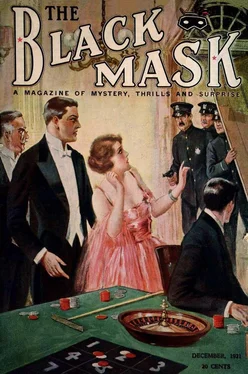

Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1921, Издательство: Pro-distributors Publishing Company, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pro-distributors Publishing Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1921

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“My father,” he said, “I have paid your debt to the white barbarian and also I have collected that which Li Sing owed you.”

The old man nodded his head gently.

“You have done well, my son. Tell me now the details.”

Chu Kwong cleared his throat.

“I found the white barbarian sick, O my father. And I removed from his person that which was gnawing at his heart. I permitted Li Sing to be my servant in the matter and for his services absolved him from his debt.”

He drew forth a clipping from a London newspaper, and translating slowly, read it to his father:

All London was shocked by the brutal murder of Lady Miriam Westlake. The horrible event took place last night as the deceased was leaving the Haymarket Theatre in the company of her husband. According to witnesses, a short, stout man sprang from the crowd and silently plunged a long knife into her back. In the ensuing excitement the assailant escaped and there was no one who saw his face clearly enough to identify him. Charles Hornby, baker, of Reading, swears that the man was a Chinaman, but Inspector Grant, who is investigating the case, believes this to be highly improbable.

Chu Kwong folded the clipping and returned it to his pocket. Then he looked gravely at his father.

The old man removed the stem of his pipe from between his lips and spat contemplatively.

“I do not quite follow all the details of this matter, my son,” he said. “But undoubtedly you have done well.”

Chu Kwong half turned away.

“And if in paying your debt, O my father, I have paid it partly with my heart’s blood, have I acquired virtue?”

The old man nodded.

“You have acquired great virtue, my son.”

Chu Kwong bowed his head.

“Perhaps that is so,” he said softly.

The Man Who Knew Too Much

by John D. Swain

I

“The trouble with me,” said the last patient of the day, “is that I know too much.”

The statement did not surprise Arbuthnot, the consulting alienist. The patient who had just left his office had assured him that he was perfectly all right save for a glass heart, which he lived in constant terror of cracking by colliding with somebody, or by slipping on a wet pavement.

Before him, there had been a pretty girl bubbling with enthusiasm over a scheme for curing stammerers by intra-venal injections of parrot’s blood. And so it went, every afternoon from two until four. Arbuthnot elevated his brows politely, and gazed upon the pale, emaciated man of sixty-odd who faced him across the wide table.

“You know too much — about what?”

“Everything! Big things, and trifles. All my senses are abnormally keen. Without in the least wishing to do so, I overheard all your conversation with the patients who preceded me, through your soundproof door. Coming downtown, I passed seven hundred and thirteen pedestrians; and I could describe each one so minutely that any reasonably intelligent police officer could identify him at sight. On the street cars, I can hear the ticking of every watch, and distinguish the minute differences in beat and pitch. Yesterday I rode for two miles along the principal business street of a Jersey city. I can write out for you every sign, every scrap of lettering on the shop fronts of the side I was facing, along the entire route. When I smell a perfume, I at once identify each of the dozen or more coal-tar derivatives from which it has been built up.”

Dr. Arbuthnot nodded.

“I have treated cases not unlike yours,” he said. “There is no cause for alarm. You are probably overworking. Drop everything and play for a while. Golf. Or long tramps in the country.”

“No use. I should count the apples on the trees, and if I laid down to rest I should hear the grass grow and the earthworms burrowing far beneath. I can stand it daytimes, but of late my mind retains its activity until I sink into a sort of stupor toward dawn. I am sixty-three, and I’ve never used drugs of any sort. Now I want something to make me sleep, at least every other night.”

The alienist made the customary examination, with stethoscope and opthalmoscope; tested his reflexes, and questioned him upon his family history.

John Slade’s father had been of a type not uncommon in rural New England, although dying out. Self-taught, save for what the village academy could impart, he knew a little about many things. He was a naturalist, of sorts. Was always pointing out glacial scratches on the rocks in the neighborhood, and finding Indian arrowheads. Had a fine collection of butterflies, and knew them all by their Latin names. Botanized a great deal by day, and read the stars by night through a rusty old telescope. Understood the ways of

fishes and wood creatures. Could enjoy his New Testament in both Greek and Latin. With his hands he was able to repair sewing machines, pumps, typewriters, or clocks, and could design and build a modest house unaided. Knew surveying, and served as the local undertaker. With two or three simple tools he could do things that would have baffled a master mechanic, — yet could not have passed an examination as plumber’s assistant. A gentle, visionary man, the only resident of his county to whom Spinoza and Descartes and Einstein meant anything at all, he lived and died as poor as a church mouse.

Slade’s mother was a French-Canadian, unable to read or write. She had the illiterate peasant’s extraordinary powers of minute observation, was a neat housewife, a mixture of cunning and credulity, and a devout Christian.

John Slade himself cared nothing for money. When he needed any, he invented something. His education, begun by tramping the countrywide with his father and absorbing all sorts of ill-assorted facts, had been pursued in many lands. At one time he buried himself in Johns Hopkins, engrossed in biology and embryology. Next he was heard of at Oxford, steeped in mediævalism. Physics at Leipsic and Prague. Chemistry at Bonn. Back again to the States, he flitted from Massachusetts ’Tech to the Edison laboratories. Always learning. Never producing — save when lack of funds drove him to some hack work: a course of lectures before the Lowell Institute, the invention of a crankless ice-cream freezer, an article for some technical publication.

“I know too much,” he repeated after answering all of Arbuthnot’s questions. “That is the trouble. And now I cannot sleep!”

The physician gave him some advice as to exercise and diet, to which he listened abstractedly. Then he handed him a little vial of the lethal tablets which would, for a time at least, permit his distracted brain to forget.

Usually he was able to dismiss his patients from his mind after he had done what he could for them, and filed their cards away. He did not find it so easy to forget Slade.

For one thing, he came upon articles written by him from time to time, in the journals to which he subscribed. His fellow practitioners mentioned him occasionally. Slade was a sort of mystery, and it was admitted that he knew more about embryology and chemistry than they did themselves. Nobody could tell just how much the fellow did know! Whatever he said or wrote was uttered with authority and was hard to refute. He had a laboratory which none of them had ever seen, and where it was rumored that he carried on extraordinary experiments, the nature of which was unknown.

Nevertheless, Arbuthnot had very nearly forgotten him when, six months after his call, he received a brief note requesting the alienist to visit him the following afternoon, upon a matter of life and death.

II

Promptly upon the departure of his last patient at a little after four next day, Arbuthnot stepped into the taxicab he had already summoned, and fifteen minutes later was admitted by John Slade himself to his quarters on the top floor of a wholesale storage house well downtown. There was nobody about except the janitor, who took him up in a rickety freight elevator and indicated the door bearing Slade’s card.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.