“Well, uh, if somebody wanted Dillinger dead, why wouldn’t somebody just kill him? Why go to such elaborate lengths to have the feds do the job?”

Nitti’s mouth etched itself into an enigmatic little smile.

Then he said, “You’re operating here out of curiosity, Heller. Nothing else. No client. Just curiosity. And you know what happened to the goddamn cat.”

I knew.

“You played a part in this thing,” Nitti said. “Like I said, if I’d known they was planning to suck you in, I’d have stopped it. Only they did suck you in. Well, you played your role, now get offstage, go home. Stay out of it, and stay the hell out of the way.”

“What if Cowley or Stege or Purvis come around?”

“Why don’t you just report what you know to be true, and leave it go at that, in such event.”

“You mean, tell them about tailing Polly Hamilton and Jimmy Lawrence, and that Anna Sage says Lawrence is Dillinger.”

“Yeah. It starts and ends with that.”

“And I just stand by and let the poor shmuck get killed.”

He raised a finger in a cautionary fashion. “I’m not saying anybody’s going to get killed. But what skin off your ass is it if some fuckin’ Hoosier outlaw gets what he’s gonna get someday anyway?”

“Frank,” I said, “when I bitched about Cermak’s boys hitting you, the same argument was advanced. That Nitti was a guy who was going to meet a bullet one of these days anyway, so what the hell.”

He gestured with two open hands. “I’m a restaurant owner. Restaurant owners don’t get shot, not unless maybe some goddamn outlaw comes in and robs the till.”

“I don’t like being a part of this.”

“Good,” Nitti said. “Don’t be.” He reached in his right pants pocket and took out a money clip. The thickness of bills included a fifty on top, which he peeled off, then he peeled off another fifty. He smoothed them on the tablecloth before me; the two bills were spread out in front of me like supper. Like a six-course meal.

“I want to be your client,” Nitti said.

“You do?”

“Yeah, kid. That’s a hundred-dollar retainer. I want your services between now and Monday. I got something I want you to do for me till then.”

“What’s that, Frank?”

“Sleep,” he said. “Go home and sleep. Till Monday.”

I swallowed.

Then I took the money, because I didn’t dare not take it. Added it to the five and five ones on my own clip.

“This meeting between us, it never happened. Capeesh ?”

“ Capeesh ,” I said.

“This is hard for you, ain’t it, kid?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I like you. I really do.”

And he did. He cared about me. The way you like and care about a character in a radio serial you follow. But if a streetcar ran me over in tomorrow’s episode, he wouldn’t lose any sleep that night.

“Is it okay if I go now, Frank?”

“Sure, kid. You don’t have to ask my permission to do things. You’re your own man. That’s what I like about you. Now, go.”

I went.

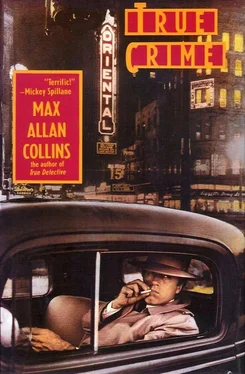

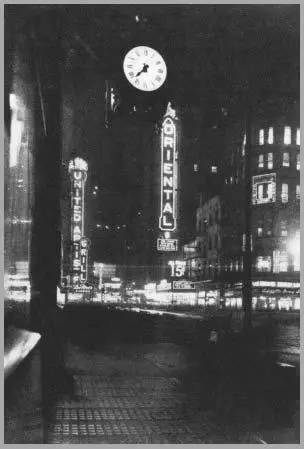

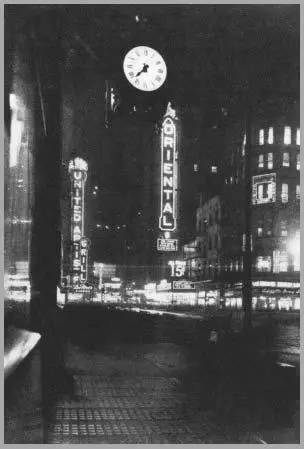

RANDOLPH AND STATE, DEARBORN, A BLOCK DOWN

At my office that afternoon I couldn’t resist checking one last thing out. Frank Nitti or no, there was something I had to follow through on. In the bottom of my pine four-drawer file I had several out-of-town phone books, as well as two Chicago cross-directories (numbers first; addresses first). I took out the Gary, Indiana, book and looked in the Yellow Pages. There were six grain companies. I called the personnel departments of each; it took all the rest of the afternoon, and talking to two or three people each place, which ran my phone bill up, but I did it. And John Howard didn’t work for any of them.

Not that I’d expected him to. It was obvious, now, that my traveling-salesman client was a con artist hired to rope me into the play Zarkovich and Nitti were putting on. I felt like a chump. And with good reason: I was a chump.

I took the money clip out of my pocket, peeled off the two fifties Nitti had given me. A braver man would’ve tossed them in Nitti’s face. He’d also be a dumber man, and possibly a deader one. Maybe if I had the integrity Nitti was talking about, I’d turn the bills into confetti and toss them out my office window; or give ’em to the first down-and-outer on the street I ran across. But I needed a new suit, so I went out and bought one. The rest of the money could go for luxuries. Like eating and the phone bill.

Some of Nitti’s money I decided to blow on Barney Ross and his girl Pearl. I called him over at the Morrison and he said he and Pearl were planning to go out for a bite, but had no special plans. So I drove over and picked ’em up and took Pearl and her smart green dress and Barney and his blue bow tie to my favorite restaurant in the city, Pete’s Steaks.

Pete’s was on Dearborn, just north of Randolph. Pretty redheaded Pearl, on Barney’s arm, tried to hide her surprise as we approached the place; the neon sign that hung above the awning had a few vowels burned out, so that it read P T ’S STE KS, and looking in the window all you could see was an ordinary white-tile, one-arm joint. But then we went inside, and back to the rear of the place and up the steps to the air-cooled dining room, where framed autographed celebrity photos (including one from Barney, signed to Bill and Marie Botham, the owners — I never did find out who Pete was) rode the walls of the long, narrow dining-car-like room.

As soon as Pearl started spotting celebrities (Eddie Cantor and George Jessel were at a table together and, at another, second time today, Rudy Vallee) she brightened. The place catered to the show biz crowd, press agents, song boosters, chorines, vaudevillians, with a good number of newspapermen tossed in in the bargain. Doc Dwyer of the Examiner , Hal Davis of the News , and Jim Doherty of the Trib were here tonight, and probably some others I didn’t recognize.

Our table conversation ran to small talk — Barney had taken Pearl to the fair today, including Sally Rand’s matinee, which Pearl found “shameless,” but sort of giggled when she said it — and I mostly just listened. But Barney was watching me close; he knew I was in a black mood. He also knew I’d called and invited him and Pearl out to try to shake that mood, and that I wasn’t being particularly successful.

The steaks arrived and helped distract me. Thick and tender and juicy, with melted butter and a side concoction of cottage fries, radishes, green onions, peas and sliced Bermuda onions that spilled onto the steak. I’d eaten nothing today except a bagel at the deli under my office, when I’d got back from Nitti’s; it’d been all I could make myself eat. But I was ravenous, now, and I attacked the rare steak like an enemy. Pearl, fortunately, didn’t notice my rotten table manners; she was too caught up in her own Pete’s Special. Barney, though, continued to eye me.

A minor sportswriter from the Times , whose name I didn’t remember, buttonholed Barney on the way out, and I stood and talked to Pearl at the top of the stairs.

“You’re a very special friend to Barney,” she said.

“He’s a special friend to me.”

“When you’re in Barney’s position, the friends you had before you got famous are the important ones, you know.”

“Are you going to marry him, Pearl?”

“If he asks me.”

“He will.”

She gave me a pretty smile, and I managed to give one back to her. A smile, that is. I doubt it was pretty.

Читать дальше