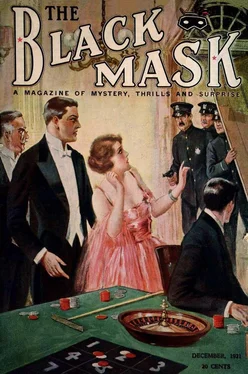

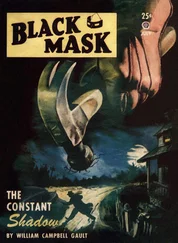

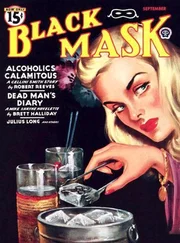

Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1921, Издательство: Pro-distributors Publishing Company, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pro-distributors Publishing Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1921

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

III

Late afternoon had set in; and the dusk revealed nothing but a long row of square glass cases standing upon a trestle and emanating a sickly greenish light in the afterglow which slanted down through the skylight.

Slade switched on some incandescents.

Details leaped out at Arbuthnot. He noted that some of the glass tanks contained a fluid, while others were dry. Electric wires were connected with each, and thermometers indicated their interior heat. Faint stirrings — a little scraping on the sand of one of the dry containers — indicated some sort of life within. Slade touched his sleeve and directed him to the end of the row.

Peering within, the alienist made out some creature which he could not identify, nor even classify as plant or animal. It swayed gently in the water, its eight or nine inches erect, with a bulbous head and a suggestion of human features; but its limbs were like some unwholesome plant, with twigs for hands and feet. It seemed rooted in a yellowish-gray clay at the bottom of the tank. Little bubbles rose continuously from its mouth.

“Part man — part seaweed,” observed Slade. “What do you think of it?”

Arbuthnot bent closely over the stagnant water. A feeling of horror crept through his veins like iced water. The homunculus turned its head — if it was a head — upward, and its eyes, whitish and without expression, seemed to look through the viscous fluid into his own. A rudimentary nose — a wide mouth — sessile ears — these he made out before the thing seemed to take fright and slithered down to burrow into the clay in which its lower limbs were rooted.

Without a comment Arbuthnot permitted himself to be led to the next tank.

Here was, unquestionably, a miniature woman. Beautiful and shapely as a fairy, with perfect breasts and an exquisite little head swaying upon a slender neck, her skin shimmered silvery-green in the water. Arbuthnot turned deathly sick as he saw that below the waist she — it — was seemingly a slimy eel!

Concerning the occupants of the other glass boxes he retained only a jangled sense of hideous and unclassifiable monstrosities. There were serpents that were part vegetable; plants that mocked humanity. There were other things that fascinated by a sort of loathsome beauty. Sickened to the soul, he was dragged back to a consciousness of the present by the low-pitched voice of John Slade, whose presence he had forgotten.

“I don’t suppose that I can possibly explain my feelings toward these little creatures. We have no adjectives, no similes for it — because it isn’t a human emotion. I am the first man ever to know it. There is nothing of sex in it, you see; nothing comparable to love of wife, or parents, or offspring. It is the yearning of the creator over the people he has created. God feels it, I suppose, for us; but in depicting God’s love we grope for words and say that he cares for us as a father for his son.”

He moved from the blue-green tanks with their faint stirrings of a nameless life shadowing the translucent glass. At the end of the screen he turned to look squarely back at Arbuthnot.

“Although a narrow and unimaginative man, you are an honest one,” he said. “You will know what to do. I am going back to nothingness!”

The physician heard him cross the room, caught the soft click of the lever as he threw open the great steel door. He leaped forward, overturning the screen, and beheld Slade with a quick motion cast aside his single garment and shuffle off his sandals. His naked body stood out for a second against the dark interior of the metal closet; and then the door closed noiselessly behind him.

Arbuthnot’s impulse to rush forward and open the door was arrested by a deep, musical tone which came from the closet. Slowly, and by infinitesimal tonal shadings, it rose through the scale, culminating at length in an incredibly thin and high note, like the keenest harmonic of a violin. It died away into silence; but he had a feeling that the sound was still mounting up and up, though now far beyond the range of his ear. Then he turned, steadily enough, and switched on the current in the electric incinerator.

The half-hour that followed was never anything save a horrible nightmare. The details were not clear, and he made no effort to recall them. On many a sleepless night he prayed to be able to forget them all.

When the furnace was white hot he began dropping into it, one by one, the living organisms from their glass tanks. As he moved back and forth, there were times when he felt that he was a malignant deity destroying a world. A sense of megalomania, like that induced by certain drugs, obsessed him. The poor creatures didn’t want to die; that was plain enough. They clung to their bleak, arid lives, and they feared and hated him. When Slade had approached their tanks they had evinced a feeble pleasure or, at least, a sluggish indifference. But from Arbuthnot they shrank, seeking to hide away among the pebbles and sand and fragments of coral. And into his mind came the words of Scripture, how on the Last Day the human mites shall call upon the mountains to cover them!

The little tree-man fought with a futile rage, seeking to bite his fingers, and making no more impression upon the skin than if it had been buffalo hide. Its tiny twig-like fingers struggled ceaselessly; and it seemed to feel acute pain as he uprooted it from its bed of clay. But the eel-woman offered no resistance; and her tragic despair was the harder to bear. She covered her wee breasts with her hands, and tears unbelievably minute rolled down her face.

Down Arbuthnot’s streams of perspiration poured, as one by one he dropped Slade’s creations hissing into the white-hot incinerator. When at length he had done, ending by burning the great book filled with the formulae which might conceivably enable another to recreate a forbidden microcosm, his limbs were trembling and his pulse racing.

Ordinarily, he would have dreaded to open the steel door which Slade had closed behind him; but after what he had done, anything else seemed commonplace. His nerves refused to react further. Listlessly, and almost incuriously, he crossed the room, turned the lever and pulled open the door.

A wave of heated air swept out, stirring the damp hair upon his forehead. But there was no one inside.

The steel closet was shining and empty.

Fit for a King

by Walter Deffenbaugh

I

Men who read books, with whom I have talked more than a little in my spare time, are fond of quoting Shakespeare. Perhaps they quote others, but mine is a mind like President Wilson’s — one poetic train is enough on my single-track — and so I can’t remember the rest. One quotation sticks particularly in my memory.

It is something about “There is a tide in human affairs which, taken at its flood, leads on to victory.” Perhaps that isn’t quite right. It has been a long time since I have read it, because working up and down the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the beaches of the North Pacific, one can’t carry much of a library.

But what made it stick with me was that thing in it about the tide. You know the tide and the waves are like a woman; they can’t keep anything secret for very long. Just give them time and they will tell all about it. A woman can’t keep a secret — neither can the sea.

That fellow knew what he was talking about when he wrote that, but he did not know it half so well as we did, because he did not know how much we depend on the tide and the surf for our tips on what the smugglers and other criminals are doing along our uninhabited coasts. If it were not for the help of the sea we would surely be lost.

It was a wave — a big one, unwelcome at the time, unasked and rough, as waves usually are — that solved for me one of the greatest mysteries our service was ever called upon to run down, and one which had baffled our best men for more than a year.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.