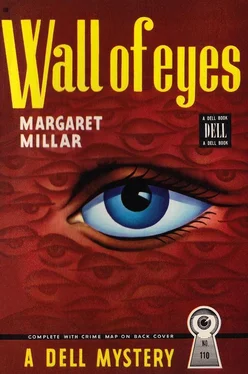

Margaret Millar

Wall of Eyes

To My Aunt

ALICE FERRIER GOULD

They moved briskly along the street, the girl carefully indifferent to the stares of the people who passed, the dog unaware of them. He padded along looking neither to the left nor right, his eyes careless and shifty. But when he came to a hole in the sidewalk he guided Alice around it and she felt the firm gentle tug of his harness and followed him.

I wonder if he knows I’m not blind, Alice thought.

He paused at the corner and ran his eye casually over the traffic. Then he stepped off the curb and Alice stepped off too, smiling a little. He’s very conscientious, she thought, he’s doing his duty but he doesn’t have to like it.

When they were across the street she leaned over and put her free hand on his head for an instant.

“Good dog. Good Prince.”

He was bored with the compliment. He turned his head away with a stem there’s-a-place-for-everything movement and continued to walk, picking his way among the fallen leaves.

They were still on St. George Street, but the street itself was changing. They had passed the section of crumbling grandeur, of decayed castles with “Rooms for Rent” signs hammered on sagging pillars and listing porches. This part of the street alternated quaint tea rooms with filling stations and fraternity houses.

She slowed her step and began peering at the numbers of the houses. A young man in a gray topcoat was coming toward her. When he saw the dog he stopped and said, “Could I help?”

The dog didn’t even look at him but sank onto the sidewalk with his head between his paws.

Alice turned and saw that the young man had a wet leaf plastered to his hair. She tried to make her eyes blank, like Kelsey’s, to avoid embarrassing him.

“Yes, thank you,” she said. “I’m looking for Dr. Loring’s house.”

He looked at her curiously, shyly, as one looks at a cripple. Even though he thinks I’m blind, Alice thought, he is too polite to stare.

“Next house up,” he said. “May I help you there?”

“No, thanks,” Alice said. “Prince and I will find it.”

Prince was already on his feet, sensing the call of duty, feeling the subtle movement of her hand on his harness. They walked on. Alice wanted to turn around to see if the young man was looking back but she kept her eyes on Prince, still smiling. The young man had delighted her, he was so earnest and so completely unaware of the wet leaf clinging rakishly to his hair.

But with the elation there was the old feeling of strangeness, loneliness, because it was such a silly, sly thing to find pleasure in.

The house was old but the lawn was freshly raked and the sign, “Dr. T. Loring,” gleamed like a small brass sun. On the veranda there was another sign, “Ring and Walk In.” She rang the bell and opened the door with the brisk precise movements of one who feels she is being watched from behind curtains and wants to impress the watcher.

There was no one else in the office. She had been afraid that there would be someone, but now that there wasn’t she felt no relief. The fear was still there, but it had divided like an amoeba, and the two new parts were full-grown, self-sufficient, able to slide through her veins and divide again and again. Fear of Kelsey, of scandal, of the doctor, of her own security, fear of being wrong.

And perhaps he wasn’t a good doctor — she refused to think of him yet as a psychiatrist, refused to let her mind or mouth form the word — or perhaps most of his patients were too bad to come to his office, like the cretin she had seen years ago, a gibbering, drooling, fat-tongued boy who had stroked her damp hand with his hot, dry one.

Prince was lying on the floor beside her feet, not in the easy relaxed manner of ordinary dogs, but watchfully, his eyes moving in their sockets.

Alice heard the door open. She did not look around immediately but waited until the doctor said, “Miss Heath?”

Then she put down the magazine carefully and picked up her gloves and turned to him.

He wasn’t frightening, he didn’t even wear a white coat to distinguish him from other young men, to mark him out as a man who dealt with things dark and ugly and never to be talked about. But the uneasiness swept over her again and she made a quick little movement which brought Prince to his feet, alert, ready to leave again, to visit strange places and strange houses, bored and despairing of making sense of any of it.

“I’m Dr. Loring.” He looked at Prince, his eyes uncertain. “Is this your dog?”

She stood mute, shaking her head. She wanted to run out, shouting her explanations over her shoulder as she ran, “You’re too young! I can’t talk to you!”

She didn’t run. She merely put on one glove as a symbol of running.

“It is my sister’s dog,” she said. “My sister Kelsey is blind.”

“Ah,” he said, as if that explained everything. “You’ve come about her, your sister?”

“Yes.”

“All right. Come in here, please.” His voice was professional, matter-of-fact. He stood back from the door and nodded his head slightly. “Do you want to bring the dog in with you?”

“No,” she said quickly. “Oh, no.”

He glanced at her and said, “Ah,” again with the same undertone of smugness, as if his mind were saying, “Aha! All is now clear!”

It irritated her and, to cover up her irritation, she laughed softly, nervously. “He reminds me of a governess I had once. She never missed anything and she never got excited.”

She walked to the door, peeling off her glove again. Her voice had faded into a whisper. Loring closed the door loudly behind them and began to bang things around, a chair for her, his own chair, a lamp that was in his way. When she sat down he continued to make noises; he walked up and down the length of the room; he thrust some papers into the filing cabinet and slammed the door shut again.

She stared at him, her nervousness falling under this barrage of noise and movement. When he saw that she had stopped twisting her gloves he sat down abruptly behind the desk.

She said, “That was very good.”

“What was?” He sounded on guard, suspicious.

“Trying to make me feel at ease. You can’t, of course. Perhaps if you were older...”

“No. You’d have the same difficulty,” he said crisply. “It’s because you’ve come on behalf of someone else. If you yourself were the patient you’d be eager to blurt things out.”

He began to write rapidly on the pad in front of him, hardly bothering to keep his eye on the pen, looking up swiftly at Alice now and then.

“Kelsey. How old?”

“Twenty-six,” Alice said. “Two years younger than I am.”

“Brothers, sisters?”

“One brother, John. He’s thirty.”

“Parents?”

“My mother is dead. She died a year and a half ago of cancer, soon after Kelsey was blinded.”

“Accident?”

“Yes.” She saw his frown of impatience. “Do I tell you about the accident?”

“Is your father living?”

“Yes.”

“All right. The accident.”

“She was driving Johnny’s car that night. They were on their way to a party and...”

“They?”

“Johnny and his girl and Kelsey and Philip James. The girl was killed.”

“Oh.” He looked up, interested. “The girl was killed and your sister blinded. And your sister was driving at the time. The girl was a friend of hers?”

“No. She was with Johnny. She was one of Johnny’s girls. Kelsey had never seen her before.”

“And Mr. James?”

She turned her head and looked out of the window. “Mr. James was — is — engaged to Kelsey.”

Читать дальше

![Маргарет Миллар - Rose's Last Summer [= The Lively Corpse]](/books/384369/margaret-millar-rose-s-last-summer-the-lively-c-thumb.webp)