‘I decided that you would most probably be in a small institution in Alsace or Lorraine where German speaking patients would be natural; and probably only one person would be in the secret—the medical director himself.

‘To discover where you were I enlisted the services of some five or six bona fide medical men. These men obtained letters of introduction from an eminent alienist in Berlin. At each institution they visited the director was, by a curious coincidence, called away by telegram about an hour before the visitor’s arrival. One of my agents, an intelligent young American doctor, was allotted the Villa Eugenie and when visiting the paranoic patients he had little difficulty in recognising the genuine article when he saw you. For the rest, you know it.’

Hertzlein was silent a moment.

Then he said, and his voice held once again that moving and appealing note:

‘You have done a greater thing than you know. This is the beginning of peace—peace over Europe—peace in all the world! It is my destiny to lead mankind to Peace and Brotherhood.’

Hercule Poirot said softly:

‘Amen to that…’

xi

Hercule Poirot sat on the terrace of a hotel at Geneva. A pile of newspapers lay beside him. Their headlines were big and black.

The amazing news had run like wildfire all over the world.

HERTZLEIN IS NOT DEAD.

There had been rumours, announcements, counterannouncements—violent denials by the Central Empire Governments.

And then, in the great public square of the capital city, Hertzlein had spoken to a vast mass of people—and there had been no doubt possible. The voice, the magnetism, the power…He had played upon them until he had them crying out in a frenzy.

They had gone home shouting their new catchwords.

Peace…Love…Brotherhood…The Young are to save the World.

There was a rustle beside Poirot and the smell of an exotic perfume.

Countess Vera Rossakoff plumped down beside him. She said:

‘Is it all real? Can it work?’

‘Why not?’

‘Can there be such a thing as brotherhood in men’s hearts?’

‘There can be the belief in it.’

She nodded thoughtfully. She said:

‘Yes, I see.’

Then, with a quick gesture she said:

‘But they won’t let him go on with it. They’ll kill him. Really kill him this time.’

Poirot said:

‘But his legend—the new legend—will live after him. Death is never an end.’

Vera Rossakoff said:

‘Poor Hans Lutzmann.’

‘His death was not useless either.’

Vera Rossakoff said:

‘You are not afraid of death, I see. I am! I do not want to talk about it. Let us be gay and sit in the sun and drink vodka.’

‘Very willingly, Madame. The more so since we have now got hope in our hearts.’

He added:

‘I have a present for you, if you will deign to accept it.’

‘A present for me? But how charming.’

‘Excuse me a moment.’

Hercule Poirot went into the hotel. He came back a few seconds later. He brought with him an enormous dog of singular ugliness.

The Countess clapped her hands.

‘What a monster! How adorable! I like everything large—immense! Never have I seen such a big dog! And he is for me?’

‘If it pleases you to accept him.’

‘I shall adore him.’ She snapped her fingers. The large hound laid a trusting muzzle in her hand. ‘See, he is as gentle as a lamb with me! He is like the big fierce dogs we had in Russia in my father’s house.’

Poirot stood back a little. His head went on one side. Artistically he was pleased. The savage dog, the flamboyant woman—yes, the tableau was perfect.

The Countess inquired:

‘What’s his name?’

Hercule Poirot replied, with the sigh of one whose labours are completed:

‘Call him Cerberus.’

The Incident of The Dog’s Ball

In this story we have a recognisable, and in many ways, a typical Christie setting—a small village, a wealthy old lady and her avaricious relatives. It is immediately apparent, even from the title, that there are strong links to the 1937 novel Dumb Witness. She retains the basic situation and it is possible to see the germs of ideas that she expanded—the brief mention of the Pym spiritualists, the all-important accident on the stairs—into larger parts in the novel. But unlike some other occasions when she reused an earlier idea or short story (‘The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest’ for example), here she gives us a different murderer and explanation.

The plot device of Poirot receiving a plea for help from someone who dies before Poirot can talk to them is one that she had used on a few previous occasions. As early as The Murder on the Links (1923) his correspondent is already dead when Poirot arrives in France. Subsequently it is used in ‘How Does your Garden Grow?’ and ‘The Cornish Mystery’.

When was it written?

Of the Poirot and Hastings short stories, all with the exception of ‘Double Sin’ (September 1928) and ‘The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest’ (January 1932) were published in 1923/24. All the Poirot short stories after 1932 feature Poirot alone. No notes for any of those early stories survive and where Christie refers to them in the Notebooks, it is only as a reminder to herself of the possibility of expanding or reusing them. In many ways ‘The Incident of the Dog’s Ball’ is similar in style, setting and tone to many others dating from the early 1920s and published in Poirot Investigates and Poirot’s Early Cases. But if it was written early in Christie’s career, this in turn raises the question of why it would have lain for almost 20 years without appearing in print. It does not appear in her agent’s records of work received by them and offered for sale. I hope to show that it dates from later in her career.

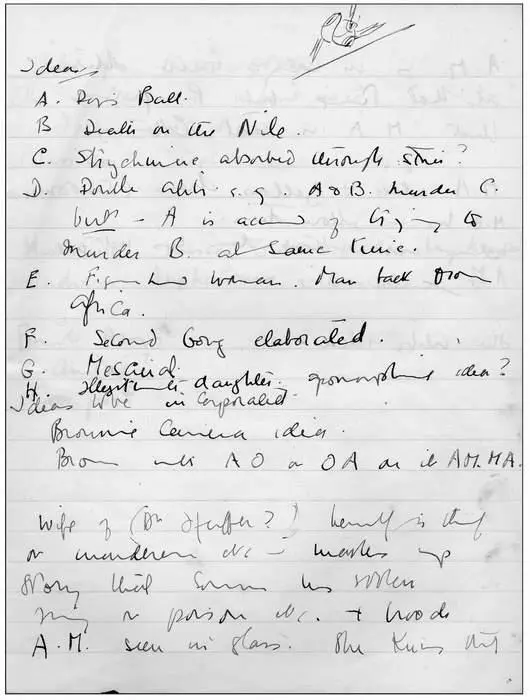

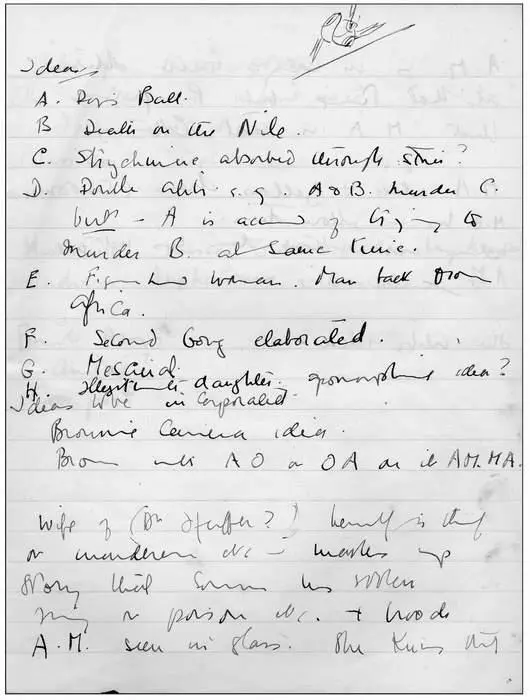

In Notebook 30 it is included in a list (illustrated on the jacket of this book) which may help us to establish more accurately its date of composition:

Ideas

A. Dog’s Ball

B. Death on the Nile

C. Strychnine absorbed through skin?

D. Double Alibi e.g. A and B murder C but—A is accused of trying to murder B at same time.

E. Figurehead woman. Man back from Africa.

F. Second Gong elaborated

G. Mescaline

H. Illegitimate daughter—apomorphine idea?

Ideas to be incorporated

Brownie camera idea

Brooch with AO or OA on it AM. MA

If we apply some of Poirot’s own methods we may be able to arrive at a timetable.

This page from Notebook 30 is part-transcribed on the opposite page. Note the three intertwined fish logo in the top right-hand corner.

Clue No. 1

There are a number of immediately recognisable stories here: Dumb Witness or ‘The Incident of the Dog’s Ball’ (A), Death on the Nile (B), They Do it with Mirrors (D) and Sad Cypress (H). ‘The Second Gong’ (F) was first published in June 1932 and both Dumb Witness and Death on the Nile in 1937, the former in July and the latter in November of that year. So it is reasonable to assume that the list was written between those dates, i.e. after ‘The Second Gong’ in June 1932 and before Dumb Witness in July 1937.

Clue No. 2

Unlike Item F on the list, ‘Second Gong elaborated’, there is no mention of elaboration in connection with ‘Dog’s Ball’, lending support to the theory that it did not then exist as a short story.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу