“Yeah, good,” Jocko said.

“Is that clock right?” Colley said. He was sitting alone in the back, and he leaned forward toward the front seat.

Jocko checked the dashboard clock against his wrist-watch. “I’ve got a quarter to,” he said.

“That’s what I’ve got,” Colley said.

“I never had a car in my life the clock worked,” Teddy said. “I stole Cadillacs, Mercedes-Benzes, Continentals, you name it. The clock never works.”

“They build them so they won’t work,” Jocko said.

“What do you mean?”

“They don’t want them to work.”

“Why wouldn’t they want them to work?” Teddy asked.

“If they wanted them to work, don’t you think they could build them so they worked? Man, they build a machine costs fifteen thousand dollars, whatever, everything all precision-made, you mean to tell me if they wanted that old clock to work, it wouldn’t work?”

“I guess they could make it work if they wanted to,” Teddy said.

“Sure,” Jocko said.

“Then why don’t they?”

“Who knows what their motive is?” Jocko said. “These big companies are all screwed up.” Abruptly, his voice and his manner changed. “Listen, I just want to go over this one more time, Teddy. After we come out, you’re going crosstown to Jerome Avenue, and we’ll ditch the car someplace near Yankee Stadium, wherever you find a good spot.”

“Yeah, I got it.”

“Then we go our separate ways, and meet tomorrow morning at my place.”

“Right,” Teddy said.

“Colley?”

“Fine.”

“You still worried?”

“No, no.”

“Just make believe it’s number fourteen. One after this will be fourteen, so just make believe it’s this one instead.”

“That don’t bother me no more,” Colley said.

“Or make believe it’s a baker’s dozen,” Teddy said.

“What’s that, a baker’s dozen?”

“That’s thirteen,” Teddy said.

“So how does that change anything? If a baker’s dozen is thirteen, I think of it as thirteen, it’s still thirteen, ain’t it?”

“Yeah, I guess so,” Teddy said.

“Jesus,” Colley said.

“Don’t think about it at all, ” Jocko said. “That’s the best way.”

“I’m not thinking about it,” Colley said. “I’m hot, that’s all. I can’t stand this kind of weather, that’s all.”

“Probably cool off later tonight,” Teddy said.

“Won’t cool off till we get some rain,” Colley said.

“Jeanine likes this kind of weather,” Jocko said. “She’s from Fort Myers originally — you ever been down that part of Florida?”

“I never been to Florida, period,” Colley said.

“Gets mighty hot down there in the summer. July and August, it’s a blast furnace down there.”

“Sounds like just the place for me,” Colley said.

“Yeah,” Jocko said, and laughed. “Jeanine loves it. A day like today, that’s a little too brisk for her.”

“Yeah, it sure is brisk,” Colley said.

“You want to take a right when we get to the corner,” Jocko said.

“Yeah,” Teddy said.

“Then it’s four blocks up.”

“Yeah.”

Jocko reached in under the blue poplin windbreaker he was wearing and pulled from the pocket of his trousers a Colt Cobra. The gun was almost identical to the Detective Special that Colley was carrying, except that it was partially made of aluminum and was lighter — fifteen ounces to twenty-one ounces for Colley’s gun. Both pistols were snub-nosed revolvers, with fixed sights and walnut stocks. Each gun carried six .38 Special cartridges. Jocko rolled out the cylinder now, idly glanced at the cartridges, nodded briefly, flipped the cylinder back into position, and put the gun in his pocket again. Teddy had made the turn onto the avenue now, and was heading north toward the liquor store.

Neither Colley nor Jocko had permits or licenses for the guns they were carrying; both guns had been purchased from receivers of stolen goods. If a cop stopped and searched them and found the pieces on them, they would both be charged with violation of Section 265.05 of the Penal Law — Possession of Weapons and Dangerous Instruments and Appliances. Colley practically knew the Penal Law by heart. Possession of a loaded firearm was a Class D Felony, punishable by a minimum of three and a maximum of seven. Teddy was driving very carefully. No one wanted the fuzz coming down on them for a bullshit gun violation. Get busted holding up a store, okay, that was a legitimate beef. But get stopped for passing a traffic light and then spend seven in jail on a gun rap — no way.

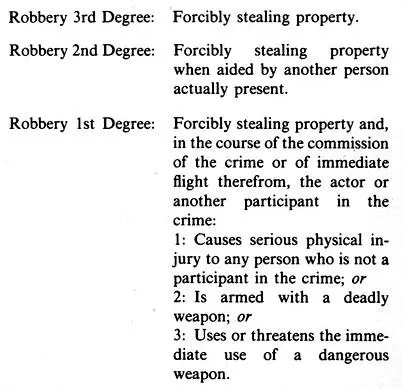

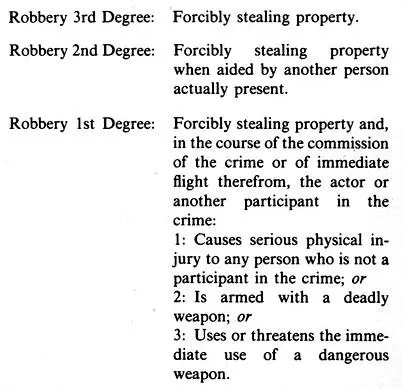

The Penal Law sections on robbery were very clear, with none of the fine print that existed in the burglary sections, where the degree of the crime was figured by whether the breaking and entry had been done in the daytime or in the night, in a dwelling or in a building, with a gun or without — man wanted to become a burglar, he first had to become a lawyer so he’d know what crime he was about to commit! But the robbery sections were in straightforward, almost blunt English, starting right off with the definition: Robbery Is Forceful Stealing. You couldn’t make it plainer than that. The various degrees of robbery were also plain to understand:

Any kind of robbery was a felony. For robbery three, you could get a maximum of seven years in prison; for robbery two, you could get fifteen; for robbery one, which was a Class B felony and nothing to sneeze at, you could get twenty-five. The three of them were about to commit, by definition, robbery one.

“There it is,” Jocko said. “Just up ahead.”

The crime itself began for them the moment Jocko said those words; until then there had been only the preparation for the crime. Until then the atmosphere had been relaxed and informal; now it became charged and tense. They had done this a dozen times before, and each time the risk was the same. Each time Colley and Teddy gambled whatever was in the cash register or safe against a possible twenty-five years in prison. Jocko gambled a possible life sentence; he had already taken two falls, another bust would be his third. He was twenty-seven years old and had already spent fourteen years of his life in detention centers, county jails, adolescent correctional facilities and hard-ass prisons. Colley had been sentenced to seven for the robbery-two fall, and had got out on parole after serving a little more than three. That had been shortly before last Christmas. He was twenty-eight at the time.

He had gone home to pick up his clothes and then had moved in with a girl he knew, a go-go dancer in one of the joints on Forty-ninth, just off Broadway. That had lasted about a week and a half, a total bummer. She kicked him out at the end of that time, called him a freeloader, said he wasn’t even any good in bed. He was living in a fleabag on Forty-seventh when he ran into Jocko in the bar that night. Only reason he’d sat down next to him was because he was hoping to make time with the black hooker. The next day he was holding a gun in his hand again. And two days after that, on Christmas Eve, he committed another robbery.

They knew just how to do it, they had done it together often enough and they expected to do it exactly the same way tonight. There was something athletic about their performance — an end running wide, perhaps, to receive a quarterback’s pass, a guard taking out the sole opposing tackle; or a smooth double-play combination, Tinkers to Evers to Chance — Teddy swiftly pulling the stolen automobile in toward the curb and cutting the engine, Jocko and Colley getting out on the curb side and beginning to walk purpose fully but not too swiftly toward the front door of the liquor store. There was something theatrical in their performance as well — Teddy looking bored at the wheel of the car as he lit a cigarette and let out a long stream of smoke, Colley and Jocko making small talk as they approached the store, some bullshit about Jeanine’s mother having come down with a summer cold, those were the worst kind, each of them responding to every hem and haw, every pause, every lifting of the eyebrow while robbery drummed in their heads, robbery hummed in their blood, robbery propelled them to the front of the liquor store.

Читать дальше