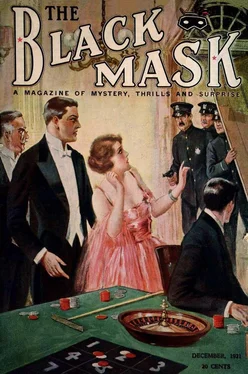

Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Meredith Beyers - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1921, Издательство: Pro-distributors Publishing Company, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pro-distributors Publishing Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1921

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Stored up in Westlake’s heart was all the love and affection accumulated by a man who has lived a lonely life in strange lands. All of it he lavished on his wife. He gave her himself wholly and for eternity. And the greater tragedy was not that she refused his gift, but that she seemed unaware that it had been offered. A week after they were married she went her usual way — a ceaseless round of receptions, dinners, dances — and her husband had become simply another of those possessions one has but doesn’t think about.

It was shortly after her return from the Glencairn shooting that she met an undersecretary at the Chinese Embassy, a certain Chu Kwong, who was greatly the rage because he could sing exotic love-songs to strange Chinese music.

“Oh, do bring the dear child over and present him,” she said to her host at the Spanish Ambassador’s reception.

Don Ruy Diaz laughed and sent one of his aides to fetch the good-looking young Chinaman.

When Chu Kwong heard Lady Miriam’s name he smiled pleasantly into her eyes.

“Your father — perhaps he is Mr. Gregory Westlake?” he asked in his so-ft, almost feminine, voice.

“That is my husband’s name,” Lady Miriam replied.

Chu Kwong clasped his hands together and bowed very low.

“Then we should be friends, madam, since already I am your husband’s friend.”

“You know my husband?”

“Alas, no, madam,” Chu Kwong answered. “Nevertheless I am his friend.”

And bowing again, he moved slowly away.

Intrigued by his perfect self-possession, his quaint manner, Lady Miriam determined to add Chu Kwong to the host of her admirers.

It was not a difficult task. Chu Kwong was at the age of idealism when any pretty woman who will listen to a young man’s hopes and aspirations is an angel in disguise. And Lady Miriam had the knack of listening.

She let him come to tea and over the cups draw her a picture of a new China with himself in the foreground holding a very important position indeed. She let him bring her little presents — queer fans of sandalwood and ornaments of apple-green jade. It was her whim to captivate him and she gratified it.

Chu Kwong’s attitude toward Westlake was odd. Gifted with the Oriental’s ability to penetrate to another’s moods, he saw clearly beneath Westlake’s mask of nonchalance. He saw that the man was unhappy — unspeakably so. And not knowing that the cause was Lady Miriam’s indifference and neglect, he was possessed with a measure of contempt for his father’s friend.

To a Chinaman, possession of a desirable woman is more than nine points of the law. It is the law complete. How, then, could a man married to Lady Miriam, living in the same house with her, privileged to enjoy the thousand and one intimacies of such living, dare to be anything but overwhelmingly joyous? Did it not augur a lack of taste and appreciation for so enviable a being to be unhappy?

Nevertheless Chu Kwong, bound by filial devotion, never lost sight of the fact that it was to this Englishman that his father owed his life. And always his eyes were open, seeking here, seeking the opportunity to pay his father’s debt.

And it came about that one afternoon he called at the Westlake house to escort Lady Miriam to a sale at Christies. The servant put him in the little drawing-room behind which was Westlake’s library.

For a little Chu Kwong sat beside the window looking out into the quiet street. Then growing restless, he rose and began pacing up and down the length of the room. As he neared the folding door leading to the library he heard voices.

Matters of morals and good taste vary greatly. A Chinaman can listen behind a closed door without forfeiting his self-respect. So Chu Kwong stood very still and listened.

A man’s voice that Chu Kwong had never heard before was speaking.

“... and from there we’ll take native boats to the river’s source. The shooting is bound to be good. Will you come, Gregory?”

And Westlake replied:

“Sorry, old chap. Like to and all that. But I–I can’t.”

There was silence for a minute. Then the strange voice broke out, its tones impatient:

“I know what it is. I think that you are hugging your misery to your heart. Forgive me for speaking like this, Gregory, but — well, damn it all, I hate to see a good chap come a cropper because a petticoat can’t see he’s the finest man on two continents.”

There was the sound of a chair being pushed back, followed by an exclamation from Westlake:

“Gad, man, it isn’t pretty, is it — to see your pal making all kinds of an ass of himself!”

He laughed. Then his voice became serious.

“But truly you don’t understand. No man could who hadn’t been in the same boat. Miriam is in my blood — like that damnable African fever. And you can’t get rid of it and you can’t forget it — ever. I know I’m not wanted here: wouldn’t even be missed if I trekked anywhere, but — well, I can’t go.”

“See here,” he went on after a short pause, “to no other man on earth would I tell these things. Do you know that sometimes I am almost ready to pray for Miriam’s death, so that once irrevocably separated from her I can pull myself together and be my own man again.”

Then someone entered the library and the conversation ceased.

That evening Chu Kwong sat long and motionless, absorbed in his thoughts. Knowledge, ideas, suggestions that had come to him from hearing Westlake talking to his friend crowded his brain and bewildered him. One by one he sorted them and weighed them and placed them in their proper relationship. And it seemed to him when he was done that his duty was clear.

Then in his whole being there raged a battle between duty and desire. It lasted until the dawn had lighted up the chimney-pots and paled the stars. It left Chu Kwong exhausted, but around his lips there were lines of purpose and determination.

The next morning he visited Li Sing, importer of teas and spices and perhaps a little of the juice of the yellow poppy.

After he and his host had accomplished the necessary ceremonies of greeting, he came to the purpose of his call.

“Li Sing,” he said, “there is a debt of money that you owe my father.”

The other Chinaman moved his huge bulk uneasily. He coughed behind his hand, shaking his head sadly.

“That is true, O elder brother.”

“And you can pay?”

Li Sing grew still more embarrassed.

“My business is poor, son of an illustrious father, and I have no money.”

Chu Kwong’s eyes narrowed.

“Debts may be paid in other ways than with money,” he suggested.

Li Sing’s face brightened.

“What is it that you wish me to do?”

Chu Kwong leaned over him and whispered a sentence or two into his ear.

The other man sprang to his feet.

“No! No!” he cried. “That is impossible.”

“Why?”

Li Sing stretched forth his hands appealingly.

“But can you not see? There is the danger to my life.”

Chu Kwong, sitting as immovable as an idol, looked at him coldly.

“But there is the danger to your honor if you do not do as I have asked,” he said brutally. “Shall your ancestors lose face because you are a cheat and a coward?”

Then Li Sing fell upon his knees and pleaded. But to all his offers and protestations Chu Kwong turned a deaf ear. His eyes were veiled with the mist of incomprehension, as though he could not understand the other’s words.

At last Li Sing rose. He made a little gesture of defeat.

“I will do as you have ordered,” he said quietly.

“That is well,” Chu Kwong replied.

Then he, too, rose and departed.

III

Chu Kwong again stood humbly before his father.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 4, No. 3 — December 1921)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.