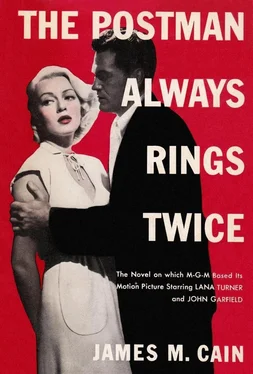

James Cain - The Postman Always Rings Twice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Cain - The Postman Always Rings Twice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1934, Издательство: Grosset & Dunlap, Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Postman Always Rings Twice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grosset & Dunlap

- Жанр:

- Год:1934

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Postman Always Rings Twice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Postman Always Rings Twice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Postman Always Rings Twice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Postman Always Rings Twice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“O.K.”

He hung up. I walked over and gave him a sock. “That’s just so you talk right when he calls back. You got it, Kennedy?”

“I got it.”

I waited a few minutes, and pretty soon here came the call back. I answered, and when Kennedy picked up the phone he gave Willie some more of the same. He said he was alone that time. Willie didn’t like it much, but he had to take it. Then I took him back to the No. 1 shack. She came with us, and I took the gun. Soon as I had Kennedy inside, I stepped out the door with her and gave her a kiss.

“That’s for being able to step on it when the pinch comes. Now get this. I’m not leaving him for a minute. I’m staying out here the whole night. There’ll be other calls, and we’ll bring him in to talk. I think you better open the place up. The beer garden. Don’t bring anybody inside. That’s so if his friends do some spying, you’re right on deck and it’s business as usual.”

“All right. And Frank.”

“Yes?”

“Next time I try to act smart, will you hang one on my jaw?”

“What do you mean?”

“We ought to have gone away. Now I know it.”

“Like hell we ought. Not till we get this.”

She gave me a kiss, then. “I guess I like you pretty well, Frank.”

“We’ll get it. Don’t worry.”

“I’m not.”

I stayed out there with him all night. I didn’t give him any food, and I didn’t give him any sleep. Three or four times he had to talk to Willie, and once Willie wanted to talk to me. Near as I could tell, we got away with it. In between, I would beat him up. It was hard work, but I meant he should want that paper to get there, bad. While he was wiping the blood off his face, on a towel, you could hear the radio going, out in the beer garden, and people laughing and talking.

About ten o’clock the next morning she came out there.

“They’re here, I think. There are three of them.”

“Bring them back.”

She picked up the gun, stuck it in her belt so you couldn’t see it from in front, and went. In a minute, I heard something fall. It was one of his gorillas. She was marching them in front of her, making them walk backwards with their hands up, and one of them fell when his heel hit the concrete walk. I opened the door. “This way, gents.”

They came in, still holding their hands up, and she came in after them and handed me the gun. “They all had guns, but I took them off them in the lunchroom.”

“Better get them. Maybe they got friends.”

She went, and in a minute came back with the guns. She took out the clips, and laid them on the bed, beside me. Then she went through their pockets. Pretty soon she had it. And the funny part was that in another envelope were photostats of it, six positives and one negative. They had meant to keep on blackmailing us, and then hadn’t had any more sense than to have the photostats on them when they showed up. I took them all, with the original, outside, crumpled them up on the ground, and touched a match to them. When they were burned I stamped the ashes into the dirt and went back.

“All right, boys. I’ll show you out. We’ll keep the artillery here.”

After I had marched them out to their cars, and they left, and I went back inside, she wasn’t there. I went out back, and she wasn’t there. I went upstairs. She was in our room. “Well, we did it, didn’t we? That’s the last of it, photostats and all. It’s been worrying me, too.”

She didn’t say anything, and her eyes looked funny. “What’s the matter, Cora?”

“So that’s the last of it, is it? Photostats and all. It isn’t the last of me, though. I’ve got a million photostats of it, just as good as they were. Jimmy Durante. I’ve got a million of them. Am I mortified?”

She burst out laughing, and flopped down on the bed.

“All right. If you’re sucker enough to put your neck in the noose, just to get me, you’ve got a million of them. You sure have. A million of them.”

“Oh, no, that’s the beautiful part. I don’t have to put my neck in the noose at all. Didn’t Mr. Katz tell you? Once they just made it manslaughter, they can’t do any more to me. It’s in the Constitution or something. Oh no, Mr. Frank Chambers. It don’t cost me a thing to make you dance on air. And that’s what you’re going to do. Dance, dance, dance.”

“What ails you, anyhow?”

“Don’t you know? Your friend was out last night. She didn’t know about me, and she spent the night here.”

“What friend?”

“The one you went to Mexico with. She told me all about it. We’re good friends now. She thought we better be good friends. After she found out who I was she thought I might kill her.”

“I haven’t been to Mexico for a year.”

“Oh yes you have.”

She went out, and I heard her go in my room. When she came back she had a kitten with her, but a kitten that was bigger than a cat. It was gray, with spots on it. She put it on the table in front of me and it began to meow. “The puma had little ones while you were gone, and she brought you one to remember her by.”

She leaned back against the wall and began to laugh again, a wild, crazy laugh. “And the cat came back! It stepped on the fuse box and got killed, but here it is back! Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha! Ain’t that funny, how unlucky cats are for you?”

Chapter 15

She cracked up, then, and cried, and after she got quiet she went downstairs. I was down there, right after her. She was tearing the top flaps off a big carton.

“Just making a nest for our little pet, dearie.”

“Nice of you.”

“What did you think I was doing?”

“I didn’t.”

“Don’t worry. When the time comes to call up Mr. Sackett, I’ll let you know. Just take it easy. You’ll need all your strength.”

She lined it with excelsior, and on top of that put some woolen cloths. She took it upstairs and put the puma in it. It meowed a while and then went to sleep. I went downstairs to fix myself a coke. I hadn’t any more than squirted the ammonia in it than she was at the door.

“Just taking something to keep my strength up, dearie.”

“Nice of you.”

“What did you think I was doing?”

“I didn’t.”

“Don’t worry. When I get ready to skip I’ll let you know. Just take it easy. You may need all your strength.”

She gave me a funny look and went upstairs. It kept up all day, me following her around for fear she’d call up Sackett, her following me around for fear I’d skip. We never opened the place up at all. In between the tip-toeing around, we would sit upstairs in the room. We didn’t look at each other. We looked at the puma. It would meow and she would go down to get it some milk. I would go with her. After it lapped up the milk it would go to sleep. It was too young to play much. Most of the time it meowed or slept.

That night we lay side by side, not saying a word. I must have slept, because I had those dreams. Then, all of a sudden, I woke up, and before I was even really awake I was running downstairs. What had waked me was the sound of that telephone dial. She was at the extension in the lunchroom, all dressed, with her hat on, and a packed hat box on the floor beside her. I grabbed the receiver and slammed it on the hook. I took her by the shoulders, jerked her through the swing door, and shoved her upstairs. “Get up there! Get up there, or I’ll—”

“Or you’ll what?”

The telephone rang, and I answered it.

“Here’s your party, go ahead.”

“Yellow Cab.”

“Oh. Oh. I called you, Yellow Cab, but I’ve changed my mind. I won’t need you.”

“O.K.”

When I got upstairs she was taking off her clothes. When we got back in bed we lay there a long time again without saying a word. Then she started up.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Postman Always Rings Twice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Postman Always Rings Twice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Postman Always Rings Twice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.