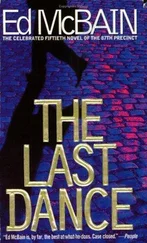

Ed McBain - The Last Brief

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ed McBain - The Last Brief» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1982, ISBN: 1982, Издательство: Arbor House, Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Brief

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arbor House

- Жанр:

- Год:1982

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0877955306

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Brief: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Brief»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Brief — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Brief», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Ah, what the hell.

That’s show biz.

The Prisoner

They were telling the same tired jokes in the squadroom when Randolph came in with his prisoner.

Outside the grilled windows, October lay like a copper coin, and the sun struck only glancing blows at the pavement. The season had changed, but the jokes had not, and the climate inside the squadroom was one of stale cigarette smoke and male perspiration. For a tired moment, Randolph had the feeling that the room was suspended in time, unchanging, unmoving and that he would see the same faces and hear the same jokes until he was an old, old man.

He had led the girl up the precinct steps, past the hanging green globes, past the desk in the entrance corridor, nodding perfunctorily at the desk sergeant. He had walked beneath the white sign with its black-lettered DETECTIVE DIVISION and its pointing hand, and then had climbed the steps to the second floor of the building, never once looking back at the girl, knowing that in her terror and uncertainty she was following him. When he reached the slatted rail divider, which separated the corridor from the detective squadroom, he heard Burroughs telling his old joke, and perhaps it was the joke which caused him to turn harshly to the girl.

‘Sit down,’ he said. ‘On that bench!’

The girl winced at the sound of his voice. She was a thin girl wearing a straight skirt and a faded green cardigan. Her hair was a bleached blonde, the roots growing in brown. She had wide blue eyes, and they served as the focal point of an otherwise uninteresting face. She had slashed lipstick across her mouth in a wide, garish red smear. She flinched when Randolph spoke, and then she backed away from him and went to sit on the wooden bench in the corridor, opposite the men’s room.

Randolph glanced at her briefly, the way he would look at a bulletin board notice about the Policeman’s Ball. Then he pushed through the rail divider and walked directly to Burroughs’ desk.

‘Any calls?’ he asked.

‘Oh, hi, Frank,’ Burroughs said. ‘No calls. You’re interrupting a joke.’

‘I’m sure it’s hilarious.’

‘Well, I think it’s pretty funny,’ Burroughs said defensively.

‘I thought it was pretty funny, too,’ Randolph said, ‘For the first hundred times.’

He stood over Burroughs’ desk, a tall man with close-cropped brown hair and lustreless brown eyes. His nose had been broken once in a street fight, and together with the hard, unyielding line of his mouth, it gave his face an over-all look of meanness. He knew he was intimidating Burroughs, but he didn’t much give a damn. He almost wished that Burroughs would really take offence and come out of the chair fighting. There was nothing he’d have liked better than to knock Burroughs on his ass.

‘You don’t like the jokes, you don’t have to listen,’ Burroughs said, but his voice lacked conviction.

‘Thank you. I won’t.’

From a typewriter at the next desk Dave Fields looked up. Fields was a big cop with shrewd blue eyes and a friendly smile. The smile belied the fact that he could be the toughest cop in the precinct when he wanted to.

‘What’s eating you, Frank?’ he asked, smiling.

‘Nothing. What’s eating you?’

Fields continued smiling. ‘You looking for a fight?’ he asked.

Randolph studied him. He had seen Fields in action, and he was not particularly anxious to provoke him. He wanted to smile back and say something like, ‘Ah, the hell with it. I’m just down in the dumps’—anything to let Fields know he had no real quarrel with him. But something else inside him took over, something that had not been a part of him long ago.

He held Fields’ eyes with his own. ‘Any time you’re ready for one,’ he said, and there was no smile on his mouth.

‘He’s got the crud,’ Fields said. ‘Every month or so, the bulls in this precinct get the crud. It’s from dealing with criminal types.’

He recognized Fields’ manoeuvre and was grateful for it. Fields was smoothing it over. Fields didn’t want trouble, and so he was joking his way out of it now, handling it as it should have been handled. But whereas he realized Fields was being the bigger of the two men, he was still immensely satisfied that he had not backed down. Yet his satisfaction rankled.

‘I’ll give you some advice,’ Fields said. ‘You want some advice, Frank? Free?’

‘Go ahead,’ Randolph said.

‘Don’t let it get you. The trouble with being a cop in a precinct like this one is that you begin to imagine everybody in the world is crooked. That just ain’t so.’

‘No, huh?’

‘Believe me, Frank, it ain’t.’

‘Thanks,’ Randolph said. ‘I’ve been a cop in this precinct for eight years now. I don’t need advice on how to be a cop in this precinct.’

‘I’m not giving you that kind of advice. I’m telling you how to be a man when you leave this precinct.’

For a moment, Randolph was silent. Then he said, ‘I haven’t had any complaints.’

‘Frank,’ Fields said softly, ‘your best friends won’t tell you.’

‘Then they’re not my best...’

‘All right, get in there!’ a voice in the corridor shouted.

Randolph turned. He saw Boglio first, and then he saw the man with Boglio. The man was small and thin with a narrow moustache. He had brown eyes and lank brown hair, and he wet his moustache nervously with his tongue.

‘Over there!’ Boglio shouted. ‘Against the wall!’

‘What’ve you got, Rudy?’ Randolph asked.

‘I got a punk,’ Boglio said. He turned to the man and bellowed, ‘You hear me? Get the hell over against that wall!’

‘What’d he do?’ Fields asked.

Boglio didn’t answer. He shoved out at the man, slamming him against the wall alongside the filing cabinets. ‘What’s your name?’ he shouted.

‘Arthur,’ the man said.

‘Arthur what?

‘Arthur Semmers.’

‘You drunk, Semmers?’

‘No.’

‘Are you high?’

‘What?’

‘Are you on junk?’

‘What’s — I don’t understand what you mean.’

‘Narcotics. Answer me, Semmers’.

‘Narcotics? Me? No, I ain’t never touched it, I swear.’

‘I’m gonna ask you some questions, Semmers,’ Boglio said. ‘You want to get this, Frank?’

‘I’ve got a prisoner outside,’ Randolph said.

‘The little girl on the bench?’ Boglio asked. His eyes locked with Randolph’s for a moment. ‘That can wait. This is business.’

‘Okay,’ Randolph said. He took a pad from his back pocket and sat in a straight-backed chair near where Semmers stood crouched against the wall.

‘Name’s Arthur Semmers,’ Boglio said. ‘You got that, Frank?’

‘Spell it,’ Randolph said.

‘S-E-M-M-E-R-S,’ Semmers said.

‘How old are you, Semmers?’ Boglio asked.

‘Thirty-one.’

‘Born in this country?’

‘Sure. Hey, what do you take me for, a greenhorn? Sure, I was born right here.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘Eighteen-twelve South Fourth.’

‘You getting this, Frank?’

‘I’m getting it,’ Randolph said.

‘All right, Semmers, tell me about it.’

‘What do you want to know?’

‘I want to know why you cut up that kid.’

‘I didn’t cut up nobody.’

‘Semmers, let’s get something straight. You’re in a squadroom now, you dig me? You ain’t out in the street where we play the game by your rules. This is my ball park, Semmers. You don’t play the game my way, and you’re gonna wind up with the bat rammed down your throat.’

‘I still didn’t cut up nobody.’

‘Okay, Semmers,’ Boglio said. ‘Let’s start it this way. Were you on Ashley Avenue, or weren’t you?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Brief»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Brief» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Brief» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.