She gave a quick glance around, then tilted her head, and pursed her lips.

“Come and get it,” she challenged.

Fifteen minutes later, when I had started down the street to get those checks cashed, a dirty urchin thrust a paper in my hand.

“The man said there’d be an answer,” he said, peering up at me with his young-old, wise eyes.

I unfolded the paper.

“You can’t make it stick,” read the note. “Other papers are outstanding and will be used in a way to ruin persons you would protect. Give this lad an answer, stating when and where you will turn over the commissions. I mean to have those space checks. That money is to come to me. Where do I get it and when?”

The note was unsigned. It didn’t need a signature. I had jarred old Icy-Eyes out of his calm. I grinned, took a pencil from my pocket and started to scribble an answer, and then those words of Helen Chadwick’s came to my mind. I chuckled and scribbled my message of defiance on the back of the note.

“COME AND GET IT,” I wrote, and handed the paper back to the boy.

“The answer is on the back,” I told him, and with that I started on my way, knowing that they would try to follow me, knowing also that I must thrust aside the ways of civilized society and vanish within the shadows, knowing that this conflict with the icy-eyed criminal would never cease until one of us had written “In Full of Account” against the life of the other. But in the meantime I had turned the tables, had got the police guessing, and had seen Helen Chadwick again — that joyous little flapper who was such a baffling combination of vivacious frivolity and courageous fortitude, that girl who was commencing to be so much in my thoughts.

Let Icy-Eyes come and get it. He would find a warm reception waiting him.

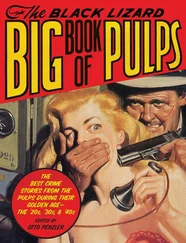

Cry Silence

Fredric Brown

Fredric Brown (1906–1972) was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and attended the University of Cincinnati and Hanover College before becoming an office worker from 1924 to 1936. He then took a job as a proofreader and reporter for the Milwaukee Journal. A chronic respiratory problem caused him to move to Taos, New Mexico, then Tucson, Arizona. While at the Journal, he sold his first short story and went on to publish more than three hundred stories in his lifetime, as well as nearly thirty novels, in both the science fiction and mystery genres.

Equally revered by fans of science and mystery fiction, Brown was one of the most original, creative pulp writers of his time, his stories often having astonishing twists and surprise endings, frequently leavened with humor. His first mystery novel, The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947), won an Edgar Allan Poe Award and introduced the detective team of Ed Hunter and his uncle Am, who appeared in six subsequent novels.

Brown wrote scripts for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and several television dramas and films were made from his books, notably Crack-Up (1946, RKO, starring Pat O’Brien, Claire Trevor, and Herbert Marshall), based on his short story “Madman’s Holiday,” and The Screaming Mimi (1958, Columbia, starring Anita Ekberg, Phil Carey, and Gypsy Rose Lee), based on the novel of the same name.

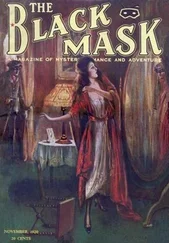

“Cry Silence” was published in the November 1948 issue.

Would you try to save your wife from a killer? Seems like a simple question, but to Mandy’s husband, it was one to stump the experts.

* * *

It was that old silly argument about sound. If a tree falls deep in the forest where there is no ear to hear, is its fall silent? Is there sound where there is no ear to hear it? I’ve heard it argued by college professors and by street sweepers.

This time it was being argued by the agent at the little railroad station and a beefy man in coveralls. It was a warm summer evening at dusk, and the station agent’s window opening onto the back platform of the station was open; his elbows rested on the ledge of it. The beefy man leaned against the red brick of the building. The argument between them went in circles like a droning bumblebee.

I sat on a wooden bench on the platform about ten feet away. I was a stranger in town, waiting for a train that was late. There was one other man present; he sat on the bench beside me, between me and the window. He was a tall, heavy man with a face like granite, an uncompromising kind of face, and huge, rough hands. He looked like a farmer in his town clothes.

I wasn’t interested in either the argument or the man beside me. I was wondering only how late that damned train would be.

I didn’t have my watch; it was being repaired in the city. And from where I sat I couldn’t see the clock inside the station. The tall man beside me was wearing a wristwatch and I asked him what time it was.

He didn’t answer.

You’ve got the picture, haven’t you? Four of us; three on the platform and the agent, leaning out of the window. The argument between the agent and the beefy man. On the bench, the silent man and I.

I got up off the bench and looked into the open door of the station. It was seven forty; the train was twelve minutes overdue. I sighed, and lighted a cigarette. I decided to stick my nose into the argument. It wasn’t any of my business, but I knew the answer and they didn’t.

“Pardon me for butting in,” I said, “but you’re not arguing about sound at all; you’re arguing semantics.”

I expected one of them to ask me what semantics was, but the station agent fooled me. He said: “That’s the study of words, isn’t it? In a way, you’re right, I guess.”

“All the way,” I insisted. “If you look up ‘sound’ in the dictionary, you’ll find two meanings listed. One of them is ‘the vibration of a medium, usually air, within a certain range,’ and the other is ‘the effect of such vibrations on the ear.’ That isn’t the exact wording, but the general idea. Now by one of those definitions, the sound — the vibration — exists whether there’s an ear around to hear it or not. By the other, the vibrations aren’t sound unless there is an ear to hear them. So you’re both right; it’s just a matter of which meaning you use for the word ‘sound.’ ”

The beefy man said: “Maybe you got something there.” He looked back at the agent. “Let’s call it a draw then, Joe. I got to get home. So long.”

He stepped down off the platform and went around the station.

I asked the agent: “Any report on the train?”

“Nope,” he said. He leaned a little farther out the window and looked to his right and I saw a clock in a steeple about a block away that I hadn’t noticed before. “Ought to be along soon though.”

He grinned at me. “Expert on sound, huh?”

“Well,” I said, “I wouldn’t say that. But I did happen to look it up in the dictionary. I know what it means.”

“Uh-huh. Well, let’s take that second definition and say sound is sound only if there’s an ear to hear it. A tree crashes in the forest and there’s only a deaf man there. Is there any sound?”

“I guess not,” I said. “Not if you consider sound as subjective. Not if it’s got to be heard.”

I happened to glance to my right, at the tall man who hadn’t answered my question about the time. He was still staring straight ahead. Lowering my voice a bit, I asked the station agent: “Is he deaf?”

“Him? Bill Meyers?” He chuckled; there was something odd in the sound of that chuckle. “Mister, nobody knows. That’s what I was going to ask you next. If that tree falls down and there’s a man near, but nobody knows if he’s deaf or not, is there any sound?”

Читать дальше