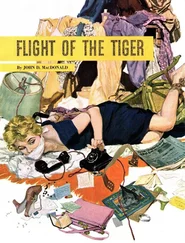

When the phone call came, a little after noon that Saturday, Crissy was on her back on a sun pad beside the sailboat tethered in the boat basin below her house. She had folded and tucked her bikini to the smallest possible dimensions, and she held her face upturned, the sun glowing oven-red through her eyelids, her face and body oiled, trickles of sweat diluting the oil. Francisca came pattering down the stone steps to say a newspaper was on the telephone.

It was a call she had expected, and to give herself time to go over probable questions and answers, she told Francisca to tell the man to phone back in twenty minutes. When he called again she had showered and just gotten into a robe. She took it on the bedroom extension, stretching diagonally across the large low bed, prone, propped on her elbows.

“Weldon, on the Record , Miz Harkinson. This Captain Garry Staniker, have I got it right that he worked for you?”

“Yes, that’s right, Mr. Weldon.”

“And the name of your boat was the Odalisque. Right? What was the size of it?”

“Not very large. It was a thirty-four foot Hatteras. Why are you asking me this, please?”

“Well, I guess you know he’s been found and...”

“Yes. It must have been a terrible thing.”

“The reason for the questions, there’s going to be some kind of investigation, find out if it was his fault. What we’re doing is trying to get the jump on it, trace him back a ways, see if people he worked for thought he was a good captain. How long did he work for you?”

“I guess you could say two and a half years, approximately. Nearer three. A little less than a year ago I put the boat on the market. I wasn’t using it very much, and the expense of the insurance and maintenance and dockage and fuel and the captain’s salary was just too much. When I put it on the market last April I paid him through May. I gave him excellent recommendations, but I guess jobs like that aren’t easy to find. Anyway, I kept reducing my asking price until the boat was sold last January. I got about half what I expected.”

“How did you happen to hire Staniker?”

“Actually a friend found him for me. The Captain had been operating a boat for a company my friend had an interest in, and they had decided to sell the boat.”

“Do you mind telling me who this friend was?”

“If I don’t tell you, I suppose you could find out easily enough. It was State Senator Ferris Fontaine. I’m afraid if you print this people might misinterpret it. I had an arrangement with the Senator whereby he had the use of the Odalisque and her captain whenever he wanted, letting me know in advance, of course. And he contributed to the upkeep. That’s why, a few months after the Senator passed away, I decided the Odalisque was costing too much for the number of times I was using it.”

“Were you satisfied with the job Staniker did?”

“Oh yes. He kept her in very good condition, ready to go on a moment’s notice.”

“Did he ever get into trouble with the boat?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, damage it in any way while running it.”

“There was just one little insurance claim. He went aground with the Senator and a party aboard up near Stuart, coming out of the St. Lucie Canal and heading out through the pass into the Atlantic. But I understand that is very tricky water up there, and the sand bars keep shifting. He ran aground at slow speed right in the Channel and bent a shaft and a wheel.”

“Did he drink while running your boat?”

“Sometimes when we went deep sea fishing and it was very hot, he’d drink some cans of cold beer. Nothing more than that as far as I know.”

“How about safety precautions?”

“The Odalisque was powered by gasoline engines, and he was always very careful about gassing up, always opening the hatches and turning on the blowers and being very firm with anybody who forgot and took out a cigarette. And he had a bilge sniffer installed when I first got the boat, with a warning buzzer. We passed the Coast Guard inspections without any trouble.”

“Then you were perfectly willing to give him a good recommendation when he was looking for another position?”

“Yes indeed. I gave him a letter, to whom it may concern, when he went on half pay, saying he had worked for me for such and such a period of time, and I was selling my boat, and I would be happy to answer any questions any prospective employer cared to ask about him.”

“Did many ask?”

“I think there were six or seven. I praised Captain Staniker to the skies, but I guess the jobs just never materialized. When I had to put him on half pay, Mrs. Staniker found a job at a little marina to make ends meet.”

“Did you keep track of how he was making out after your cruiser was sold, Mrs. Harkinson?”

After a careful moment of hesitation, she said, “I would say that I was kept better informed than I cared to be, Mr. Weldon. When he couldn’t find anything and began to lose his confidence, he seemed to begin to feel that I had some sort of responsibility to find him something better than working in that little boat-rental place. So he would stop by and tell me his problems. I felt too sorry for him to tell him to stop bothering me.”

“Did Mr. Kayd check with you before hiring him?”

“No, he didn’t. But I believe that Mr. Kayd was a friend of the Senator, and I think they had some mutual business interests. I didn’t know Mr. Kayd personally, but there is certainly a good chance he could have gone cruising on the Odalisque with one of the groups Senator Fontaine would take out, and he certainly could have talked to Garry Staniker and liked him, and found out that Garry ran a charter ketch all over the Bahamas for five years. And he would realize that Senator Fontaine would not — well, I guess you know the facts of political life, Mr. Weldon.”

“I see what you mean, sure. A boat is a good place to have a quiet little conference. Fontaine would have known Staniker was loyal and discreet when he recommended you take him on, and known he was competent. That should have been good enough for Kayd. Did Staniker tell you he’d landed a job?”

“He called up to tell me. He was very pleased and excited. He said it was a marvelous cruiser and fine people. But in the next breath he was complaining about it being a temporary job, perhaps six weeks, a little more or a little less. He said his wife was worried about giving up their job of operating the marina to take a temporary job, and he said that even though it was very good pay, maybe she was right. I told him that he should do the most marvelous job he could, and there was the chance Mr. Kayd might keep them on permanently, and without any children to tie them down, there was no reason they couldn’t take the Muñeca back to Texas. And even if Mr. Kayd didn’t want a permanent couple aboard, certainly he might recommend them to some of his Texas friends with yachts. It seemed to cheer him up. Frankly, it was a relief to me to know he’d found something, and he wouldn’t be heckling me for a while.”

“You read the story of what Staniker told those people, about the way it happened. You seem to know boats pretty well.”

“Not really. I only had that one cruiser, and I don’t think I’d want another one. They’re too much expense and responsibility. I’ve been learning to sail lately, and loving it.”

“When you read that account, Mrs. Harkinson, did you feel Staniker had maybe pulled a bad goof?”

“Not at all. It’s sort of natural to turn things on when you’re running. Blowers and bilge pumps and so on. And with that boat being diesel powered, and with a switch up on the fly bridge to turn on the generator and bring the other bank of batteries up, I’d think it would be a normal thing for anyone to just switch the generator on. A good captain tries to make everything as comfortable as he can for the owner and the passengers, so he would be thinking of the noise the generator would make if he had to run it at an anchorage after he’d set the hooks. Cruisers are very complex things, and there’s an old saying that no single thing ever goes wrong. It’s always three things going wrong at the same time. Things go wrong that you can’t anticipate. Like when the Sea Room blew up last year.”

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)