Dave Donaldson leaned over Skinny Arkle, felt in his pockets. He brought out a passport and a steamship ticket. That cinched the thing.

Skinny Arkle’s eyes fluttered. He mumbled: ‘Well — Turner... they won’t — hang me... you took... care of that... damn you...’ A spew of crimson gushed out of his kisser, and he folded up. And that was the end of Skinny Arkle.

Then I remembered Constance Calvert. She was slumped over in my jalopy. Arkle must have followed us; and maybe she’d spotted him. Anyhow, he’d tried to murder her quietly; probably figured on bumping Donaldson and me, too, when we came out of the hospital. He must have known the jig was up. But I wasn’t thinking about Skinny Arkle any more. I was thinking of the blonde Calvert wren.

She’d been choked unconscious; but she wasn’t seriously hurt. I turned to Dave Donaldson. I said: ‘Dave, you stay here and notify the Pasadena police — have them take Skinny’s carcass away.’

Dave said: ‘Where are you going?’

I said: ‘Well, I left this girl’s clothes in my apartment earlier tonight. So now I’m going to take her back to get ’em.’

‘Hell!’ Donaldson growled. ‘I’ll bet you won’t hurry about it.’

I said: ‘You flatter me, Dave.’ But it turned out that he was right, at that!

The Singing Pigeon

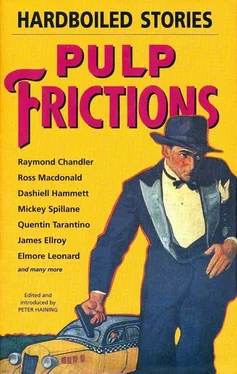

Ross Macdonald

Lew Archer is an ex-policeman from Long Beach, California, who was fired because he could not stomach the corrupt police administration he was forced to work for and instead became a private eye — the most famous of his ilk in fiction during the Sixties and Seventies. Described as a private man who operates most effectively in the shadows, he is still a ‘not unwilling catalyst for trouble’. He works from a small, bleak office, although this is surprisingly full of books (which he reads avidly when not working on a case), and the walls are hung with good modern paintings (his favourites are by the Japanese artist Kuniyoshi). Archer is unlike many of the other hardboiled dicks in that he does not indulge in promiscuous sex and has a real affinity with young people. He is also unique among his breed in being a vocal campaigner on behalf of a better environment. Immortalised on the screen by Paul Newman in The Moving Target (1966), in which he was inexplicably renamed Harper, and The Drowning Pool (1975), Archer has also featured in eighteen novels and a 1975 TV series starring Brian Keith.

The cop turned private eye was created by Ross Macdonald (1915–1983), the pseudonym of Kenneth Miller whom several critics have described as the heir to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Although Miller was born in California, he grew up in Canada with his mother who had separated from her husband. For a time he travelled in Europe and was then a teacher before meeting and marrying another writer, Margaret Strum, who introduced him to crime fiction. Although his early short stories and novels were popular, it was with the advent of Lew Archer that he became a household name. Anthony Boucher, the New York Times book reviewer who was among the first to spot the significance of Macdonald’s work, said that he was actually a better writer than either Hammett or Chandler and that his fiction had been responsible for developing the hardboiled private eye novel into a medium where there were ‘people with enough feeling to be hurt and enough complexity to do wrong’. Although Macdonald admitted to reading the hardboiled stories of many of his contemporaries, he claimed there was more of himself in the private eye than any outside influence. ‘The Singing Pigeon’, written in 1953, finds an exhausted Archer trying to get some rest in a motel after a fruitless chase to the Mexican border — and instead being plunged into the hunt for the killer of a man whose body is discovered in a car on a nearby beach.

* * *

It was Friday night. I was tooling home from the Mexican border in a light blue convertible and a dark blue mood. I had followed a man from Fresno to San Diego and lost him in the maze of streets in Old Town. When I picked up his trail again, it was cold. He had crossed the border, and my instructions went no further than the United States.

Halfway home, just above Emerald Bay, I overtook the worst driver in the world. He was driving a black fishtail Cadillac as if he was tacking a sailboat. The heavy car wove back and forth across the freeway, using two of its four lanes, and sometimes three. It was late, and I was in a hurry to get some sleep. I started to pass it on the right, at a time when it was riding the double line. The Cadillac drifted towards me like an unguided missile, and forced me off the road in a screeching skid.

I speeded up to pass on the left. Simultaneously, the driver of the Cadillac accelerated. My acceleration couldn’t match his. We raced neck and neck down the middle of the road. I wondered if he was drunk or crazy or afraid of me. Then the freeway ended. I was doing eighty on the wrong side of a two-lane highway, and a truck came over a rise ahead like a blazing double comet. I floorboarded the gas pedal and cut over sharply to the right, threatening the Cadillac’s fenders and its driver’s life. In the approaching headlights, his face was as blank and white as a piece of paper, with charred black holes for eyes. His shoulders were naked.

At the last possible second he slowed enough to let me get by. The truck went off into the shoulder, honking angrily. I braked gradually, hoping to force the Cadillac to stop. It looped past me in an insane arc, tyres skittering, and was sucked away into darkness.

When I finally came to a full stop, I had to pry my fingers off the wheel. My knees were remote and watery. After smoking part of a cigarette, I U-turned and drove very cautiously back to Emerald Bay. I was long past the hot-rod age, and I needed rest.

The first motel I came to, the Siesta, was decorated with a vacancy sign and a neon Mexican sleeping luminously under a sombrero. Envying him, I parked on the gravel apron in front of the motel office. There was a light inside. The glass-panelled door was standing open, and I went in. The little room was pleasantly furnished with rattan and chintz. I jangled the bell on the desk a few times. No one appeared, so I sat down to wait and lit a cigarette. An electric clock on the wall said a quarter to one.

I must have dozed for a few minutes. A dream rushed by the threshold of my consciousness, making a gentle noise. Death was in the dream. He drove a black Cadillac loaded with flowers. When I woke up, the cigarette was starting to burn my fingers. A thin man in a grey flannel shirt was standing over me with a doubtful look on his face.

He was big-nosed and small-chinned, and he wasn’t as young as he gave the impression of being. His teeth were bad, the sandy hair was thinning and receding. He was the typical old youth who scrounged and wheedled his living around motor courts and restaurants and hotels, and hung on desperately to the frayed edge of other people’s lives.

‘What do you want?’ he said. ‘Who are you? What do you want?’ His voice was reedy and changeable like an adolescent’s.

‘A room.’

‘Is that all you want?’

From where I sat, it sounded like an accusation. I let it pass. ‘What else is there? Circassian dancing girls? Free popcorn?’

He tried to smile without showing his bad teeth. The smile was a dismal failure, like my joke. ‘I’m sorry, sir,’ he said. ‘You woke me up. I never make much sense right after I just wake up.’

‘Have a nightmare?’

His vague eyes expanded like blue bubblegum bubbles. ‘Why did you ask me that?’

‘Because I just had one. But skip it. Do you have a vacancy or don’t you?’

Читать дальше