His voice had gone up in volume. I stared at him, puzzled, wondering if he was a little crazy, or if he was just trying to keep up the argument by thinking up screwy loopholes.

I said: “Then if nobody knows if he’s deaf, nobody knows if there was any sound.”

He said: “You’re wrong, mister. That man would know whether he heard it or not. Maybe the tree would know, wouldn’t it? And maybe other people would know, too.”

“I don’t get your point,” I told him. “What are you trying to prove?”

“ Murder, mister. You just got up from sitting next to a murderer.”

I stared at him again, but he didn’t look crazy. Far off, a train whistled, faintly. I said: “I don’t understand you.”

“The guy sitting on the bench,” he said. “Bill Meyers. He murdered his wife. Her and his hired man.”

His voice was quite loud. I felt uncomfortable; I wished that far train was a lot nearer. I didn’t know what went on here, but I knew I’d rather be on the train. Out of the corner of my eye I looked at the tall man with the granite face and the big hands. He was still staring out across the tracks. Not a muscle in his face had moved.

The station agent said: “I’ll tell you about it, mister. I like to tell people about it. His wife was a cousin of mine, a fine woman. Mandy Eppert, her name was, before she married that skunk. He was mean to her, dirt mean. Know how mean a man can be to a woman who’s helpless?

“She was seventeen when she was fool enough to marry him seven years ago. She was twenty-four when she died last spring. She’d done more work than most women do in a lifetime, out on that farm of his. He worked her like a horse and treated her like a slave. And her religion wouldn’t let her divorce him or even leave him. See what I mean, mister?”

I cleared my throat, but there didn’t seem to be anything to say. He didn’t need prodding or comment. He went on.

“So how can you blame her, mister, for loving a decent guy, a clean, young fellow her own age, when he fell in love with her? Just loving him, that’s all. I’d bet my life on that, because I knew Mandy. Oh, they talked, and they looked at each other — I wouldn’t gamble too much there wasn’t a stolen kiss now and then. But nothing to kill them for, mister.”

I felt uneasy; I wished the train would come and get me out of this. I had to say something, though; the agent was waiting. I said: “Even if there had been, the unwritten law is out of date.”

“Right, mister.” I’d said the right thing. “But you know what that bastard sitting over there did? He went deaf.”

“Huh?” I said.

“He went deaf. He came in town to see the doc and said he’d been having earaches and couldn’t hear any more. Was afraid he was going deaf. Doc gave him some stuff to try, and you know where he went from the doc’s office?”

I didn’t try to guess.

“Sheriff’s office,” he said. “Told the sheriff he wanted to report his wife and his hired man were missing, see? Smart of him. Wasn’t it? Swore out a complaint and said he’d prosecute if they were found. But he had an awful lot of trouble getting any of the questions the sheriff asked. Sheriff got tired of yelling and wrote ’em down on paper. Smart. See what I mean?”

“Not exactly,” I said. “Hadn’t his wife run away?”

“He’d murdered her. And him. Or rather, he was murdering them. Must have taken a couple of weeks, about. Found ’em a month later.”

He glowered, his face black with anger.

“In the smokehouse,” he said. “A new smokehouse made out of concrete and not used yet. With a padlock on the outside of the door. He’d walked through the farmyard one day about a month before — he said after their bodies were found — and noticed the padlock wasn’t locked, just hanging in the hook and not even through the hasp.

“See? Just to keep the padlock from being lost or swiped, he slips it through the hasp and snaps it.”

“My God,” I said. “And they were in there? They starved to death?”

“Thirst kills you quicker, if you haven’t either water or food. Oh, they’d tried hard to get out, all right. Scraped halfway through the door with a piece of concrete he’d worked loose. It was a thick door. I figure they yelled, after a while. I figure they hammered on that door plenty. Was there sound, mister, with only a deaf man living near that door, passing it twenty times a day?”

Again he chuckled humorlessly. He said: “Your train’ll be along soon. That was it you heard whistle. It stops up by the water tower. It’ll be here in ten minutes.” And without changing his tone of voice, except that his tone got louder again, he said: “It was a bad way to die. Even if he was right in killing them, only a black-hearted son of a gun would have done it that way. Don’t you think so?”

I said: “But are you sure he is—”

“Deaf? Sure, he’s deaf. Can’t you picture him standing there in front of that padlocked door, listening with his deaf ears to the hammering inside? And the yelling?

“Sure, he’s deaf. That’s why I can say all this to him, yell it in his ear. If I’m wrong, he can’t hear me. But he can hear me. He comes here to hear me.”

I had to ask it. “Why? Why would he — if you’re right.”

“I’m helping him, that’s why. I’m helping him to make up his black mind to hang a rope from the grating in the top of that smokehouse, and dangle from it. He hasn’t got the guts to, yet. So every time he’s in town, he sits on the platform a while to rest. And I tell him what a murdering son of a gun he is.”

He spat toward the tracks. He said: “There are a few of us know the score. Not the sheriff; he wouldn’t believe us, said it would be too hard to prove.”

The scrape of feet behind me made me turn. The tall man with the huge hands and the granite face was standing up now. He didn’t look toward us. He started for the steps.

The agent said: “He’ll hang himself, pretty soon now. He wouldn’t come here and sit like that for any other reason, would he, mister?”

“Unless,” I said, “he is deaf.”

“Sure. He could be. See what I meant? If a tree falls and the only man there to hear it is maybe deaf and maybe not, is it silent or isn’t it? Well, I got to get the mail pouch ready.”

I turned and looked at the tall figure walking away from the station. He walked slowly and his shoulders, big as they were, seemed a little stooped.

The clock in the steeple a block away began to strike for eight o’clock.

The tall man lifted his wrist to look at the watch on it.

I shuddered a little. It could have been coincidence, sure, and yet a little chill went down my spine.

The train pulled in, and I got aboard.

Arson Plus

Peter Collinson

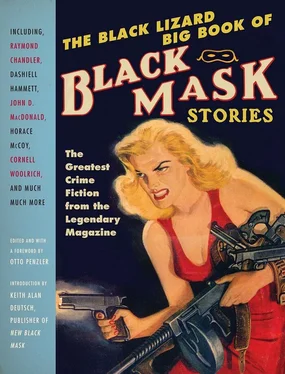

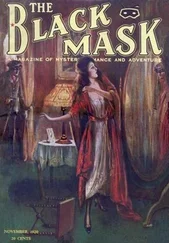

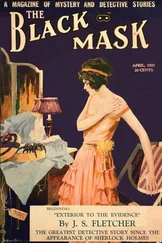

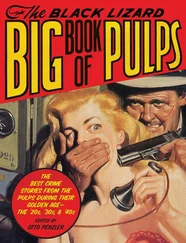

Peter Collinson is the pseudonym of (Samuel) Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961), who was born in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, and served in the Motor Ambulance Corps during World War I; he also served in the Signal Corps during World War II, mostly on the Aleutian Islands. He worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency in several cities, including Baltimore, San Francisco (where he got a promotion for catching a man who had stolen a Ferris wheel), and Los Angeles, where he was involved in the rape case that ruined the then-famous comic actor Fatty Arbuckle; he was also once assigned to follow the notorious gangster Nick Arnstein. His years as a detective provided rich background for his crime stories, and he discovered early on that the pulp magazine market was a good one.

Although he is recognized as one of the giants in the history of the American hard-boiled school of fiction, Hammett produced only five novels and a modest number of short stories, especially when compared with the output of other successful pulp writers. After a few fairly trivial pieces for the Smart Set magazine, he wrote his first crime story and submitted it to Black Mask under the pseudonym Peter Collinson. In the underworld argot of the day, a “Peter Collins” was a nobody. Hammett added the “on” to make the name read, literally, “nobody’s son.”

Читать дальше