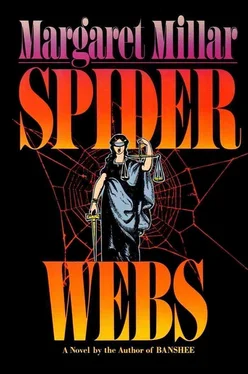

Margaret Millar

Spider Webs

To Sally Ogle Davis and Ivar Davis

Laws are spider webs through which the big flies pass and the little ones get caught.

— Honoré de Balzac

“All rise. Superior Court of the state of California, in and for the county of Santa Felicia, is now in session, Judge George Hazeltine presiding.”

Hazeltine, a tall, spare man in his sixties, moved arthritically toward the bench, trailing his black robe and a strong smell of garlic.

Each morning after breakfast he chewed a clove of garlic, partly for health reasons, partly to help safeguard his privacy. People were not as keen on bothering him with their twaddle if they had to endure a certain amount of nasal discomfort. Attorneys kept their distance, and lesser personnel either spoke from the doorway or didn’t appear at all.

In a rather obvious counterattack his secretary wore a great deal of perfume, most of which, ironically, had been given to her by the judge himself at Christmas, on her birthday and during National Secretaries’ Week. She kept little balls of cotton saturated with perfume tucked into pockets and bras and pinned to the undersides of collars and hems of skirts. Sometimes one of these cotton balls would fall out, and the judge would pick it up and smell it and think: That’s very nice. I have excellent taste in scent.

The judge sat down, cleared his throat and consulted the typewritten page on the lectern in front of him.

“Let the record show that the defendant is present along with his counsel, Mr. Donnelly, and the counsel for the people is present, Mr. Owen, the District Attorney. Let the record also show that the twelve members of the jury are present as well as the six alternates.

“Bailiff, would you kindly pass out the jurors’ badges? These badges will be worn throughout this trial in order to identify the members of the jury and to warn other people to stay away from them and not to converse with them at any time on any topic.”

The badges marked JUROR were handed out by the bailiff and the jurors pinned them to their left shoulders. With the badges in place they looked like oddly assorted delegates to a very solemn convention, environmental activists, perhaps, or anti-abortionists hell-bent on saving the world.

The youngest juror, a carpenter’s apprentice barely twenty-one, brought his motorcycle helmet into court and kept it under his seat. The oldest was a seventy-year-old housewife with a reconstructed face and hair dyed black but turning obstinately orange.

“Ladies and gentlemen, you have heard the clerk read the information, the charges against the defendant, Cully Paul King, being murder and murder for profit to which charges the defendant has pleaded not guilty. It is now time for counsel to make opening statements. I must caution you that anything said in these opening statements is not to be regarded as evidence. Counsel may give you a synopsis of his case and tell you what he expects to prove. Before reaching any conclusions, you must wait until he actually proves it.”

The judge paused. He disapproved of the business of opening statements and the mandatory speech he had to make preceding them. It amounted to telling the jurors they were about to hear a lot of bullshit which they were then obliged to ignore. If the jury was to disregard opening statements as evidence, why bother with them at all?

The system did no credit to the lawyers themselves or to the law, and it was apt to befuddle the jurors and cause them to distrust any statement made by anyone during the course of the trial. It was a poor way to begin a case, forcing the jurors to listen to a whole day or more of oratory which they must then forget they heard.

Utter nonsense. No wonder the judicial system was bogged down.

“The opening statement belongs to the people,” he said. “Are you ready, Mr. Owen?”

“Yes, Your Honor.”

“Proceed.”

The district attorney, Oliver Owen, rose and took his place at the lectern, facing the judge with the jury box on his right. He tested the speaker, which squawked in protest, adjusted it to his height, glanced at his notes and then fixed his eyes on the jury.

He was a good-looking blond man in his forties, and he spoke in a loud, almost belligerent voice as if he were already in the middle of an argument before the case even began.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the court, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I bid you good morning.

“This is a simple case. I’m sure every attempt will be made to give it twists and turns, to confuse the issue by setting up detours. But the fact is, the road ahead is straight and direct, and it leads to one man and one man only, Cully Paul King.

“We, representing the state of California, county of Santa Felicia, intend to prove that Madeline Ruth Pherson, a married woman, met her death at the hands of Cully Paul King.

“Mrs. Pherson, wife of Tyler Pherson, resided in Bakersfield, California. She was forty years of age and in reasonably good health. A recent death in the family left her somewhat depressed, so her husband advised her to spend a week or two on the coast.

“On the morning of May the first she arrived at San Diego’s Playa Airport and took a taxi to Casa Mañana. She was carrying with her two pieces of luggage, consisting of a large suitcase equipped with wheels and a matching one half the size known as a weekender. She also carried a smaller case made of embossed green leather measuring approximately eight by twelve by three inches. She checked into a hotel at Marina del Playa, occupying the suite previously reserved for her by her husband.

“The two larger pieces of luggage were taken up to her suite, but the green leather one was placed in the hotel vault by the assistant manager, Mr. Elfinstone, at Mrs. Pherson’s request. The case had a double lock and weighed about four to five pounds. Because of the double lock and Mrs. Pherson’s request for vault space, Mr. Elfinstone, assistant manager of the hotel, assumed the case contained something of considerable value.

“From her room Mrs. Pherson telephoned her husband to tell him she had arrived safely and was going down to the lobby to people-watch. She seemed in good spirits and said she might even go into the bar and order a drink. The evidence will show that’s exactly what she did.

“It was a fateful decision.

“She was seen at the bar talking to a black man in a navy blue blazer and skipper’s cap; the evidence will show that the man was Cully Paul King, the defendant.

“They talked for some time. Then both parties got up and left the bar, King going into the lobby and Mrs. Pherson to the desk, where she asked for the green case, offering no explanation for her change of mind.

“Carrying the case and a handbag, she went up to her suite and returned shortly afterward to join King in the lobby. Then the two went out together. She was wearing a blue and white striped coat. She did not check out of the hotel, and her clothes were later found carefully hung up in the closet of her suite, her shoes in plastic bags and purses wrapped in tissue paper. She was a meticulous woman. When she put a garment on a hanger, she was careful to button or zip it to keep its shape.

“She was next seen boarding the yacht Bewitched in the company of Mr. King. The crew, Harry Arnold and his teenaged son, Richie, saw her come aboard, carrying the case and wearing the blue and white coat described by Mr. Elfinstone.

“Her gait was unsteady, and Mr. Arnold assumed she’d been drinking. She retired to the captain’s quarters with Mr. King.

“During the day the boat had been cleared by customs and taken on fuel and provisions. It cast off before dawn en route to Santa Felicia. After reaching the open sea, the boat was put on automatic pilot and Harry Arnold went below to sleep. He was scheduled to take the night watch, a necessary precaution in busy shipping lanes where there is often night fog.

Читать дальше

![Маргарет Миллар - Rose's Last Summer [= The Lively Corpse]](/books/384369/margaret-millar-rose-s-last-summer-the-lively-c-thumb.webp)