“Louise, honey. Can I be serious for a second?”

She shrugged. “Sure.”

“You said this morning you couldn’t have kids. You’re a young woman. Are you sure about that? Have you checked with a doctor, or...?”

She tried to be nonchalant, puffed her cigarette. She definitely wasn’t inhaling. She said, “A doctor made me this way. Candy knocked me up one time, and the doc that took care of it didn’t do me right.”

Next door, Baby Face Nelson’s wife was moaning.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

She shrugged facially. “A real doctor looked at me later. He told me I couldn’t have kids. It’s okay. I don’t think I want kids anyways. They’re just a bother.”

The bedsprings sang next door; Nelson’s wife said, “Les! Les!”

I hugged the girl to me. “Don’t you worry about anything,” I said. “Everything’s going to be okay.”

She looked at me; the big brown eyes were wet. “Really?”

“I promise.”

She hugged me. Hard. Desperately hard.

Silence next door.

A few minutes later somebody knocked and hollered, “Soup’s on!”

Nelson.

“Time to chow down, lovebirds! Ha ha ha.”

Behind the central cabin, in which Ben and the little woman and their two kids lived, was a little brick patio, surrounded by a stone wall about waist-high. A slatted brown-stained picnic table, large enough for a dozen or so people, was in the middle. At the left was one of those white swings that looked like an inverted wooden V with the top squared off, in which two people could sit facing each other. At the moment Baby Face and his wife Helen were doing that very thing. To the right was a brick barbecue oven, the lower part as tall as a man and wide as his reach, with two openings, wood burning in the bottom, smaller one, and iron grids in the larger arched opening above that, at which point it narrowed into a chimney. Ma, wearing her calico apron over one of her familiar floral tents, was poking at various halfed chickens spread out on the lower of two grills, basting them occasionally from a bowl of thin red sauce; a pot of baked beans was biding its time on the upper grid.

The picnic table began to fill up, and soon the whole gang — if you’ll pardon the expression — was having at the platters of barbecue chicken and the several bowls of coleslaw and the pot of baked beans; beers, Cokes, glasses of milk were scattered about, as were plenty of paper napkins. Baby Face Nelson and Helen, Pretty Boy Floyd, the Barker brothers and Fred’s girl Paula, Old Creepy Karpis and Dolores, chowing down like this was a family picnic. Speaking of family, Ben, the little woman and their two kids were down at one end of the table. The little woman had, in fact, made the slaw, which was very good, and had got the fire going earlier in the afternoon that had made the chicken possible. But that was the extent of her being sociable, and she wasn’t eating much, just picking at her paper plate.

Her kids would look down the table toward Nelson, who would wink at them, and the kids would grin at him, and each other. I’d seen this at the farm, too — Nelson got along famously with Verle and Mildred’s two boys, as well — and wondered if somehow I was seeing the real George Nelson. Or anyway, Lester Gillis.

His wife Helen picked up on the byplay between him and the kids, and said to him, “I miss our two.”

Nelson looked momentarily sad — the only time I ever saw sadness touch his face — and said, “We got to find a way to get to Mom’s and see ’em. We just got to.”

Louise whispered to me, “That’s sweet,” without sarcasm. I don’t think she and sarcasm were acquainted, actually.

Next to Nelson was a dark-haired, dark-eyed man, eating quietly, holding the messy chicken in his hands almost daintly, like the dead barbecued bird was a teacup. He was handsome, a lady-killer type, but on the cadaverous side, with a little Ronald Colman mustache, and even sitting down you could see he was tall, much taller than Nelson. This was John Paul Chase, Nelson’s dog-loyal sidekick, who’d been posted in the barn back at the Gillises’. I hadn’t seen him arrive, so he’d apparently come later in a car of his own.

He said, “Pass the salt, please.”

It was the only thing I ever heard him say.

Nelson would speak to him occasionally, and Chase would just nod. Nelson called him J.P. Using initials for nicknames was a trend Nelson was trying to set in these circles, with no apparent success.

There was no talk of crime at the table. The subjects at hand were baseball (did the St. Louis Cardinals, a.k.a. the “Gashouse Gang,” have the pennant sewn up or not?) and boxing (would Ross take McLarnin in their rematch next month?) and how good Ma’s cooking was (better ’n Betty Crocker’s).

Doc Barker, who’d taken little part in the small talk, did at one point say, “Where’s your friend Sullivan?”

Floyd, hands red with barbecue sauce, glanced above the half-eaten half a chicken he was eating (his second) and said, “He don’t feel so good. We tied one on last night.”

Fred Barker paused mid-chicken to grin, gold teeth flashing. “Hung over, huh?”

Floyd smiled; he had sauce all over his lips and teeth. “ Way over.”

Doc said, “Is he going to be up for it?”

“Sure,” Floyd said, matter-of-factly.

“I never worked with the guy.”

“I have,” Floyd said. Friendly but with a hard edge.

“I never even heard of him.”

Floyd put the chicken down. “I don’t work with just anybody, Doc.”

“I never said you did, Chock.”

Nelson, working on a bite of baked beans, said, “Yeah, why isn’t your pal Richetti in on this one? I thought he was your right-hand man.”

“He’s on the mend. Caught a bullet while back.”

“Sorry to hear it,” Nelson said. “Suppose he’s holed up in the Cookson Hills, huh?”

Floyd shook his head no. “We been havin’ to avoid the hills. Ever since the feds and the state militia did that sweep through there February last, we been stayin’ out.”

Karpis, who was sharing half a chicken with Dolores, said, “I heard they only nailed a dozen or so crooks, all of ’em small-timers, with that search party.” Small laugh. “A thousand men combing the hills for small change.”

Floyd nodded. “Still, with the governor willin’ to turn up the heat that high, we been keeping out of there. We been holing up ’round Toledo way.”

Doc said, “Licavoli mob’s helping you out, I suppose.”

“Yeah,” Floyd said. “For a price.”

Doc sighed, nodded. “Yeah. This ol’ life ain’t cheap, is it?”

“Life’s cheap enough,” Floyd said. “It’s livin’ that gets expensive.”

Louise, who was an even daintier eater than John Paul Chase (she was the only one at the table cutting the meat off the chicken with her knife and fork, instead of just using her hands — her daddy must’ve beat some manners in her), had finished her meal and was starting to complain of getting eaten up by mosquitoes. The sun was going down and the bugs were coming out.

Floyd stood. “You nice gals can clear the table, if you would, and get in away from the skeeters. Us men got work to do.”

Karpis wiped his face and hands with a napkin and stood as well. “Yes we do. Let’s go down to my cabin.”

The men went down to his cabin.

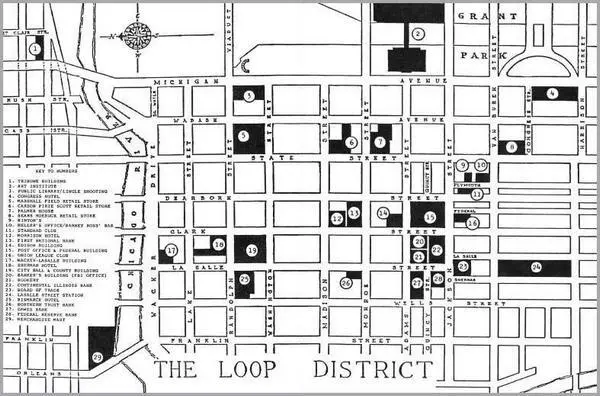

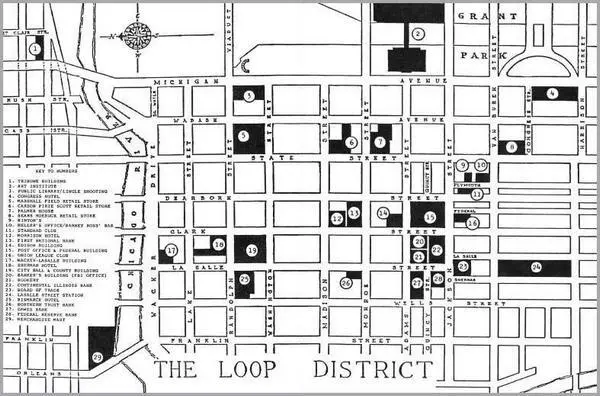

Karpis’ cabin was identical to ours, except with the beds on the opposite side of the room. In addition he’d had some folding chairs brought in. Everybody found chairs or sat on the edge of one of the beds, which was where I ended up, over to the far left, by the wall, facing Karpis, who, looking more and more like a schoolteacher, stood by the facing wall where he’d tacked a big homemade grease-pencil map of the Chicago Loop.

Читать дальше