Last Scene

Ph and M are there—Angela comes in—then W—finally Lady D—M is a little dismayed. Caroline had motive—she had means—now to hand takes coniine and it seems quite certain she did take it—has questioned Meredith if person could handily take it if 5 people in room—but she was last and M in doorway had his back to room—so we take it as proved that she took it

Three Blind Mice (Radio Play 30 May 1947; Short Story 31 December 1948; Play 25 November 1952)

Three blind mice, three blind mice

See how they run, See how they

run They all ran after the farmer’s wife

She cut off their tails with a carving knife

Did you ever see such a thing a thing in your life

As three blind mice

Monkswell Manor Guest House welcomes its first visitors, including the formidable Mrs Boyle and the mysterious Mr Paravacini, as well as amusing Christopher Wren and enigmatic Miss Casewell. But Sergeant Trotter arrives to warn them of a potential killer in their midst, just before one of the guests is murdered.

As usual, Christie’s Autobiography is maddeningly vague about dates, so when she writes ‘About then the B.B.C. rang me up and asked me if I would like to do a short radio play for a programme they were putting on for some function to do with Queen Mary’, we must assume it was in 1946 as the ‘function’ was the eightieth birthday of Queen Mary on 30 May 1947. She duly presented them with Three Blind Mice, a half-hour radio play. The following 21 October it was broadcast as a 30-minute television play with the same name and script. She subsequently reworked it as a long short story, which appeared in a US magazine in 1948 and a UK one early in January 1949. It was collected, but only in the USA, in Three Blind Mice and other Stories in 1950. When the collection that ultimately appeared in the UK as The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding was in the planning stage, Christie made it clear that she did not want Three Blind Mice to be included as ‘masses of people haven’t seen it yet’ and she did not want to spoil their enjoyment.

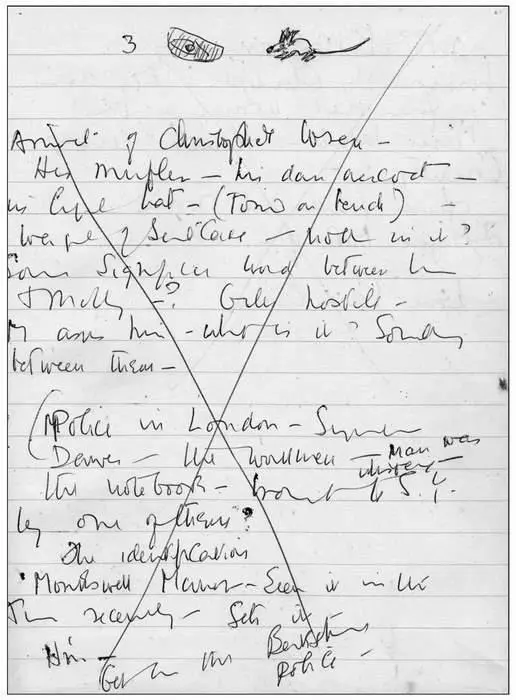

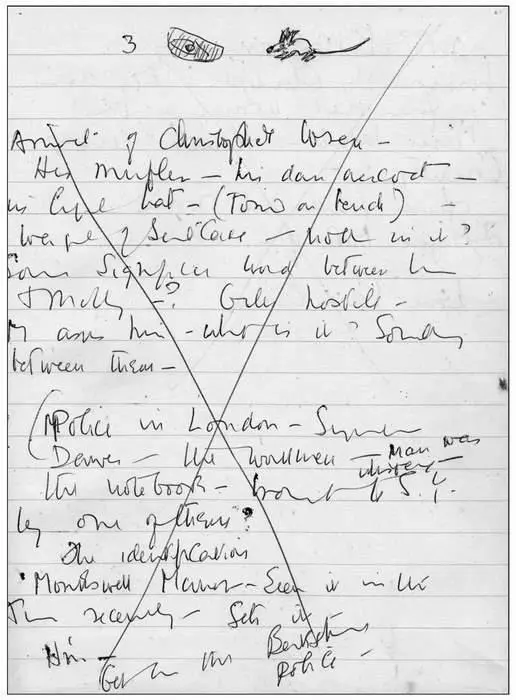

An amusing rebus in Notebook 56 heads the top of the first of only two pages to feature the most famous play in the world —Three Blind Mice ( later The Mousetrap).

In her Autobiography she continues, ‘The more I thought about Three Blind Mice, the more I felt that it might expand from a radio play lasting twenty minutes to a three act thriller.’ So she re-reworked it as a stage play, but when it came to presenting it a new title had to be found as the original was already the name of a play. Her son-in-law, the erudite Anthony Hicks, came up with The Mousetrap (from Act II, Scene ii of Hamlet ) and it opened in London on 25 November 1952. The rest is history…

The main changes between the different versions are in the very beginning. The radio and television versions feature the first murder, that of Mrs Lyon in Culver Street; the theatre version includes this only in sound effects on a darkened stage. The early draft of the script included an opening scene with two workmen sitting round a brazier who ask a passer-by for a match; the passer-by transpires to be the murderer on his way back from killing Mrs Lyon in nearby Culver Street and it is here that he drops the notebook containing the address of Monkswell Manor. Replacing this scene in the novella version is one set in Scotland Yard where the workmen describe the events of that evening.

There is almost nothing showing the genesis of this most famous work as a radio play. Notebook 56 does, however, have two pages headed, amusingly, 3 (an eye crossed out) (a mouse). As the following passage indicates, these few notes refer to either the novella or the stage version:

Arrival of Christopher Wren—his muffler—his dark overcoat—his light hat (throw on bench)—weight of suitcase—nothing in it? Some significant word between him and Molly. Police in London—Sergeant Dawes—the workmen—man was indistinct. The notebook—brought to S.Y. by one of them? The identification—Monkswell Manor. H’m—get me the Berkshire police. Mrs Bolton arrives—My dear, a formidable woman—very Memsahib

A reference to Christopher Wren’s suspicious suitcase appears in the novella, as does the ‘get me the police’ phrase; the combination of these two ideas would lend support to the theory that it is the novella version to which the Notebook refers. Also notable is the odd reference to Mrs Bolton rather than Mrs Boyle, the name by which she is known in every version.

Crooked House 23 May 1949

Charles Hayward falls in love with Sophia Leonides during the war and is fascinated by her family, who live together in a crooked house ruled over by her wealthy grandfather. When he is poisoned, it is obvious that a member of the family is crooked in the criminal sense.

Crooked House remains one of the great Christie shock endings. So shocking was it considered that Collins wanted her to change the ending ( Sunday Times interview, 27 February 1966), but she refused. It would be reasonable, therefore, to suppose that this solution was the book’s raison d’être. At least judging from the Notebooks we have, however, this was far from the case. As we saw in Chapter 3, several characters were considered as possible murderers before Christie arrived at the perfect solution.

In her specially written foreword to the Penguin ‘Million’ edition of Crooked House Agatha Christie writes: ‘This book is one of my own special favourites. I saved it for years, thinking about it, working it out, saying to myself “One day when I have got plenty of time, and want to really enjoy myself—I’ll begin it.” I should say that of one’s output, five books are work to one that is real pleasure. Writing Crooked House was pure pleasure.’

If, indeed, she spent years thinking and working it out, none of those notes have survived. Notebook 14, which contains most of the notes for this title, also contains, very exceptionally, two instances of dates. A few pages before the Crooked House outline the dates ‘Sept. 1947’ and ‘20th Oct [1947]’ occur. The novel first appeared in an American serialisation in October 1948 and was published in the UK in May 1949. From internal evidence (a reference to Aristide’s will being drafted ‘last year’ in November 1946) and from the evidence of the Notebooks below, the book was completed late in 1947 or early in 1948. So the years spent ‘thinking about it and working it out’ are, in all probability, those spent in the mental process before pen was put to paper. The more than 20 pages of notes cover the entire course of the novel.

The first page of notes in Notebook 14 is also headed ‘Crooked House’ so it seems to have been the title from the beginning. And, indeed, it is difficult to think of a better one. But (as we saw earlier in this chapter) Notebook 56 lists, on its opening page, the germ of A Pocket Full of Rye, which includes a distinct reference to a crooked house—although it is possible that the intention was to have a crooked, i.e. dishonest, businessman and no reference to the novel of that name is intended.

Sing a song of sixpence—the crooked sixpence found (a Crooked man Crooked wife Crooked house)

Coming home—Parlourmaid—maid and son—collusion—maid killed to prevent her telling

Some pages before starting the serious plotting of this title we find two references to it:

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу