‘I guess,’ I agreed, ‘That I have.’

It would have been difficult not to, since the champion jockey was twice as popular as the Prime Minister and earned six times as much. His face appeared on half the billboards in Britain encouraging the populace to drink more milk and there was even a picture strip about him in a children’s comic. Everyone, but everyone, had heard of Colin Ross.

Kenny Bayst climbed in through the rear end door and sat in one of the two rear seats. I took a quick look round the outside of the aircraft, even though I’d done a thorough pre-flight check on it not an hour ago, before I left base. It was my first week, my fourth day, my third flight for Derrydown Sky Taxis, and after the way Fate had clobbered me in the past, I was taking no chances.

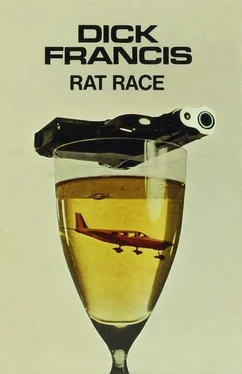

There were no nuts loose, no rivets missing on the sharp-nosed little six seater. There were eight quarts of oil where there should have been eight quarts of oil, there were no dead birds clogging up the air intakes to the engine, there were no punctures in the tyres, no cracks in the green or red glass over navigation lights, no chips in the propellor blades, no loose radio aerials. The pale blue cowling over the engine was securely clipped down, and the matching pale blue cowlings over the struts and wheels of the fixed undercarriage were as solid as rocks.

By the time I’d finished the other three passengers were coming across the grass. Goldenberg was doing the talking with steam still coming out of his ears, while the Major nodded agreement in unhappy little jerks and Annie Villars looked as if she wasn’t listening. When they arrived within earshot Goldenberg was saying ‘... can’t lay the horse unless we’re sure he’ll pull it...’ But he stopped with a snap when the Major gestured sharply in my direction. He need hardly have bothered. I had no curiosity about their affairs.

On the principle that in a light aircraft it is better to have the centre of gravity as far forward as possible, I asked Goldenberg to sit in front in the right-hand seat beside me, and put the Major and Anne Villars in the centre two seats, and left Kenny in the last two, with the empty one ready for Colin Ross. The four rear seats were reached by the port side door, but Goldenberg had to climb in by stepping up on the low wing on the starboard side and lowering into his seat through the forward door. He waited while I got in before him and moved over to my side, then squeezed his bulk in through the door and settled heavily into his seat.

They were all old hands at air taxis: they had their safety belts fastened before I did mine, and when I looked round to check that they were ready to go, the Major was already deep in the Sporting Life . Kenny Bayst was cleaning his nails with fierce little jabs, relieving his frustration by hurting himself.

I got clearance from the Tower and lifted the little aeroplane away for the twenty mile hop across Berkshire. Taxi flying was a lot different from the airlines, and finding racecourses looked more difficult to me than being radar vectored into Heathrow. I’d never before flown a racecourse trip, and I’d asked my predecessor Larry about it that morning when he’d come into the office to collect his cards.

‘Newbury’s a cinch,’ he said offhandedly. ‘Just point its nose at that vast runway the Yanks built at Greenham Common. You can practically see it from Scotland. The racecourse is just north of it, and the landing strip is parallel with the white rails of the finishing straight. You can’t miss it. Good long strip. No problems. As for Haydock, it’s just where the M6 motorway crosses the East Lanes road. Piece of cake.’

He took himself off to Turkey, stopping on one foot at the doorway for some parting advice. ‘You’ll have to practise short landings before you go to Bath; and avoid Yarmouth in a heatwave. It’s all yours now, mate, and the best of British Luck.’

It was true that you could see Greenham Common from a long way off, but on a fine day it would anyway have been difficult to lose the way from White Waltham to Newbury: the main railway line to Exeter ran more or less straight from one to the other. My passengers had all flown into Newbury before, and the Major helpfully told me to look out for the electric cables strung across the approach. We landed respectably on the newly mown grass and taxied along the strip towards the grandstand end, braking to a stop just before the boundary fence.

Colin Ross wasn’t there.

I shut down the engine, and in the sudden silence Anne Villars remarked, ‘He’s bound to be late. He said he was riding work for Bob Smith, and Bob’s never on time getting his horses out.’

The other three nodded vaguely but they were still not on ordinarily chatty terms with each other, and after about five minutes of heavy silence I asked Goldenberg to let me out to stretch my legs. He grunted and mumbled at having to climb out onto the wing to let me past him and I gathered I was breaking Derrydown’s number one rule: never annoy the customers, you’re going to need them again.

Once I was out of their company, however, they did start talking. I walked round to the front of the aircraft and leant against the leading edge of the wing, and looked up at the scattered clouds in the blue-grey sky and thought unprofitably about this and that. Behind me their voices rose acrimoniously, and when they opened the door wide to get some air, scraps of what they were saying floated across.

‘... simply asking for a dope test.’ Anne Villars.

‘... if you can’t ride a losing race better than last time... find someone else.’ Goldenberg.

‘... very difficult position...’ Major Tyderman.

A short sharp snap from Kenny, and Anne Villars’ exasperated exclamation. ‘Bayst!’

‘... not paying you more than last time.’ The Major, very emphatically.

Indistinct protest from Kenny, and a violently clear reaction from Goldenberg: ‘Bugger your licence.’

Kenny my lad, I thought remotely, if you don’t watch out you’ll end up like me, still with a licence but with not much else.

A Ford-of-all-work rolled down the road past the grandstands, came through the gate in the boundary fence, and bounced over the turf towards the aircraft. It stopped about twenty feet away, and two men climbed out. The larger, who had been driving, went round to the back and pulled out a brown canvas and leather overnight grip. The smaller one walked on over the grass. I took my weight off the wing and stood up. He stopped a few paces away, waiting for the larger man to catch up. He was dressed in faded blue jeans and a whitish cotton sweater with navy blue edgings. Black canvas shoes on his narrow feet. He had nondescript brownish hair over an exceptionally broad forehead, a short straight nose, and a delicate feminine looking chin. All his bones were fine and his waist and hips would have been the despair of Victorian maidens. Yet there was something unmistakably masculine about him: and more than that, he was mature. He looked at me with the small still smile behind the eyes which is the hallmark of those who know what life is really about His soul was old. He was twenty six.

‘Good morning,’ I said.

He held out his hand, and I shook it. His clasp was cool, firm, and brief.

‘No Larry?’ he enquired.

‘He’s left. I’m Matt Shore.’

‘Fine,’ he said noncommitally. He didn’t introduce himself. He knew there was no need. I wondered what it was like to be in that position. It hadn’t affected Colin Ross. He had none of the ‘I am’ aura which often clings around the notably successful, and from the extreme understatement of his clothes I gathered that he avoided it consciously.

‘We’re late, I’m afraid,’ he said. ‘Have to bend the throttle.’

Читать дальше