A hand on my shoulder pulled me back. It belonged to Zarkovich.

“Get away from there, Heller!”

Another hand from behind me yanked me into the alley. People were coming down the alley toward the body; their feet clomped, echoing on the cobblestones.

But two others were running down that alley, away from the scene, hand in hand, like schoolgirls.

Anna and Polly.

I walked back toward the gathering crowd. This was Dillinger , they said; they got Dillinger. Women were kneeling, dipping their hankies and even the hems of their skirts into the pool of the man’s blood. Souvenir hunters.

Then Purvis was in their midst; he was angry.

“Get away!” he said. “Get away!”

They scrambled away, like rats in dresses, clutching their bloody booty. Purvis had frightened them, because he had a gun in his hand, and his coat was open, the buttons torn away when he reached for the revolver, going after Dillinger. But he hadn’t fired the gun.

Zarkovich and O’Neill had done all the shooting.

Cowley appeared from somewhere and was directing his men to cordon the body off.

“Keep these damn ghouls away!” Cowley ordered.

I approached the body again and looked down at it. Purvis and Cowley were there with me. They glanced at each other, then looked at me. They actually seemed embarrassed.

“I wanted to take him alive,” Purvis said, “but he pulled a gun.”

Cowley nodded, pointed down to the gun in the corpse’s slack hand. “You can see it right there.”

Purvis knelt over the body; with both him and the dead man wearing straw hats, Purvis seemed to be looking down at a ghastly mirror image. “It’s Dillinger, all right. No doubt about it. But it’s amazing the extent of plastic surgery he underwent. All the distinguishing marks on his features have been worked over. It was a good job the surgeon did.”

“Check his pockets,” Cowley said.

Purvis did. He found $7.80 and a gold watch.

Purvis held out the $7.80 in the palm of one hand, and said, “So much for the fruit of crime.”

Cowley took the watch; popped it open. There was a picture inside. He showed it to Purvis.

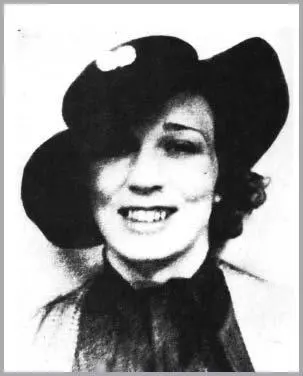

Purvis said, “That’s Dillinger’s old sweetie, Evelyn Frechette. No doubt about it.”

Cowley nodded.

I took a look at it. The picture was of Polly Hamilton. I didn’t say anything.

A couple of Chicago uniform cops, in blue shirts with badges pinned on, pushed through the crowd.

“So this is John Dillinger,” one of them said, looking down at the corpse.

Purvis said, “Yes it is. Uh... what do we do now?”

The two cops looked at each other. Then they looked at Purvis.

“Who’s in charge here?” one of the cops asked.

“I am,” Purvis and Cowley said.

The Chicago cops shook their heads and one of them said, “I’ll call a meat wagon.”

In minutes it was there, and the dead man was put on a stretcher and slung in back of the wagon; Purvis rode with him, with several other feds. Cowley stayed behind. The crowd remained thick. I pushed through toward my parked Chevy.

In the midst of the crowd, by the tavern, I bumped up against a big guy in a fedora. The tavern’s neon turned his face orange. He had a bandage across his nose. I gave him the hardest kidney punch I could muster.

“Oooofff,” he said, and hit the pavement. People were walking on him.

I kicked him in the ribs, while he was down there, and another East Chicago cop, a guy with a puffy face — courtesy Barney Ross — came pushing through the crowd, having seen what I did, and he swung at me and hit some woman in the side of the head. A barrel-chested man with her, her husband I guess, said, “Hey!” And smacked the East Chicago cop in the face a couple of times.

The crowd was such that it didn’t go further than that — no fight ensued or anything; and I was to my coupe, with a small sense of satisfaction in having somewhat settled a score.

But as I pulled away from the Biograph theater, I felt sick to my stomach, and vaguely ashamed. I’d seen this happening, and I hadn’t been able to stop it. Maybe I wasn’t smart enough or brave enough or tough enough. I must’ve been lacking something.

Because a man had died tonight. A man I had, in a roundabout way at least, fingered.

I’d got my first good close-up look at Jimmy Lawrence tonight, when I’d held his dead head in my hands.

And he’d looked less like John Dillinger close up than at a distance.

But he had looked real dead.

POLLY — THE PHOTO IN THE WATCH

By a quarter till midnight, I was sitting at my desk in my office in the dark. Neon pulsed through the half-open windows in tempo with the rubber-hose aches and pains that had started in again, now that Sally’s last round of aspirins had worn off. I’d considered stopping in at Barney’s Cocktail Lounge for another sort of painkiller, but was in the sort of black mood that drinking would only turn blacker.

This was the first I’d been back to the office since I took that beating. Barney had cleaned the place up; everything was in order. What did I have to complain about? I had the world’s lightweight champ for a personal valet.

My mouth was trying to remember how to smile when the phone rang.

“Yeah?” I said.

“Nate?”

It was Sally.

“Hi, Helen.”

“I thought maybe you might’ve gone back to your office...”

“Where are you calling from? Didn’t you have a show tonight?”

“Yes — I’m calling from backstage. I tried to get you at my suite, thinking you’d be back there by now... I did give you a key, didn’t I?”

“You did. I just didn’t think I’d be very good company the rest of the night.”

“I understand.”

“You do, Helen?”

“Yes.” A pause. “People are saying John Dillinger was shot.”

“Christ, word travels fast in this town.”

“It’s true, then.”

“Somebody was shot, yeah.”

“Were you there?”

“I was there. I saw it.”

She didn’t say anything right back, and I could hear the Café de la Paix orchestra playing “Whoopee” in the background, Paul Whiteman style.

Then: “I’m going to take a taxi home in about fifteen minutes, Nate. Why don’t you head over to the Drake and meet me?”

“I don’t think I better.”

“We could talk...”

“I don’t think I have any talk left.”

“I’d like to help.”

“If anybody could, it’s you. Tomorrow.”

Another pause; another bride, another groom...

“Tomorrow,” she said.

And hung up. Me too.

I sat in the dark a few minutes; the street sounds were subdued tonight, I was thinking — then the El rushed by. After that I got up to pull the Murphy bed down out of its box. I was reaching up to do that when there was a sharp insistent knock on the door — a three-beat tattoo. Then again.

There was just enough light out there in the hall for me to make out through the frosted glass the shape of the person knocking. It was a small person. Not two cops with a rubber hose.

I unlocked the door and peeked out.

“I’ll be damned,” I said.

She smiled nervously and long lashes fluttered over eyes as blue as Sally Rand’s. But this girl in a white blouse and tan skirt and open-toe sandals was not Sally Rand.

“Hello, Nate,” Polly Hamilton said.

“Hello.”

“Can I come in?”

“Okay, but I’m not going to the movies with you, so don’t bother asking.”

Her lower lip quivered and she glanced down. “You must think I got that coming.”

Читать дальше