“I’m getting you out of here,” I said, and took her by the hand, as Seth said, “I’ll always love you, Louise,” and a big black pistol came out from behind his back and blew a hole through her.

She swung in my arm like a rag doll, flung back by the impact. It pulled me down with her, my ears ringing from the gunshot; hit my head on the edge of a bench.

I wasn’t out long but when I looked up Seth hovered over me, and her; I didn’t have my gun, but I’m not sure I’d have had the presence of mind to use it if I had.

No matter. I looked up and Seth receded above me, his legs miles long, his head a tiny thing he was pointing the gun at, an old Army .45 revolver it must’ve been, and the muzzle flashed orange and my ears rang and his tiny head came apart in a red burst; then he fell like a tree, away from us, leaving a scarlet mist in the air where he’d stood.

I heard screaming. Not Louise’s. She had a blossom of red below the white collar of her new yellow dress, and lay silent, staring. It was the mother under the nearby tree doing the screaming, on her feet now, holding her little boy to her, shielding her little boy from the sight, but not able to keep her own eyes off it. The terrier was yapping.

I was just sitting there, spattered with their blood, the dead girl’s hand in mine.

Just sitting right there beside her for a long time, looking at her. Her eyes staring up at the sky. Her eyes. As big and brown as ever; so wide-set you almost had to look at them one at a time. But they weren’t beautiful anymore. I didn’t want to dive in there anymore. She was no longer in them.

So I closed them for her.

3

Where the Bodies Are Buried

September 9, 1934

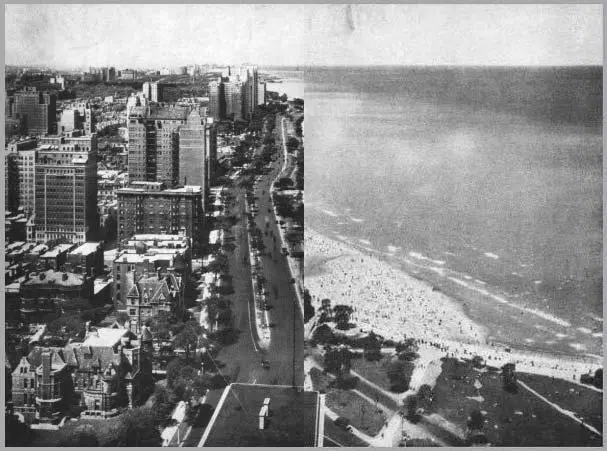

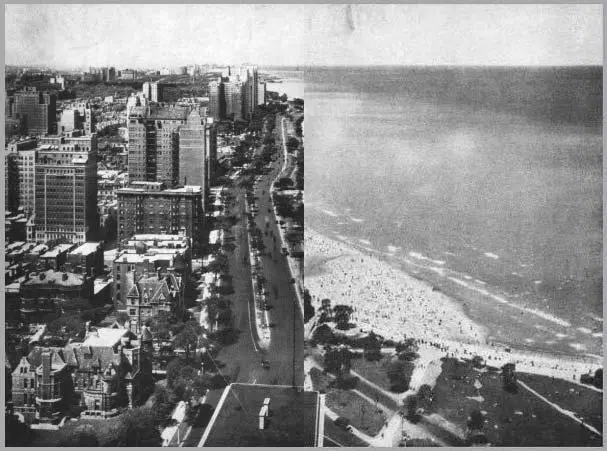

VIEW FROM SALLY RAND’S SUITE

When I got to her suite, she was standing in the doorway, leaning against the jamb in white lounging pajamas, a cigarette in one too-casual hand. Her light brown hair was marcelled, her mouth startlingly red, her eyes startlingly blue under those long, long lashes.

“Hi, stranger,” Sally said.

“Hello, Helen,” I said sheepishly.

“I was beginning to think you’d never call.”

“I wasn’t sure you’d want me to.”

She unstruck her pose and gestured with a red-nailed hand. “Come in and set a spell.”

“Thanks.” I took off my hat and went in, still feeling sheepish somehow. She closed the door behind me.

We sat on the sofa in her white living room; she kept her distance, but reached over and put her hand on my hand. I sat there looking ahead blankly. I couldn’t remember how to talk to her. I couldn’t remember how to talk to anybody.

“You look lousy,” she said.

“I feel lousy.”

“There could be a connection.”

I tried to smile; my lips couldn’t quite make it.

She said, “When’s the last time you slept?”

“I been sleeping a lot, really.”

“You mean you been passing out a lot.”

I swallowed. My mouth was dry, my tongue thick and furry. “You been talking to Barney?”

She nodded. “He’s got a fight to train for. You shouldn’t be distracting him like this.”

“Nobody asked him to.”

“To what? Sit with you while you drink yourself into a stupor? Carry you up the stairs and toss you in bed? Why’d you call me, Nate?”

Now I could find the smile; just barely, but it was there. “Barney talked me into it.”

She shook her head, smiled wryly. “You don’t deserve friends like us.”

“I know I don’t,” I said, and started to weep.

She had an arm around me. I was hunched forward cupping my hands over my face. She was offering me a handkerchief that she’d had in her hand, at the ready; she’d been talking to Barney, all right.

“Ain’t very dignified for a tough copper,” I said, swallowing snot. “I been on this crying jag for so long my goddamn eyes burn.”

“Is that why you’re drinking, Nate? Does the flow of booze stop the flow of tears?”

I grunted something like a laugh. “You don’t drink much, do you, Helen? Getting drunk is the one socially pardonable way a man can cry in public. Nobody blames a drunk for crying in his beer.”

“I hear you’ve been hitting something a little stronger.”

“Yeah. But not today. Today I’m stone-cold sober. And it scares hell out of me.”

She looped her arm in mine, moving closer. “Let’s go to bed.”

I shook my head, violently. “No! No. That won’t solve anything... that won’t solve anything.”

“We don’t have to do anything, Nate. We’ll just get under the sheets and be together. What do you say?”

“I’m so goddamn tired I’d fall asleep in a second.”

“That’s okay. What else is Sunday afternoon good for?”

The satin sheets felt good; for a moment it was like I’d never left this room. Like I’d been here with Sally forever. For a moment I felt like myself again.

For a moment.

“Did you love her, Nate?”

She really had talked to Barney; I’d spilled my guts to the little palooka, and he’d spilled his to her. Damn him. Bless him.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It was too rushed. She wasn’t... she wasn’t like you, Sally. She was just this dumb little farm girl.”

“I’m just an intelligent little farm girl, Nate.”

I found myself almost managing to smile again. “She was like you, a little. She could’ve been like you, if she’d had a break or two in her goddamn life. She wasn’t as smart as you, Helen. She wasn’t stupid, but she didn’t have your brains, your drive, your luck. You both found a way out, a way off of the farm. You just found a better way.”

“Did you love her, Nate?”

“I don’t know. It hadn’t got that far, really.”

“Did you sleep with her?”

I wondered how much Barney had told her.

“No,” I said.

She smiled like a wicked madonna. “You don’t lie worth a damn, Heller.”

Somebody laughed. Me?

I said, “It probably wouldn’t’ve lasted. But that isn’t the point. She was this sweet naïve thing who had a father who beat her and a husband who beat her some more. And then she fell in with... a bad crowd, and I came along, and she trusted me, and I killed her. I fucking killed her.”

She stroked my arm. “You didn’t kill anybody.”

“As good as. I took her right to the son of a bitch who did. For a thousand dollars.”

It had come in an envelope, with a bunch of stamps stuck on it, the Monday after. A fat envelope full of twenties. I’d hurled it against the wall, and the money spilled out like green confetti. Later, in one of my rare recent sober moments, I’d picked it up and stacked it and put it in a new envelope. It was in my bank deposit box, now. Money was money; it didn’t know where it came from. And even though I did know, I kept it. Out of perversity in a way. Because I had earned that money. Brother had I earned it.

“Why demand the impossible of yourself, Nate?” Sally asked. “There was no way you could have known that man wasn’t really her father.”

“I should have checked up on him. That’s twice lately somebody’s come in off the street and told me a story and I swallowed hook, line and sinker. I’m supposed to be a guy with some street savvy. Stick around — some guy’ll sell me the Wrigley Building, before the summer’s out.”

Smiling, she said, “You’re starting to sound like Nate Heller again, whether you like it or not.”

I sighed. “It’d be all right with me to come out of this. And I will. Being here’s a good sign.”

Читать дальше