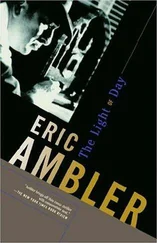

Eric Ambler - Cause for Alarm

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eric Ambler - Cause for Alarm» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cause for Alarm

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cause for Alarm: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cause for Alarm»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cause for Alarm — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cause for Alarm», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There was a pause.

“Well,” I said grimly, “if you really want to know, I think it’s one of the most remarkable pieces of understatement I’ve ever listened to. It sounds like a Sunday-school treat. Auntie Alice will distribute the buns at Udine.”

His brows knitted. He opened his mouth and drew breath to speak.

“But,” I went on firmly, “we’ll leave that side of it out for the moment. What I want to know is why on earth you should choose the Yugo-Slav frontier. What about the French? What about the German?”

He shrugged. “That’s precisely what they’ll say.”

“I see. The French, Swiss and German frontiers are going to be stiff with guards, but the Yugo-Slav frontier’s going to be like the Sahara Desert. Is that right?”

He frowned. “I didn’t say that.”

“No,” I retorted angrily, “but you wish you could. I suppose the fact that we’re going to make for the Yugo-Slav frontier wouldn’t have anything to do with the fact that Vagas is in Belgrade would it? or with the fact that, as I haven’t got a passport, I could not get into Yugo-Slavia from France or Switzerland or Germany without swearing affidavits and heaven knows what else in London first?”

He reddened. “There’s no need to get hot under the collar about it.”

I spluttered furiously. “Hot under the collar! Dammit, Zaleshoff, there are limits…”

He leaned forward eagerly.

“Wait a minute! Don’t forget that you’ve got close on two hundred and fifty dollars to collect from Vagas. It would look perfectly natural for you to make for Belgrade to collect them. For all he knows, you may be flat broke. You will be, anyway, by the time you get to Belgrade. Besides, what difference does it make? If they catch you, you won’t get much change out of them by explaining that you’d decided, after all, not to cause them any more trouble. You started a good job of work. Why not finish it?”

I regarded him sullenly. “I made a fool of myself once. I see no reason why I should do so again.”

He stared at the tablecloth. “You realise, don’t you,” he said slowly, “that without me to help you, you’ll be sunk? You haven’t got enough money. You’ll be caught inside forty-eight hours. You do realise that?”

“I’m not going to wait to be caught.”

He still stared at the tablecloth.

“Nothing will induce you to change your mind?”

“Nothing,” I said decidedly.

But I was wrong.

The proprietor was out of the room, but in the corner of the bar a radio had been quietly churning out an Argentine tango. Suddenly the music stopped. There was a faint hiss from the loudspeaker. Then the announcer started speaking:

“ We interrupt this programme at the request of the Ministry of the Interior to request that all persons keep watch for a foreigner who has escaped from the jurisdiction of the Milan police. He is wanted in connection with grave charges of importance to every loyal Italian. A reward of ten thousand lire, ten thousand lire, will be paid to anyone giving information as to his movements. He is believed to be in the vicinity of Treviglio. He may attempt to pass himself off as an Englishman named Nicholas Marlow. Here is a description of the man…”

Zaleshoff walked over to the instrument and twisted the dial to another station. He returned to the table but did not sit down.

“That’s not a bad price, Marlow, not at all a bad price! They’re doing you proud.”

I did not answer.

He sighed. “Well, I suppose you’ll be wanting the local police post. I wish you joy of it.”

Except for the radio, there was silence in the room. I was conscious that he had walked across the room and was examining the Capri poster.

“If you’re going to telephone your sister before we leave,” I said slowly, “you’d better do it now, hadn’t you?”

I was staring at my empty plate. When I felt his hand on my shoulder, I jumped.

“Nice work, pal!”

I shrugged. “I have no choice.”

“No,” he said softly, “you have no choice.”

14

Zaleshoff was not gone long.

“There’ll be five thousand lire for us at Udine when we get there,” he said when he got back.

“But what about your sister?”

“She’s got some things to clear up, then she’s leaving for Belgrade to keep a line on Vagas. She’ll meet us there.”

“You’ve got everything planned beautifully, haven’t you?” I said, not without bitterness.

“Naturally. It’s better that way.”

He paid the bill and we set out.

For a quarter of a mile or so we retraced our steps; then we struck out in a north-easterly direction.

It was a cold night and cloudy. I was wearing a thin overcoat and I had no scarf; but the pace that Zaleshoff set soon made up for those deficiencies.

To begin with we exchanged a few desultory remarks. Soon we fell silent. Our footsteps grated in unison on the flinty road. My mind seemed with my fingers to have gone numb. I felt emotionally exhausted. All that I was conscious of for a time was a dim, unreasoning resentment of Zaleshoff. He was responsible. But for him, I should be sleeping comfortably in my room at the Parigi. I thought, absurdly, of a favourite shirt I had left among my things there. I should never see that again. I tried to remember where in London I had bought it. Perhaps they wouldn’t have any more shirts like that. Zaleshoff’s fault. Useless to tell myself that Zaleshoff had done no more than make suggestions, that what I was paying for now was the fit of bravado, of temper which had led me that night in Zaleshoff’s office to telephone Vagas. Zaleshoff was the villain of the piece.

Out of the corners of my eyes I glanced at him. I could see him in dim outline, his hands in his pockets, his shoulders hunched, plodding along beside me. I wondered if he was conscious of my dislike, of my mistrust of him. He probably was. He did not miss very much.

And then I had a sudden revulsion of feeling. It was not true to say that I disliked him; you could not dislike him. I felt suddenly that I wanted to put out my hand and touch his arm and shake it to show that I bore him no ill-will. I wondered idly, unemotionally, if, had Vagas already received my second report, or had Zaleshoff been able to transmit it to him in any other way but through me, I should have been helped in this way. Probably not. I should have been left negligently to my fate. Zaleshoff was a Soviet agent-I had come without effort to take that fact for granted-and he had his work to do, he had the business of his extraordinary government to attend to. I supposed that, strictly speaking, I, too, was a servant of that government. Oddly enough, I found that idea no worse than curious. Vagas’ suggestion that I was a servant of his government I had found highly-distasteful. Perhaps that was because I liked Zaleshoff and disliked Vagas, or because one had paid me and the other had merely offered to do so. Still, it was odd. After all, I had no particular feelings about either of their countries. I knew neither of them. When I thought of Germany I thought of parades, of swastika banners flapping from tall poles, of loudspeakers, of stout field marshals and goose-stepping men with steel helmets, of concentration camps. When I thought of Russia I thought of dark, stupid Romanoffs, of the Winter Palace, of Cossacks, of crowds streaming in terror, of canopied priests swinging censers, of Lenin and Stalin, of grain rippling in the breeze, of the Lubianka prison. Yes, it was odd. I found suddenly that we were slowing down. Then Zaleshoff cleared his throat and muttered that we turned right. We passed the fork in the road and increased our speed again. The moon shone for a moment through a thin patch in the drifting clouds, then disappeared again. In the darkness the silence walked with us like a ghost.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cause for Alarm»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cause for Alarm» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cause for Alarm» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.