In this strangeness he always wanted to ask: What are they making me do? Why are they making me be like this? In the bright busy area things moved too swiftly for him to see them, but there were faces and places, books and buildings, words spoken too quickly to be understood. As always before it faded away, leaving him back in his own place, the memory of how it felt fading as quickly as the sensation, but knowing he would recognize it at once when it happened again, the way you recognize a dream you’ve had before.

He went over to the wall where he put the girls. Each month after he cashed his check, he would buy that magazine. And when it was a girl he thought would be nice to be with, a lively girl with a lot of fun in her, then he would cut out the folded page, print her name in the corner so he would not forget it, tack her onto the wall and introduce her to the others. Doreen, Ceil, Jackie, Puss, Bernadette, Connie, Judy Jean, Charleen. And they all smiled right at him, every one. The earlier ones were mottled by the dampness, the colors bleaching out of them.

Slowly and methodically he tore them free, making a neat packet, leaving a few corners tacked to the plywood. He held the stack in position to rip it in two, but could not because it suddenly seemed like tearing through all the tenderness of flesh. He folded the pictures, pondered in what box they might belong, put them in the box with his go-to-the-bank clothes.

Squatting there, he looked at the girl and said, “Too much light on your face, missy. Must have wore you out with all the aid station work. What the corpsmen used to say, don’t go moving them around too much. Do what you got to do right where they fall. You’ll know soon if they can stand moving, or’ll turn dead.”

He moved the lantern away from her, and in doing so momentarily put more light on her face, and was made uneasy by the immobility of it, a look of the skull. He set the lantern down, put his fingertips under the shelf of the jaw, felt nothing.

“So you died on me!” he yelled. “All I done for you! Hard as I worked, you damn little bitch! Just what the hell is the Lieutenant going to say? Missy, why’d you do such a fool thing?”

Her mouth seemed to move. He stopped, bent, peered, laid his two long fingers against her throat again.

“Now why should Corpo be cussing you out? There’s that little heart going along nice. Tump, tump, tump. Just put his fool fingers wrong and missed it, because it isn’t real hard and strong, but anyway it don’t have that bird-wing feeling any more, that fluttery stuff. Missy, you sleep deep and sweet, and Corpo’s going to be close by.”

He blew out the lanterns, waited for his night vision, then went out, crossed the little clearing, climbed the ladder to the driftwood platform he had built in the highest branches of the only live oak on the island, a water oak impervious to the salt water into which it thrust its roots.

Corpo sat crosslegged, looking out over the interwoven crown of the dense mangroves. From there, off to his right, he could see the blinkings of the range lights along the Waterway, see the light on the sea buoy out there beyond the Inlet channel, see the clutter of neon of the resort lights over on the beach side. To his left were the lights of the houses that ringed the bay, and back over his left shoulder were the city lights of Broward Beach. The night breeze was freshening out of the northeast. One of the nocturnal waterbirds flapped across the island, and made a sound like hoarse drunken laughter. He heard a rat-rustle in the cabbage palms, then a great surge and slap of a large fish just outside his channel, and the rushing sound of the smaller fish it had startled into flight. When the breeze would die, the marsh mosquitoes would cloud whining around him. He opened the wooden box he had nailed to the platform, took out the small bottle of oily repellent, greased his arms, neck and ears, annoyed at the odor of it which masked the night smells. Shortly after moving to the island he had stopped smoking, and the smells had come back until they were as strong as when he was a kid, able to find where the swamp cats slept, where owls had fed, where the swamp rattlers were nesting. This wind was a good one for the night smells. From other directions too often it had the smell of the meat they burned behind their candy houses, or the swollen stink of the city buses, or a smell from the dump fires beyond the city, a smell that to him seemed to have a color — a thin sulfurous green-yellow. Burned meat smelled purple. Bus stink was red-brown.

When he went down the ladder, yawningly ready for bed, as he crossed the clearing, he was startled to see the big pale shape of a strange boat under the porch platform, and after a puzzled moment, it all came tumbling back into his head. He hurried up the steps and into the cabin, knelt on the floor beside the bed in darkness, leaned his ear near her lips, felt and heard the weak but steady exhalations. Her breath was sour, and, through the sharper odors of the medication, he could scent the smell of sickness, a smell like fresh bread. He put the backs of his fingers against her forehead. The heat still came from it, and maybe it was a little less, but he could not be certain.

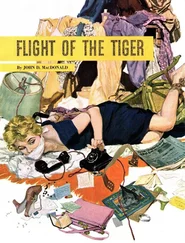

Suddenly he realized he could sleep on missy’s boat, in one of the two forward bunks. All day, and he hadn’t given that boat a real good look. It could have some good things on it, in a lot better shape than if it had gone down and they’d come washing onto the beach.

Once he was aboard he remembered seeing the flashlight in the same stowage locker where he had found the first-aid kit. He found it by touch, a good chunky one with a big lens, a red flasher, and one of those square six-volt batteries.

He found a lot of good things. Masks, fins, snorkels, spear guns, spinning rods, tackle box, nylon dock lines, fenders, charts, boat hook, bedding, several bottles of liquor, towels, bathing suits, hats, boat shoes, fire extinguisher, cans of engine oil. And, carefully wrapped against dampness, two guns. A twenty-two caliber target pistol and, broken down, a four ten gauge, single-barrel, automatic shotgun. Fool guns, he thought. Play toys. No punch at all to knock them down if they’re coming on you fast. He admired how neatly everything was stowed, and how the stowage compartments were fitted in.

Come daylight, he would figure out the electrical system and how much fuel she had, and how the little toilet worked. He opened the foredeck hatch for ventilation and figured out how the screens worked. He decided he would not use the bedding, just sleep on top of the plastic bunk cover. Crouched double under the low overhead, he stripped down to his ragged underwear shorts, turned the flashlight off and stretched out.

Immediately he began worrying about her. He went up and looked at her, came down and went back up again. Finally he tied a piece of cord around her ankle, ran it over to the trap door, let it hang through, and to the dangling end tied two empty tin cans, then dropped some small sinkers into them. When he tweaked the cord they made a splendid clatter. If she worsened, she might thrash around some, and if she woke up, it would give him warning so he could get to her before she got too scared waking up in a strange place.

The Lieutenant would be proud to know how well his sergeant was handling things. Saving everybody trouble. Why, if he ran that sick little girl over to town, they’d start yelling at him and get him all mixed up. And then all the candy fools in their candy houses would be signing up papers again, making trouble for the Lieutenant. And the Lieutenant had said not to get mixed up in anything at all, because give them half a reason they’d move him off the island for good. The Lieutenant would understand he couldn’t have just looked into that fine boat and seen her and then shoved the boat away to float on off into the mist. It was a poor damned excuse for a soldier didn’t look out for the wounded.

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)