Max Allan Collins

True Crime

For my son Nate

a real Heller

“Let’s do it.”

— Cole Porter

“Let’s do it.”

— Gary Gilmore

1

The Traveling Salesman

July 13, 1934 — July 23, 1934

CHICAGO, 1934

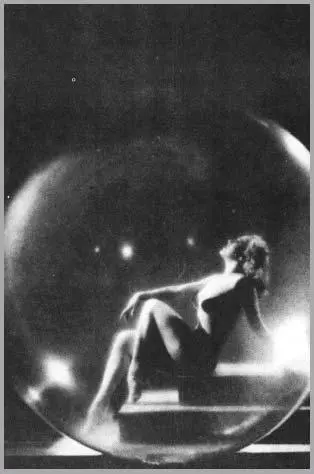

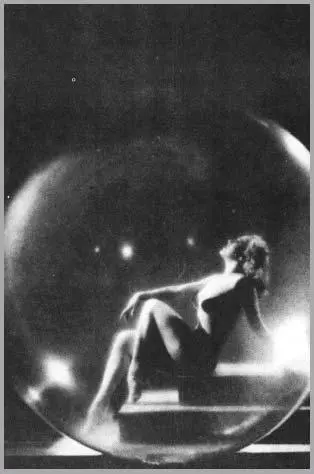

SALLY RAND AT THE WORLD’S FAIR

Somebody had to burst Sally Rand’s bubble.

And I was elected. I was, after all, the guy she’d hired to find out the truth about the self-professed oil millionaire from Oklahoma who’d proposed to her last Saturday night, after a month of flowers and gifts and nights on the town — though Christ knows where Sally found the time for the old boy, what with her various shows at the Paramount Club, the Chicago Theater and of course here at the Streets of Paris, at the world’s fair.

Sally had made the world’s fair, you see, or at least that’s what her press agent had led everybody but Chicago to believe. Story was the poor old Century of Progress Exhibition was a dismal flop till Sally dropped her pants and climbed behind her ostrich plumes, at which point the fair’s turnstiles began spinning like the city fathers in their graves.

Only that was a press agent’s dream; the fair was its own dream-come-true, and help from Sally Rand was appreciated, but hardly crucial. Chicago had watched through the fall, winter and spring as the art-deco spires rose from eighty-six acres along the lake, and by summer the city was eager to leave hard times temporarily behind to enter the City of Tomorrow. The turnstiles were spinning from the fair’s first morning, and Sally was only one of a small army of exotic dancers who helped fan the latter-day Chicago fire.

Because there was more than naked women to see at the fair. Like silk stockings being woven, and a Gutenberg Bible (and the press it had been printed on); like the Silver Streak streamliner; and an automobile assembly line; and something called television. You could even see a million dollars (at the Federal Building, under armed guard) or a million dollars worth of diamonds (at the General Exhibits building, similarly guarded). And kids of all ages could wonder at Sinclair Oil’s plaster dinosaurs, and the Seminole village where real, live Indians wrestled real, live alligators. And you could see Time and Fortune magazine covers two stories high, and a thermometer nineteen stories higher than that. You could see a lot more than just Sally Rand in the nude.

Not that there was anything wrong with seeing Sally Rand in the nude. I’d seen her show last year, the first year of the fair, and she by damn didn’t have anything on under there but her. The boys hadn’t been lying! And I understood this year she’d traded her plumes in for a big transparent balloon, a bubble she called it, and was nuder than ever.

I supposed most healthy male Chicagoans had made it out to Sally’s show during the opening week of the fair. But this was my first time this summer to the Century of Progress, though it had been open over a month already — because I’d had my fill of the place the summer before.

Like a lot of people in Chicago, for me the 1933 fair had meant work. Thousands of jobs had been created by the Dawes brothers — Rufus T., president of the fair, and his older brother General Charles G., former vice-president of the United States (under Coolidge), thought by many to be the real brains behind the Century of Progress. Say what you will about the Dawes brothers; dismiss them as businessmen/bankers whose efforts were self-serving, if you like. But they saw to it that a lot of dough got pumped into the Windy City.

Hotels were packed (and the hotels could use it — most of ’em were verging on bankruptcy before the fair) and restaurants and theaters did booming business, as did the newly reopened nightclubs and taverns (or at least newly openly reopened) after beer became legal in April of ’33, during the fair’s first summer. Prohibition gasped its last dry gasp (Repeal was only months away); and the Century of Progress — awash in beer as it was, thanks to the Capone/Nitti Outfit, who were willing to sell people suds even if it was legal — became a celebration of a better, wetter, tomorrow.

Of course, many — probably most — of the fairgoers were from out of town; and amid all those solid citizens from the farms and villages of the Midwest were pickpockets from everywhere else. And that’s where I came in.

Me. Nathan Heller. A private operative, but formerly a plainclothes dick on the pickpocket detail. Having that background, I’d been hired to coach the pith-helmeted private police force working the fairgrounds in the fine art of the dip. Or should I say, the fine art of spotting and nabbing the dip. And I’d done some supervising throughout the summer and fall, until the close of the fair in November. The job had paid a pretty penny.

I’d been hired by General Dawes himself, not because I was such a stalwart citizen, but because I had him over a barrel. That’s another story, which has been told elsewhere; for the purposes of this narrative, it’s enough to say that once General Dawes had repaid what he felt was a debt owed me, he saw fit not to hire me back when the Century of Progress was held over for a second year.

That, and a few other unpleasant experiences on these fairgrounds, had kept me away this summer, thus far. Now, as I strolled the fair on this sultry July afternoon, the walkway brimming with women in bright print dresses and floppy hats and men in shirt sleeves and straw boaters and kids in short pants and smiles, I felt a sense of nostalgia for the place, I’d spent time here with a woman I loved. Still loved.

But she was in Hollywood, both literally and figuratively, and I was in Chicago, underfed and underworked. Sally Rand was the first client I’d had in two months, outside of the ongoing work I did for a retail credit firm, checking credit ratings and investigating insurance claims. The A-1 Detective Agency (me) had had a good first year; unfortunately, it (I) was deep into its second year, and subsisting mostly on the dwindling proceeds of the first.

If Mr. Roosevelt was leading the country out of the Depression, he was starting somewhere other than Chicago — or anyway, somewhere other than the corner of Van Buren and Plymouth.

So now here I was again, feeling faintly ridiculous in my light-weight white suit and wide-brimmed Panama hat (souvenirs of a Florida job last year), wandering the avenues of the City of Tomorrow, in the shadow of the twin Eiffel-like towers of the fair’s famed Sky Ride, where “rocket cars” skimmed above the flat surfaces and pastel colors of the modernistic pavilions. One of the towers was nicknamed Amos, and the other Andy, but I never could remember which was which. (Except on the radio.) I hopped a double-decker bus, took a wicker seat on the upper open deck, where you could feel a lake breeze cut through the heat; that felt good, but being here at the fair again felt odd. It was like I was my own ghost, somehow; haunting myself. I got off at the Streets of Paris, which you entered through a big blue-and-white-and-red facade designed to look like a steamship.

Inside, the narrow “streets” were patrolled by phony gendarmes, a temporary world of sidewalk cafés with striped awnings and little round tables under big colorful umbrellas, and stalls where you could buy Parisian hats (by a North Side milliner) and charcoal sketches of yourself (by a Tower Town art student in a beret and paste-on mustache), along walkways prowled by chestnut vendors, strolling troubadors and flower girls. (No wildly careening taxicabs or whores, however.) The flat surfaces of flimsy exterior walls were covered with startling bright posters, and an outdoor “Lido” swimming pool boasted free floor shows of bathing beauties every bit as lovely as Miss Rand.

Читать дальше