York, situated on the tidal River Ouse (no longer tidal because of a dam), and halfway between Edinburgh and London, was considered the capital city of the north politically and financially through the 15th century. It was an important city to the Romans, who called it Eboracum and housed a legion there, to the Vikings, who called it Jorkvik and settled there, and to William the Conqueror, who burned much of it to convince the rebellious northerners that he was indeed King. He built twin castles to guard the river, York Castle on the east bank, and what is known as the Old Baile on the west bank.

As a crossroads, York became an important market town and trading center. Two rivers join to the south of the city walls, the Ouse and the Foss. Ouse Bridge, with its city council hall, city jail, St. William’s Chapel, maison dieu (hospital for the poor), public privy, and assorted other buildings, was the only bridge between the Ouse and the sea large enough for carts to pass over it. Upriver, a chain stretched between Lendal Tower and what is now called the North Street Tower to prevent the movement of ships without the payment of a toll. In the 14th century the York quays bustled with the wool trade that financed Edward’s war.

York was also an important ecclesiastical center. One must never underestimate the power of the Church in the 14th century. In York alone there were 10 religious houses, 47 churches, 16 chapels, and the cathedral. York was the seat of the second most powerful Churchman in England, the Archbishop of York. All of England was divided into two metropolitan provinces, Canterbury and York, which were further divided into dioceses (about 21). The Archbishops of Canterbury and York sat in the House of Lords, at this time known as the Great Council. The Abbot of the Benedictine monastery of St. Mary’s in York also sat on the Great Council. When Abbot Campian and Archbishop Thoresby discuss Owen’s inquiries over a flagon of wine, two great men are protecting their considerable interests.

In fact, they were lords of their own liberties in York. Although the city had a mayor and two councils, there were areas of the city under separate rule, called liberties. York Castle was one such liberty. Abbot Campian was lord of the liberty of St. Mary’s, and Archbishop Thoresby was lord of the liberty of St. Peter’s, or York Minster. A liberty represented an immunity from royal administration because the officials of the liberties, not the King’s officials, carried out royal orders. Each liberty had jurisdiction for crimes committed in it and contained its own courthouse, jail, and gallows. Hence the deaths at the abbey occurred in Abbot Campian’s jurisdiction, and Thoresby’s inquiries were intrusive.

But Archbishop John Thoresby was much more powerful than Abbot Campian because he was both Archbishop of York and Lord Chancellor of England, one of the chief officers of the state. This was not an unusual dual career. In fact, because archbishops and bishops were politically active, it was understood that they depended on their archdeacons to carry out most of their duties. York was divided into five archdeaconries: York, East Riding, Cleveland, Richmond, and Nottingham.

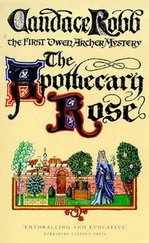

Writing a historical mystery novel requires the author to wear three hats, novelist, historian, and mystery writer. The novelist guards the integrity of the form, the growth of the main character, and glories in the creation of the character’s world, freely using the imagination. But the historian groans at anachronisms, agonizes over chronologies, and corrects descriptions according to archeological studies from city plans to the heights of the people. The mystery writer doesn’t want too much superfluous historical description to confuse the clues, has to postpone some of the revelations of the novelist in order to maintain suspense, and yearns to move things around in time and place to serve the mystery. Compromises must be made in order to finish the book in one’s lifetime.

I have chosen not to dwell on the filthy, unsanitary conditions in 14th century York, how narrow the streets were, how dark because of the overhanging upper stories. Owen notes that it stinks like Calais and London when he first enters the city, and wonders why anyone would live there. But the rest of the characters are residents of York and would take no more notice of the conditions than we do of our own cities. To the city dwellers, the much discussed filth of the medieval city was like our modern day pollution, something that was part of urban life.

I chose York as the base for my series character because of its varied importance in the period. I made Owen an outsider because the best detectives have been people outside the immediate society, never quite a part of the community, and because his past experiences and connections would make him more flexible. A Welsh archer who climbed so high in the household of the Duke of Lancaster would be intelligent and resourceful. And, of course, physically strong.

I had similar motives of isolation and flexibility in creating Lucie Wilton’s situation. I wanted her to be as independent as a woman could be in the Middle Ages, and a strong woman so unlike the court and camp women Owen had known for so many years that he must go all the way back to memories of his mother to have a clue to how to please her. She is an ambitious woman, and one much like Queen Elizabeth I who learned in childhood that a woman must learn to count on herself. Unfortunately, apothecaries did not become regular members of a guild in York until the 15th century, when they appear on the rolls of the Merchants’ Guild. Guilds developed differently from city to city. In Paris, apothecaries were part of the Brewers’ Guild. And in 14th century Paris, Lucie might very well have taken over the shop at her husband’s death. So the novelist used Paris guild rules in York, but the historian made sure they were historically accurate rules. The mystery writer made Lucie a woman outside the hierarchy, the daughter of a lord but the wife of a master apothecary, with a troubled past and the skill and ambition to make her satisfactorily suspicious.

Most of my characters are fictional, but the old Duke, Henry of Lancaster, was indeed a powerful military hero who died in 1361. John of Gaunt, third son of King Edward III, did become Duke of Lancaster on Henry’s death. John Thoresby was both Lord Chancellor of England and Archbishop of York, although he had resigned his post as Lord Chancellor by 1363. I postponed his resignation in order to consider the two sides to such a statesman/Churchman, a common coupling in medieval England. In this book he is still comfortable with his dual role, but later he will find it intolerable. Archdeacon Anselm is my own creation. His obsessive character was necessary for the story.

And what of the Digbys? Chaucer sketched a sordid, unlikable Summoner in The Canterbury Tales . What kind of person chooses a career as a snoop? Owen sees an unpleasant similarity between his job and Potter Digby’s. But Digby saw the post as a legitimate way to climb out of the vermin city that clustered on the ever flooding river bank north of the abbey walls. The Ouse still floods after winter storms up on the moors. In December of last year I woke one morning to discover that the riverside street below my townhouse was a frozen lake. Overnight, the river had risen several feet. In the morning, as the day dawned sunny and cold, the lake froze. When the river receded, frozen, rutted mud remained. Gradually it thawed into a muddy mess. What must it have been like in the 14th century, when your house was mud and sticks?

Magda Digby, Potter’s mother, lives in a world of her own. An old Viking boat from York’s past crowns her house. Her speech is the old speech. Magda is purely the novelist’s creation, and perhaps to me the character most real. Like the juxtaposition of pagan and Christian England in Beowulf , Magda encapsulates the past and present. She is outside time, like the city of York, part Roman, part Viking, part medieval, part Victorian, part 20th century tourist town. And therein lies the intrigue.