At first glance there is little connection between the tawdry office blocks, sleazy hotels and dimly lit bars of downtown Los Angeles and the quiet, leafy suburb of Dulwich in South London, yet in the colourful legend of hardboiled fiction they are inextricably linked. For it was a classical scholar from Dulwich College who, as a man, was to capture in story form the wisecracking, colloquial style of the LA citizens’ language and give crime fiction its most renowned private eye. His name was Raymond Chandler and his character was Philip Marlowe.

Although Chandler was an American born in Chicago, he was brought to England as a child and educated at Dulwich which, despite all the fame he later achieved in his homeland, made him a lifelong anglophile. This man, who relished the hexameters of Latin and Greek, is nevertheless best remembered for pioneering the use of the metaphors that are now regarded as characteristic of hardboiled fiction.

‘He pawed my office with his eyes,’ Philip Marlowe declares on one occasion, and then says of a visitor, ‘His tie had apparently been tied with a pair of pliers.’ And who would relish meeting a man described thus in Chandler-speak: ‘His smile was as stiff as a frozen fish’?

For years, Chandler’s links with Dulwich were scarcely known. Although he retained fond memories of the public school, founded more than 350 years ago, which he attended between 1900 and 1905, the establishment for its part did not even list ‘Pupil 5724’ (his college number) in its volume of famous old boys. The error was to some degree redressed in 1988 when some enthusiasts of the author’s work, knowing of the connection, decided to mark the centenary of his birth with an exhibition of memorabilia. It was only then that the influence of Chandler’s education was seen in the character of Philip Marlowe. Where else could the private eye’s ability to quote the classics have come from? More striking still was the college’s association with the famous sleuth’s name — a name so English-sounding that for years readers had puzzled over its possible origins. The answer again lay at Dulwich, for in the early 1900s when Chandler was a pupil, the college boasted six houses: Drake, Grenville, Raleigh, Sidney, Spencer and... Marlowe.

Even more recently, evidence has emerged in the form of a typewritten letter purchased as part of another crime writer’s effects, revealing Chandler’s love of England and his desire to return here after the death of his beloved wife in December 1954. The letter was written by the English mystery novelist Nicholas Bentley, proposing that Chandler should be allowed to join the exclusive Garrick Club in London. It is dated June 1955 and is addressed to a Mr George at the club:

I wonder if you would care to sign the book at the Garrick Club in support of Raymond Chandler, whom I have just proposed and whom Malcolm Muggeridge has seconded. Chandler has come over to stay in this country indefinitely, I think with the idea of ultimately settling down here, and would very much like to join the Club. Unfortunately he is not known personally to more than a few members, so if you would feel inclined to sign the book on his behalf, I am sure it would be a great help.

There can be few more poignant letters about the still mourning and lonely Chandler than this one, with its suggestion that he wanted to leave the country that had made him famous and spend his remaining years in England. But why? Nicholas Bentley’s missive suggests more than it explains and surely offers a mystery worthy of Marlowe’s talents.

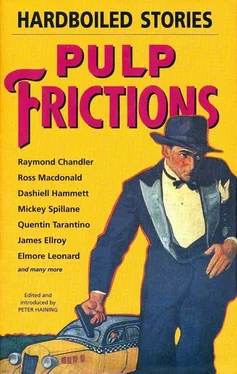

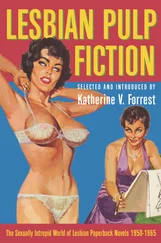

Like so much of the lore and legend surrounding hardboiled fiction, there are still many stories to be unearthed not only about the authors, but also about the pulp magazines in which they appeared — so called because they were printed on cheap, untrimmed wood-pulp paper, octavo size, and stapled inside a slick paper cover printed in garish colours. Few copies survive of these magazines, which rapidly yellowed and fell into fragments, while many of the writers are now no more than names on the pages, having disappeared completely, either by choice or design, when the industry folded in the 1950s. Some of the authors, like Chandler, survived to make the transition into the permanency of book form, to be followed by recognition when the true scope of their achievement was realised: the creation of the first truly original American style of detective fiction. It is these men and the spirit of their forgotten colleagues that have been the inspiration for today’s upsurge of interest in, and new contributions to, the hardboiled genre.

The hardboiled dick is now as much a part of American folklore as the frontiersman and the cowboy, and like most heroes his exploits are often exaggerated. Indeed, his seemingly limitless capacity for drink, and his amazing ability to recover from beatings, blows to the head, and knife and gunshot wounds, coupled with his need for only an hour or two’s sleep at night, are almost superhuman. Certainly no ordinary mortal could match him. A similar view might be taken of some of the tough cops and gangsters who provided the other main elements in the genre.

But what made these almost caricature-like figures so popular? The answer, I suggest, is not too hard to find. The first of the hardboiled dicks were born in the age of disillusionment in America that followed the First World War, when there was intense frustration among many people about the way organised crime, in the shape of high-profile mobsters and hoods, was taking control of the big cities, their politicians and civic officials, and filling the streets with speakeasies, gambling joints and vice-spots, all packed with low-life. The private eye who emerged in pulp fiction was an almost romantic figure, bent on a crusade against this cancer in society, although he had none of the finer feelings for language, took immediate action (usually brutal) and was dedicated to the preservation of justice. No matter the cost to his limbs — or anyone else’s, for that matter!

The explanation for today’s new wave of interest in this kind of fiction has a similar origin, I believe: many people, especially the younger generation, feel an equal sense of frustration and disillusionment towards society and their grim prospects for the future. As Ian Penman wrote recently in The Independent about Jim Thompson, his hero among the pulp writers: ‘He has grabbed our moral imagination: providing — and provoking — strong passions in a lily-livered time; a time which perhaps thinks do-goodery can wash the elemental guilt from our hands, when the persistence of evil is clearly inescapable.’

In another article, in the American magazine New Republic , a leader writer attempts to define the current hardboiled genre — American Noir, as he calls it — of which Elmore Leonard, James Ellroy and Quentin Tarantino are the leading exponents. It is, he concludes, ‘the moral phenomenology of the depraved or ruined middle class’.

It is not, however, my intention to indulge in a sociological study of hardboiled fiction, but merely to introduce what I believe to be a representative selection of stories by the most influential writers in the genre spanning the last three-quarters of a century. Reading through the precious copies of the pulp magazines that still exist, to find stories that have not been reprinted before or else are not easily available, has been, for me, a return journey to a treasure chest I explored earlier, before the current boom in hardboiled fiction. Twenty years ago I assembled the first collection published in Britain of material from these magazines, entitled The Fantastic Pulps (1975) and now out of print, to be followed a year later by a facsimile reprint of stories from one of my favourite pulps, Weird Tales , complete with the original text and illustrations. Only the paper quality and packaging — in hard covers — were an improvement on the original. In 1976 I also compiled Terror! A History of Horror Illustrations from the Pulp Magazines , and in 1977 Mystery! An Illustrated History of Crime and Detective Fiction which included numerous covers and interior illustrations from the hardboiled pulps, including Black Mask, Detective Fiction Weekly, Dime Mystery and so on. It was the publisher of those two volumes who invited me to compile this new anthology.

Читать дальше