Маргарет Миллар - The Listening Walls

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Маргарет Миллар - The Listening Walls» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Listening Walls

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- Город:London

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Listening Walls: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Listening Walls»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

When Mrs. Wilma Wyatt crashed to her death from the balcony of her room in a Mexico City hotel, no one knew whether it was an accident, suicide or murder.

And when, shortly after, her friend and travelling companion, Amy Kellogg, disappeared into thin air, the mystery deepened. Did Wilma fall...?

Or was she pushed?

The Listening Walls — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Listening Walls», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Margaret Millar

The Listening Walls

To Vera Cooper, woman of letters

1.

From her resting place in the broom closet Consuela could hear the two American ladies in 404 arguing. The closet was as narrow as the road to heaven and smelled of furniture polish and chlorine, and of Consuela herself. But it was not physical discomfort that disturbed her siesta; it was the strain of trying to understand what the Americans were arguing about. Money? Love? What else was there, Consuela wondered, and wiped the sweat off her forehead and neck with one of the clean towels she was supposed to place in the bathrooms at exactly six o’clock.

It was now seven. She refolded the towel and put it back on the pile. The manager might be a little crazy on the subject of clean towels and exact times, but Consuela was not. A few germs never hurt anybody, especially if no one knew they were there, and what was an hour, one way or the other, in the face of eternity?

Every month the manager, Señor Escamillo, herded the members of the housekeeping staff into one of the banquet rooms, yapping at their heels like a nervous terrier.

“Now hear this. I have had complaints. Yes, complaints. So once again we are here, and once again I say to you the Americans are our most valuable customers. We must keep them so. We must speak always American; we must think American. Now. What do the Americans hate the most passionately? Germs. So we do not give them germs. We give them clean towels. Twice a day, clean towels absolutely without germs. Now, the water. They will ask questions about the water and you will say this water from the tap is the purest water in all of Mexico City. Now. Any questions?”

Consuela had a number of questions, such as why did the manager use bottled water in his office, but self-preservation kept her silent. She needed the job. Her boyfriend had a bent for picking the wrong horses at the Hipódromo, the wrong numbers in the lottery, the wrong jai alai player in the quiniela.

The argument between the two ladies was continuing. Were they arguing about love? Not very likely, Consuela decided. Pedro, the elevator operator and chief spy of the establishment, addressed each of the American ladies as señora, so presumably they had husbands somewhere and were in the city on vacation.

Money? Not likely, either. Both of the ladies looked prosperous. The taller one (Wilma, her friend called her) had a genuine full-length mink coat which she wore constantly, even going down to breakfast; and when she moved along the corridor she clanked like a trolley car she had on so many bracelets. She left nothing behind in her room except a locked suitcase. Consuela had, as a matter of routine, searched through the bureau drawers, and they were all as empty as a sinner’s heart. The locked suitcase and the empty drawers were naturally a great disappointment to Consuela, who had refurbished her wardrobe considerably during the months she’d worked at the hotel. Taking the odd garment here and there was not actually stealing. It was more a matter of common sense, even of justice. If some people were very rich and others very poor, things had to be evened up a bit, and Consuela was doing her part.

“Everything locked,” Consuela muttered among the brooms. “And all those bracelets. Clank, clank, clank.”

She picked four bath towels off the top of the pile, swung them over her left shoulder and stepped out into the hall, a handsome young woman with a haughty tilt to her head. Her confident stride and the casual way she wore the towels made her look like an athlete headed for the showers after a good day on the court or in the field.

Outside 404 she paused a moment to listen, but all anyone could hear, even with ears of a fox, was the roar of traffic from the avenida below. Everyone in the city seemed to be going somewhere, and Consuela had an urge to run down the back stairs and go with them. Her feet, large and flat in their straw espadrilles, ached to be running. But instead they stood quietly outside 404 until the tall one, Wilma, opened the door.

She was dressed to go out to dinner in a red silk suit. Every curl, every ring, every bracelet was in place, but only half her make-up had been applied, so that one eye was dull and pale as a fish’s and the other sparkled with a gold lid and a bright black fringe under a gaily improbable arch. When the paint job was completed she would be, Consuela had to admit, imposing, the kind of woman who would not have to catch the eye of a waiter because his eye would be already on her.

But she is not hembra, Consuela thought. She has no more bosoms than a bull. Let her keep her underwear locked up. It wouldn’t fit me anyway. And Consuela, who was conspicuously hembra, if not downright fat, inflated her chest and rhumbaed her hips through the doorway.

“Oh, it’s you,” Wilma said. “Again.” She turned her back with abrupt annoyance and addressed her companion. “It seems to me every time I take a breath in this place someone’s pussyfooting around turning down beds or changing towels. We get about as much privacy as in a hospital ward.”

Amy Kellogg, standing by the window, made a sound of embarrassed protest, a kind of combination of ssshh and oh dear. The sound was Amy’s own, the resonance of her personality, and an expert could have detected in it the echoes of all the things she hadn’t had the nerve to say in her lifetime, to her parents, her brother Gill, her husband Rupert, her old friend Wilma. She was not, as her brother Gill frequently pointed out, getting any younger. It was time for her to take a firm stand, be decisive and businesslike. Don’t let people walk all over you, he often said, while his own boots went tramp, crunch, grind. Make your own decisions, he said, but every time she did make a decision it was taken away from her and cast aside or improved, as if it were a toy a child had made, crude and grotesque.

Wilma said, giving herself another golden eyelid, “I feel as if someone’s spying on me.”

“They’re only trying to provide good service.”

“The towels she put in this morning stank.”

“I didn’t notice.”

“You smoke. Your sense of smell has deteriorated. Mine hasn’t. They stank.”

“I wish you wouldn’t — do you think you ought to talk like this in front of the girl?”

“She doesn’t understand.”

“But the travel agency said everyone on the hotel staff spoke English.”

“The travel agency is in San Francisco. We’re here.” Wilma made here sound like a synonym for hell. “If she can speak English why doesn’t she say something?”

Wouldn’t you like to know, Consuela thought, swishing cold water nonchalantly around the washbasin. She not speak English, ha! She, who had once lived in Los Angeles, until the immigration authorities had caught up with her father and sent the whole family back with a busload of wetbacks; she, who had a genuine American boyfriend and was the envy of the whole neighborhood because she would one day, with the cooperation of the right horses, numbers and jai alai players, return to Los Angeles and walk among the movie stars. Not speak English! Ho ho to you, Wilma, with no more bosoms than a bull!

“She’s really very pretty,” Amy said. “Don’t you think so?”

“I hadn’t noticed.”

“She is. Terribly pretty,” Amy repeated, watching Consuela’s reflection in the bathroom mirror for some sign that the girl had understood, a blush, a brightening of the eye. But Consuela was an older hand at pretense than Amy was at exposing pretenses. She came out of the bathroom, smiling, bland, and turned down each of the twin beds and plumped up the pillows. For Consuela the pretense was like a game. It could be a dangerous one, if the Americans complained to the manager, who knew she could speak English perfectly. But she couldn’t resist it any more than she could resist pilfering a pretty nylon slip, a gaudy belt, or a pair of lace panties.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

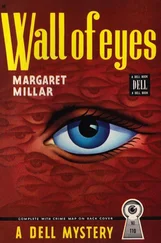

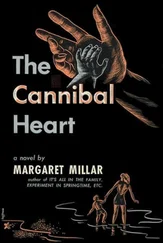

Похожие книги на «The Listening Walls»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Listening Walls» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Listening Walls» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Маргарет Миллар - Rose's Last Summer [= The Lively Corpse]](/books/384369/margaret-millar-rose-s-last-summer-the-lively-c-thumb.webp)

![Маргарет Миллар - The Iron Gates [= Taste of Fears]](/books/433837/margaret-millar-the-iron-gates-taste-of-fears-thumb.webp)