depictions in recent decades. The city’s chroniclers — its novelists, essayists, poets, journalists, and filmmakers — often seem overawed by the idea of Mumbai, rendering its quotidian realities in brushstrokes of grandiose narratives. What inoculates the stories in this collection from the hyperbole of “maximum city”—that much-abused term coined by the astute Suketu Mehta to describe Mumbai — are the restraints set by the noir genre, which stipulates, among other things, an unflinching gaze at the underbelly, without recourse to sentimentality or forced denouements. (But not without the courtesy of a glossary of Indianisms, to be found at the back of the book.) When viewed from a plane (or hotair balloon), any metropolis might strike one as jaw-dropping. For a majority of Mumbai’s residents, however, the city’s overcrowded public transportation and decaying infrastructure fail to provide even the minimum of relief.

Unending traffic. Sparse greenery. Corrupt governance. Mumbai always seems on the verge of a massive breakdown. What keeps the city somewhat peaceful and functioning is the very thing that makes it overwhelming: the population density, which is one of the highest in the world. Mumbai’s ever-present multitudes serve as eyes on the streets, pitching in during moments of crises, and at other times inhibiting acts of random violence. This has helped the city earn its reputation of being one of India’s safest urban centers.

While Mumbai’s civil society is remarkably accommodating to all varieties of lifestyles and individual preferences, perhaps the biggest threat to the city’s famed cosmopolitanism comes from its twin banes: Mumbai’s ultranationalist groups and its increasingly sectarian police force.

Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995 when an alliance of these ultranationalist groups controlled the state government. The renaming was meant as a symbolic undoing of the country’s colonial past. Ironically, other legacies of the British colonial rule were left untouched, such as Mumbai’s suburban rail system, its water and sewage infrastructure, as well as its enduring colonial-era architectural landmarks.

In December 1992 and January 1993, during the Hindu-Muslim riots that swept through Mumbai following the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the city’s police force, possibly for the first time in its history of serving the city, abandoned neutrality and sided with the Hindus, turning what would have been a routine communal skirmish into a catastrophic minipogrom. For the citizens of the city, and for its minorities in particular, the communalization of the police was the start of Mumbai’s darkest chapter. Devashish Makhija provides a heartrending depiction of cynical police officers let loose on Mumbai’s religious minorities. In this story, the international war on terror is echoed in Mumbai, turning every Muslim man into a suspect following a bomb blast. Riaz Mulla takes a converse approach, delineating how an ordinary businessman can turn into a bomb-planting extremist. Mulla looks unflinchingly at how events may have unfolded leading to Mumbai’s first terrorist attack.

In March 1993, in a misguided attempt to settle the score after the Babri Masjid riots, Mumbai’s Muslim-dominated underworld unleashed a series of thirteen bomb blasts throughout the city. The mastermind of these blasts, Dawood Ibrahim, was a Mumbai-born gangster operating out of the Middle East. Two hundred and fifty people lost their lives in the explosions and hundreds more were injured. (Those interested in understanding the often mundane genesis of headline-making terror attacks may look up Anurag Kashyap’s award-winning film Black Friday, based on S. Hussain Zaidi’s book Black Friday: The True Story of the Bombay Bomb Blasts .)

Since 1993, there have been no further communal riots in the city. Instead, in a kind of outsourcing of violence, Mumbai has been targeted by international terrorists no less than seven times. Each attack jars the city out of its intense commercedriven routines. But life resumes normalcy within hours, once the corpses and debris have been cleared out and the injured deposited in hospitals. Social commentators accuse Mumbai of a savage sort of indifference. Absolutely nothing seems to affect the city. Or maybe that’s a wrong way of looking at things. Maybe Mumbai isn’t just one city, but an organic conglomerate of innumerable subcities, each thrumming to its own vibe. A tragedy in one part of Mumbai barely registers elsewhere. People fall off moving trains, bombs erupt in busy bazaars, lives are made and broken in the city’s daily flux, and things go on as usual.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mumbai Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mumbai Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mumbai Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.