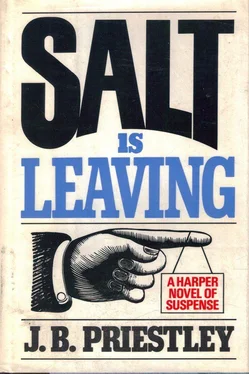

J.B. Priestley

Salt is Leaving

SALT IS LEAVING

by

J. B. PRIESTLEY

Salt is Leaving by J. B. Priestley

First published as a paperback original by Pan Books in 1966

Copyright © 1966 by J. B. Priestley, renewed 1994

CHAPTER ONE

A Father is Missing

1

A few years ago, W. H. Smith had no branch in the High Street, Hemton. ( County town of Hemtonshire; population 13,600; early closing Thursday; Market Day Friday; see medieval Guild Hall and almshouses, University of Hemtonshire – 2 miles N.E. on Hemton-Birkden rd .) Where Smiths are so bright and imposing now, then there was a smaller and far less imposing shop: E. Culworth , Bookseller and Stationer . And it was at the back of this shop, towards closing time on a Monday in early October, that Maggie, only daughter of E. Culworth, might be said to have first set foot in the maze that finally turned into a high road.

She had spent all the afternoon doing accounts in the little office at the back. Now she came out to ask her father to sign some cheques. In the near room, with children's books on one side and paperbacks on the other, Sheila Holt was pulling her mouth down to give it more lipstick.

"Where's Mr Culworth?" Maggie asked her.

Sheila stopped lipsticking. "I don't know, I'm sure." This was not surprising. At work she wasn't sure of anything except that she didn't know.

Maggie looked through the archway into the larger room, which led to the street door. Mrs Chapman was attending to a customer, the only one in sight, at the stationery, fountain pens and gifts counter. The old reliable gave Maggie one of her slow fat smiles. Not seeing either her father or the boy, Reg Morgan, Maggie thought they might be rearranging some of the secondhand books down in the basement. The lights were on down there. Beginning to feel impatient, Maggie rushed below, risking a fall at the turn of the stairs.

"Don't overdo it, Reg." Still holding a duster in one hand, he was deep in a book. He was smallish even for sixteen and had a curiously wizened face, so that at times he looked like a professor on the edge of retirement. He wasn't stupid like Sheila, who, Maggie guessed, never really thought about anything except young men, making love, bedroom suites and where she would spend her honeymoon. Reg, poor lad, failed all examinations and yet carried about with him a kind of bookworm atmosphere; her father believed he might be turned into a first-rate assistant. But where was her father?

"I don't know, Miss Culworth. He told me this morning to come down here and tidy up and make more room in the top shelves. Sounded as if he might be going off to some auction sale – y"know, to buy some more secondhands."

"Yes, I suppose that's it, Reg. But he almost always tells me. Well, you can pack up now. And don't forget to turn the lights off." She hurried upstairs.

Mrs Chapman's customer had gone, and she was clearing away, ready to close the shop. Once a teacher, married and then widowed in her forties, now well into her fifties, fat and comfortable but very conscientious, Bertha Chapman had been her father's chief assistant for years when Maggie came back from London and agreed to work in the shop, taking charge of accounts and correspondence.

"What's the matter, Maggie?"

"It's my father, Bertha. Where is he? There are cheques and things for him to sign."

"He's not been in all afternoon. Didn't he tell you at lunch-time where he was going?"

"I don't go home for lunch on Mondays, Bertha. Mother gets up early on Mondays and does some washing, then she meets her friend Mrs Holroyd somewhere for coffee and cakes, and then they go out to the Cottage Hospital and spend the rest of the day there, doing mysterious good works. So at half past twelve I nip round to the Primrose for some coffee and two poached eggs or one of their rather revolting little messes-"

"And your father goes to the Red Lion for a glass of bitter and a couple of sandwiches," said Mrs Chapman, smiling. "Usually about one o"clock. Well, I can tell you this, Maggie. He went earlier today – about quarter to one. He took a telephone call in the office, and then went straight off, without a word. And he looked worried – really worried. He often looks anxious – he's an anxious kind of man, your father is, Maggie, as you must know as well as I do. But this time he looked so worried and in such a hurry to get away, I didn't like to stop him and ask him where he was going." She was serious now.

Maggie knew that Bertha Chapman was no fusspot. She felt disturbed, but pretended not to be. "Probably somebody rang him up to remind him about some sale he's forgotten, so he rushed off to it." She looked hopefully at Bertha, who was now crumpling a paper on which somebody had been trying a fountain pen. "Don't you think so, Bertha?"

After disposing of the crumpled paper, Bertha gave her a long, hard look. "I'm afraid I don"t, Maggie. Your father isn't going to try rare books again, and he doesn't want to carry much more secondhand stock. But that's not it. I know his anxious business face – I ought to after all this time – but the way he looked when he went out today was quite different. He wasn't thinking about this shop. He was worried about something else. But that doesn't mean you have to worry about it, Maggie. Better not, I say."

"And you"re sure you don't know what it might be?" It was Maggie's turn now to stare hard.

"I couldn't even start guessing, Maggie. We'd better close up, hadn't we?"

Maggie liked to walk briskly, and as a rule she was home in ten minutes. But this time it took her nearly quarter of an hour. Not being afraid of taking an interior look at herself, she realized as she approached the house that she had been deliberately loitering a little in the hope she would find her father already there. He might have decided, she told herself, that it was not worth while to return to the shop at closing time. He might. It was just possible. But she was not surprised when she had to unlock the front door. Her mother would still be at the Cottage Hospital; her brother Alan at the University, where he lectured on physics; and wherever her father was, he certainly wasn't back home.

It was a tallish but narrow house, one of a row of twelve built about 1900. Everything except the stairs was to the right of something that began as a hall and ended as a passage to the kitchen. In front was the sitting room and behind it was the dining room, close to the kitchen. Her parents had the large front bedroom and she had the back bedroom, too poky even after the bed-sitter she had had in London. Alan claimed both attic rooms, sleeping in one and filling the other with books, his moths and other nonsense. Maggie had often complained that the house was now too small for them – she couldn't begin to turn her miserable room into a bed-sitter – and that anyhow it had far too many useless things in it. But this evening, for once, it seemed quite large – and disturbingly empty. Halting for a moment at the half-landing, where the bathroom was, she decided to stop wondering about her father and to have a very hot bath.

2

Strictly speaking, the Culworths never had dinner. Their midday meal was lunch, and their evening meal, usually taken at about seven o"clock, was supper. And it was apt to be rather sketchy. Mrs Culworth was an indifferent caterer; Alan and his father would eat anything in an absent-minded way; and though Maggie knew better and liked good food – and Hugh Shire had taken her to some splendid West End restaurants during the three years she had been his mistress – the attitude of the other three made any effort look ridiculous. Supper that Monday evening consisted of macaroni cheese and peas, fruit salad and custard, and like her mother and her brother she mechanically consumed it. But, unlike them, she kept worrying about her father's absence. She had not expected Alan to share her anxiety. It wasn't rational, she knew, whereas Alan was nothing else but – and anyhow never really saw people as persons, only caring about figures and subatomic particles and moths and things.

Читать дальше