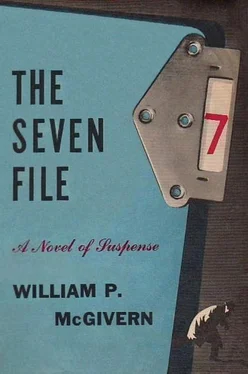

William McGivern - The Seven File

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William McGivern - The Seven File» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1956, Издательство: Dodd, Mead & Company, Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Seven File

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dodd, Mead & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1956

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Seven File: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Seven File»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Seven File — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Seven File», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Well, it will be pleasant for you, sir. Seeing Mrs. Bradley and Jill again.”

“Yes, yes, of course.”

While Anderson was packing his grip Mr. Bradley put in a call to Joe Piersall. A baby girl watched him from a silver frame on his desk. Round and rosy as an apple, with doll-like curls and dimples, she beamed out at the world with a sense of breathless wonder and excitement. He had made her smile for that picture, he remembered; the photographer, a stupid, clucking fool, had only frightened her, and Ellie and Dick hadn’t done much better. But he had got her laughing... the old trick of staring solemnly at her and widening his eyes very slowly had done it. Suddenly he slammed his fist down on the desk. Don’t get excited, Playton had said. Damn Playton! He had never known such a cold, deliberate fury in all his life. They would pay for this. Every dollar he owned would be used to hunt them down...

The Piersalls’ butler told him that Mr. Piersall had gone for a walk in the woods but was expected back for tea. Mr. Bradley left a message asking Piersall to call him back the minute he came in.

Replacing the phone he stood and walked around the room, rubbing his hands together anxiously. Gone since Saturday night at least. But where was the nurse? The Irish girl, Kate. Dick hadn’t even mentioned her. Was she involved in this?

He drank the brandy Anderson had brought him, but it didn’t dissolve the nervous pain in his stomach. A sudden terrible fear had gripped him; Jill was already dead. Why should they let her live? The money would be paid anyway. A finger’s pressure on her throat, a few spadesful of earth on her body, and she wouldn’t cause them any more trouble.

Yes, she was dead. He was sure of that. And all of his own foolish dreams were dead. Of being around when she started to talk, of watching her learn to ride, of summers with her at the big old place at James Harbor. They never went there any more. It was made for children... Ellie wouldn’t have minded, he thought, rubbing a hand over his eyes. These were the dreams that had kept him alive. Bait, nothing more. The carrot in front of a tired donkey. Fooling himself with Playton’s blessing. “Just to see her, that’s all I want.” The only grandchild he would ever see. “That will satisfy me completely. I’m not asking for the moon, am I?” That was the start of it. And then; “I’d like to hear her talking.” And: “If I could see her in a party dress — they start early, you know.” An old dreaming fool. Encouraged by Playton.

He stared at the baby’s picture, fighting back his tears. He couldn’t help her, he couldn’t spare her an instant of fear and pain. With all his money, all his influence...

The phone rang and he lifted the receiver quickly. “Joe? This is terribly important. Can you talk? Are you alone?”

“I’m in my study, and the door is closed. Why?”

“All right, listen closely, Joe. I can’t repeat this.”

“Yes, yes. Shoot.”

“Get this then.” Oliphant Bradley’s voice was low and harsh. “I need two hundred thousand dollars tonight. Within the next two hours. I need—”

“Ollie, for God’s sake—”

“Listen to me. The bills must he in denominations of five, ten and twenty. They must be old.”

“Good God! When did this happen?”

“I can’t tell you on the phone. I’ll be at your bank in an hour. And I want a plane standing by for me when we’ve got the money counted.”

“Certainly.” Piersall’s voice sharpened. “I’ll call two of my managers to help us. And I’ll have my son arrange for the plane. I’ll see you in an hour, Ollie.”

Bradley put the phone down and rubbed the tips of his fingers over his forehead. Yes, they would pay the money. That was the least of it. There were fifty men he might have called, but Joe Piersall happened to be the handiest. The money meant nothing. It would go into the hands of human scum who had already murdered his son’s baby. And would they ever be caught? Ever punished? Not by tired old men and frightened parents. Dick and Ellie didn’t want the police brought in. It might be weeks before they faced the brutal fact that their baby was dead. And then it would be too late. The trail would have vanished; already it was cold. What did Dick and Ellie know about such things? he thought. They were hysterical children, unable to think or plan.

A knock sounded and Anderson looked in on him. “Your bag is ready, sir. And will you have tea?”

“No — no, thanks. I’ll have something downtown.”

When the door closed Mr. Bradley reached slowly for the phone. His old face was suddenly set in hard, bitter lines. This wasn’t his decision to make — but by God he would make it. He knew best. That’s what mattered. He picked up the phone and cleared his throat. When the operator answered, he said, “Get me the FBI, please. Right away.”

Seven

At seven-thirty on Sunday night the phone rang at the lodge. Duke was sitting before the fireplace, sprawled comfortably in his chair, a cold cigar in the fingers of his trailing hand. He was nodding drowsily and his dark, strong face was flushed with the heat from the log fire. The room was warm and snug, the old furniture and flooring gleaming softly under lamplight, the windows and doors closed against the storm that had sprung up in the gathering darkness. Wind and rain drove against the sides of the house in swerving erratic bursts, buffeting them with great banging blows.

Grant was pacing the floor, drawing nervously on his cigarette, and occasionally glancing at his wrist watch. He looked tense and preoccupied; his heavily muscled body was clumsy with strain and his eyes were on the move constantly, switching from side to side, pointlessly checking the comers of the room, the shadows thrown by the spurting flames.

When the phone rang he turned and stared at Duke. “It’s the phone,” he said.

“You were expecting maybe something by Mozart?” Duke said, grinning at him.

“Cut it out,” Grant said sharply.

“Cut what out? Pick up the phone.”

“Sure, sure,” Grant said. Crossing the room quickly, he lifted the receiver and said, “Yes,” in a cautious voice. He listened for a few seconds, frowning faintly, and then, little by little, his expression cleared and a smile began to turn the comers of his lips. “Good,” he said. He drew a deep breath. “That’s fine.”

Duke looked at Grant. “Tell him not to start spending the dough yet.”

Grant made an impatient gesture with his hand. “So far, so good then,” he said, speaking into the phone. “But we’ve had a mix-up. I can’t get back to New York. You know what that means?” He listened, shaking his head slowly. “No, I can’t tell you on the phone. You understand what it means?” Finally, after another pause, he said, “That’s right. There’s nothing to it. It’s all worked out. We’ll be in touch right along, of course. If there’s any question at all, let me know. Yes, yes. Of course...”

When Grant put the phone back in place, he came over and sat down beside Duke. He lit a cigarette and patted his damp forehead with a handkerchief. Some of the tension had eased in his big body. “So far, so good,” he said, glancing sideways at Duke. “The Bradleys got home at five. Creasy saw them pick up the note. They went inside, and that was that. The housekeeper got in at six. Nobody else showed.”

“They’ll do what they’re told,” Duke said, stretching his arm over his head. “They want the kid back. How’s Creasy? All charged up?”

“He sounds fine. He’s going to handle the payoff. We worked out the plan between us, you know. He’s studied every step.” Grant smiled then, but he was watching Duke’s profile from the corners of his eyes. “He can handle it just as well as I could. He’s a damn shrewd little guy.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Seven File»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Seven File» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Seven File» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.