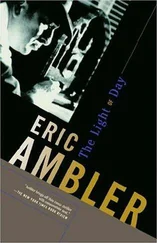

Eric Ambler - Cause for Alarm

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eric Ambler - Cause for Alarm» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cause for Alarm

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cause for Alarm: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cause for Alarm»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cause for Alarm — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cause for Alarm», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“That’s a bit more like it should be. No, don’t dust it any more. Stick it on and give me your own.”

I obeyed him. He surveyed me critically.

“Yes, much better. It’s a good thing you’re dark. That unshaven chin goes swell with the hat.”

I lit a cigarette and yawned. The food had made me sleepy. My eyelids felt very heavy.

“Well,” I said, “I feel like a sleep. What about it? Shall we stay here or try to find somewhere else?”

He did not answer immediately and I looked up from my cigarette. He was looking at me steadily.

“There’ll be no sleep for us to-day,” he said slowly. “We’ve got to get on.”

“But…”

“I didn’t tell you before because I thought I’d let you eat your breakfast in peace, but we’re in a pretty tough spot here.”

My heart sank. “What do you mean?”

“There are patrols out on all the roads.”

“How do you know?”

“I ran slap into one just outside the village. Police and a couple of Blackshirt militiamen. We’re still in the Treviglio area, you see. I had to show my passport and permit, and they were suspicious. I made up a story on the spur of the moment about having started out early from Treviglio to get to a business appointment in Venice and having the car break down. It wasn’t very good, but it was the best thing I could think of to explain what I was doing along this road at this time and in these clothes. They let me by but they took a note of my name and the number of my passport. They also told me where the nearest garage was. I couldn’t very well go back along the road with all those parcels-that would have wanted a bit of explaining-so I had to make a detour through the fields. If they remember me and it occurs to them to check up with the garage man they’ll be beating the bushes before long. And there’s another thing.” He pulled a folded newspaper out of his inside pocket. “Take a look at this. It’s this morning’s.”

I took the paper and scanned the front page. It was an early edition of a Milan sheet. It did not take me long to see what he wanted me to see. There, in the middle of the page were two squared-up half-tones, each about three inches deep. Both were pictures of me.

Above them were the words, “A TTENTI, L. 10,000,” in heavy black capitals. Below, also in bold type, was the message, slightly altered, that had been given over the radio the previous night. I examined the pictures carefully. One had obviously been taken from the prints I had supplied for my permit. It had been a “flat” photograph with hard, sharp lighting. The result was a reproduction that, in spite of the poor paper, was almost as clear as the original. It was easily recognisable as a picture of me. The other was less clear but it interested me very much for it had obviously been made from a photoprint of the photograph on my “lost” passport. I could see faintly where the black impressions of the British Foreign Office stamps had been painted out. I looked up.

“Well,” said Zaleshoff; “now you know why I didn’t want the ticket collector to see your face yesterday. The other papers have got those pictures too.”

“Yes, I see.” I paused. Again I felt fear gripping at my stomach. “What the devil are we to do? If they’re patrolling the roads and everybody’s got these pictures, there’s nothing we can do. You know, I think…”

He interrupted me.

“Sure, I know! You think the best thing you can do is to give yourself up. Don’t, for Heaven’s sake, let’s waste our strength talking all that over again.” He got out the map. “We’re not done yet. All the roads are patrolled but they can’t patrol the fields as well. Now Reminini isn’t marked on this map-it’s too small-but according to my reckoning it’s just about here”-he jabbed the paper with his finger-“and that means that we’re only about thirty kilometres south of the railway line from Bergamo to Brescia. If you’ll look at the map you’ll see that all the major roads run almost due north in this area. In other words, if we go north crosscountry we ought to be able to reach the railway to-day without much risk of running into a patrol.”

“But in daylight…”

“I told you. The only roads we’ll have to worry about are those we cross and they’ll be secondary roads. As for the rest, all we’ve got to do is keep our eyes open.”

I pounced bitterly on the last phrase. “Dammit, Zaleshoff, I can hardly keep my eyes open now. I’m all in. And so are you by the look of it. We shall never do it. It’s no use your sticking your jaw out like that. It just isn’t reasonable to think that we can do it. Anyway, supposing we do get to the railway; what then?”

“We can jump a goods train that’ll take us to Udine.”

“Supposing there isn’t one?”

“There will be. It’s the main goods line from Turin. We may have to hide out until it’s dark, that’s all. And as for feeling tired, you’ll find that if you sprint a bit the tiredness’ll wear off.”

“Sprint!” I could hardly believe my ears.

“Yes, sprint. Come on, change your shoes for the boots and let’s get going. It’s not healthy here.”

I had not the strength to argue any more. I took off my shoes, pulled the coarse woollen socks over my own and then put on the boots. They were very stiff and felt like diving-boots look. My hat and shoes and the bottle and wrappings we buried under the leaves.

We walked through the trees to the fields on the opposite side of the wood to the road: then Zaleshoff produced a small toy compass he had bought in the village. After some trouble with the compass needle which, until we found that the glass was touching it, seemed willing to indicate north in any direction, we marked as our objective a group of trees on the brow of a slope about a kilometre away and set off.

For a minute or two we walked. Then, suddenly, Zaleshoff broke into a sharp trot.

“Race you to the end of the path,” he called back to me.

I detest at the best of times people wanting to race me to the ends of paths. I flung an emphatic negative after him, but he seemed not to hear. Feeling murderous, I picked up my heels and pounded after him. At length we slowed down, panting, to a walk.

“Feeling better?”

I had to admit that I was. The morning breeze had cleared away the remnants of the clouds. There was a suggestion of haze in the middle distance that presaged heat. We could hear a tractor working somewhere nearby, but we saw nothing on legs but cows. For a time we stepped out briskly. Then, as the sun became hotter, I felt my exhaustion returning.

“What about a rest?” I said after a while.

He shook his head. “We’d better keep going. Do you want some cognac?”

“No, thanks.”

We plodded on. It was open farming country with few trees and no shade. Swarms of flies, awakened by the heat, began to worry us. By midday I was feeling horribly thirsty and had a bad headache. For most of the time we seemed to be miles away from any sort of habitation. According to Zaleshoff we should have been near a secondary road running from east to west, but there was no sign of it ahead. The new boots had “drawn” my feet and become intolerably heavy. My legs began to feel shaky. The situation was not improved by our having to waste twenty minutes cowering in a dry ditch out of sight of a labourer who stopped to eat his lunch by the side of a cart track we had to cross. When at last we were able to push on, my feet and ankles had swollen. Our pace became slower. I found myself straggling behind Zaleshoff.

He waited for me to catch up with him.

“If I don’t have a drink of water soon,” I declared, “I shall pass out. As for these damn flies…”

He nodded. “I guess I feel that way too. But we should make the road almost any time now. Can you keep going a bit longer?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cause for Alarm»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cause for Alarm» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cause for Alarm» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.