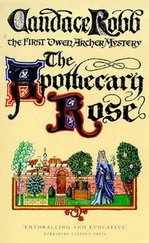

“That is what he says. But what do you think, Your Grace?”

Thoresby smiled. He liked her. “I believe him. And I think he was done with killing. He lost that eye because he saved someone’s life who did not find his life anything to be grateful for. Archer is an innocent. Was. I think he has learned something in my service.”

“He saved my life.”

“It’s fortunate that Archer still has the reflexes of a soldier, if not the heart. God be with you, Mistress Wilton.”

“You will not punish him for your Archdeacon’s death?”

Another odd question. “I did not become Archbishop of York and Lord Chancellor of England by being a fool, Mistress Wilton.”

Lucie sat long into the evening. Melisende came in, drank some water, napped in Lucie’s lap, Tildy put food before Lucie and took it away cold, Bess looked in and decided to leave her in peace, the cat left for her night revels, and at last, cold and stiff in all her joints, Lucie dragged herself up to bed, where she buried her head and wept.

Owen tossed on his cot, holding his ears. But still he heard the bells, felt them vibrate through his body. Damnable bells.

A timid knock. “Pilgrim Archer. It is time for the Night Office.”

Owen sat up, realizing why the bells had sounded so loud. He was at St. Mary’s. He groped for his eye patch, put it on, and opened the door of his cell.

A novice bowed to him. “Follow me.”

The bells stopped. In the echoing silence, his and many other sandaled feet whispered along the dimly lit stone corridors. The black-robed company filed into the candlelit chapel and flowed into the rows of seats, all without speech, with few even looking up. The novice led Owen to his place. He looked round at his companions, most with their hoods up, heads bowed, no one bristling with resentment, no one jostling for a better seat. All these men moving with humility and quiet obedience. It filled Owen with a sense of peace. In this he could see the appeal of monastic life. As they began to chant the office, he felt lighthearted.

Until his eye rested on Brother Wulfstan. Gentle Wulfstan. Since the attempted poisoning, there was a vague cast to the old Infirmarian’s eyes, as though his thoughts were fixed on the next life. Owen wondered how long Michaelo’s poison would linger in Wulfstan’s body, and whether the novice Henry had thought to bleed the old monk.

Owen’s feeling of peace was gone.

After he had broken his fast the next morning, Owen wandered to the infirmary to speak with Henry. But he found Wulfstan alone at his worktable, dripping various essential oils into a salve paste. As each oil touched the warm paste, it released its intense perfume. Owen understood why the old monk stood near a slightly opened window.

“May we speak?” Owen asked. He was not sure how closely they followed the Rule of Saint Benedict here.

Wulfstan motioned Owen to a seat near him. “The infirmary is necessarily an exception – and, as our Savior knows only too well, I have grown lax in my vow of silence over the years.”

This morning the old monk’s eyes looked clear. “You seem much recovered,” Owen said.

Wulfstan thought a moment, then nodded. “A bad business. Who would have thought Michaelo would do such a thing?” He gave a little laugh. “I find it quite miraculous that he had the energy.”

The laughter surprised Owen. “You have forgiven him?”

Wulfstan shrugged. “He has confessed and performed penance.” He squinted while he measured another drop. “And if in his heart he truly repents, the Lord God will forgive him. I can do no less.”

“And Nicholas Wilton. Do you forgive him?”

Wulfstan sighed, wiped off his hands, sank down beside Owen. “That is more difficult. He used me to poison my friend. Abbot Campian explained that it was because Nicholas feared Montaigne. But he need not have done, of that I am certain. Geoffrey had come to make his peace with God. He would not have put his soul in peril. He would not have attacked the Wiltons.” Wulfstan brushed tears from his eyes.

“I am sorry for the pain this has caused you.”

The Infirmarian studied Owen’s face. “I believe you. I did not like you at first.”

“I know.”

“You knew too much for a stranger. Asked too many questions.” The old monk shook his head. “Poor Lucie. Will the story be told? Will she lose all that Nicholas tried to give her?”

“The Archbishop has no desire to publicize a scandal involving his late Archdeacon. But whether he will let Mistress Wilton keep the shop, I do not know.”

“You do not approve of the Archbishop’s silence?”

“I am pleased for Mistress Wilton. And for you. But the people have been misled about Anselm.”

Wulfstan shrugged. “He was a benighted soul. As are we all, more or less. Let him rest in peace.”

Owen was quiet.

“What will you do now?” Wulfstan asked.

“I would like to continue as Mistress Wilton’s apprentice.”

Wulfstan sighed. “I see.” Owen would bide his time, work his charm, ask for her hand. And who could blame him?

Early one morning two weeks after the funeral, Lucie woke to a fresh scent that reminded her of spring. She smiled when she turned toward the garden window and saw the quince branches she had brought in two days ago. The warmth in the room had coaxed them into bloom. A good omen on her first waking in this bed alone. She had dreaded this first night. She had put it off, sleeping in the smaller room with her Aunt Phillippa while they aired out this room and scrubbed away the illness and death.

Phillippa had left the day before, with misgivings. “I should not leave you so soon. You have not even tried a night in the room they died in. Some people find it frightening. Though Heaven knows, others must have died here before Nicholas and Anselm. It is knowing it. Having seen Nicholas here in his shroud–”

“Please, Aunt Phillippa.” Her constant chatter would drive Lucie mad. “You have been here when I needed you most. I can tell you’re worrying about Sir Robert and Freythorpe. A fortnight is long enough to be gone.”

Phillippa sighed. “You do seem to have things under control.” She looked round the tidy kitchen with satisfaction.

Lucie smiled. It was Phillippa and Tildy, not she herself, who had thoroughly cleaned the house. “I am sure that Tildy will keep this room clean now you’ve trained her.”

Phillippa straightened a bench. “She’s a good girl. Your Guildmaster has done right by you.”

“And the Archbishop.”

“Hmpf. It was in his own interest to keep silent about the matter. I would not waste too much gratitude on him, child.”

“Will you tell Sir Robert about Nicholas and Geoffrey?”

“I have prayed over that. I fear it might send Robert off on another pilgrimage. But I think he ought to be told. Who knows? A sense of the circle closing might wake him up to the world again. He might even think to come see his daughter.”

Lucie thought of that this morning, and did not know how she felt about the prospect. She had banished Sir Robert from her thoughts fifteen years ago. And before that he had been more of an ogre than a parent.

But the thought of him and Aunt Phillippa at Freythorpe Hadden, thinking of her, made her feel less alone.

She had never been so alone. As a child she had slept with her mother or her aunt. At the convent she had shared a room with other girls. And then she had come to Nicholas’s bed. Suddenly she was all alone. And would be so indefinitely.

Dreary thoughts. Perhaps Phillippa had gone too soon. But Owen was to return from St. Mary’s today.

Owen. The thought of his return cheered her. Silly. She could hardly expect him to keep up the ruse of apprenticing to her. Some pilgrim to the abbey may have offered him a post already. He might not even stop in to say good-bye.

Читать дальше