Owen accepted the proffered cup and tasted the wine. He had not tasted better, even at the old Duke’s table. The Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York treated him nobly. Owen could not think what he might want.

John Thoresby leaned back in his chair. He sipped his wine with quiet pleasure. A fire crackled beside them in the hearth that warmed the private anteroom. Tapestries caught the firelight and lent the warmth of their vivid colors to the room.

With his one eye, Owen could not look at the tapestries without being obvious. It required turning the head this way and that, especially for those on the left. There was only one solution. Be obvious. Praise the man by praising his possessions. He turned his head, letting his one eye span the room. A boar hunt began to the left of the door and continued around the room, finishing with a feast in the great hall, where the beast’s head was presented to the victor. The separate tapestries formed a complete set, designed for this room, for the fit was perfect. “The tapestries are exquisite. Norman work, I think. The close weave, the deep green. Norman for certain.”

John Thoresby smiled. “Not all your time in Normandy was spent on the battlefield, I see.”

“Nor yours in negotiations.” Owen grinned. He must not seem cowed by the honor of sharing wine in the Lord Chancellor’s chambers.

“You are a bold Welshman, Owen Archer. And adaptable. When the old Duke asked that I take you into my service, I thought his mind muddled with pain. He did not die with ease, as you may know.”

Owen nodded. Lancaster had died in agony. Master Roglio said the old Duke’s own flesh devoured itself from within so that he could at the end consume nothing but water, which exited his body as a bloody flux. Owen was moved that in the midst of his agony his lord had remembered him.

“He trained you to listen, observe, and retain.” Thoresby watched Owen over the rim of his cup. “Is that correct?”

“Yes, my lord.”

“So much trust might have overwhelmed an ordinary archer.” Thoresby kept his eyes steady on Owen.

The Archbishop was easy in himself. Honesty would be Owen’s best ploy. “I lost the sight in one eye, which I thought was death to me. My lord’s trust lifted me up from despair. He gave me purpose when I thought I had none. I owed him my life.”

“Owed him.” Thoresby nodded. “And you owe me nothing. I merely consider honoring an old comrade’s request.”

“You might have ignored it, and only God would be the wiser.”

Thoresby cocked an eyebrow. A grin danced on his lips. “The Archbishop of York would deceive a man on his deathbed?”

“If he judged that it were better for the soul in his care.”

Thoresby put down his cup and leaned forward, hands on knees. The Archbishop’s ring shone on his finger. The chain of Chancellor glittered in the firelight. “You make me smile, Owen Archer. You make me think I can trust you.”

“As Archbishop or Lord Chancellor?”

“Both. The matter concerns York. And two knights of the realm, dead before their times, in St. Mary’s Abbey. Do you know the abbey?”

Owen shook his head.

“Good. I want someone who can be objective. Make inquiries, note the facts, report them to me.” The Archbishop poured himself more wine and gestured for Owen to do the same. “We serve ourselves. I wished to have no ears but ours this evening.”

Owen poured himself more wine and sat back to hear the story.

“I must tell you that the new Duke of Lancaster is interested in you. You might do well with Gaunt. It would be a secure future – more so than with me. Mine are elected positions; he is the son of the King, and Duke of Lancaster for life. I tell you this because you might have cause to speak with him. The second knight in this matter was one of Gaunt’s men.”

Owen considered this wrinkle. Gaunt was dangerous, noted for his treachery. Owen could well imagine the sort of work Gaunt would give him. To serve him would be an honor, but it would not be honorable. Not to Owen. Surely God had not raised him up from the ashes for such work.

“I am flattered that two such powerful men offer me employment, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity to choose. But I prefer to serve the Archbishop and Lord Chancellor. I am better suited to your service.”

Thoresby cocked his head to one side. “Not ambitious, I see. You are a freak in the circles in which you dance at present. Beware.” His look was serious, almost concerned.

A shower of pain rushed across Owen’s blind eye, hundreds of needle pricks, hot and sharp. He’d taken to accepting these attacks as warnings, someone walking on his grave. “I am a cautious man who knows his place, my lord.”

“I think you are, Owen Archer. Indeed.” Thoresby rose, poked the fire for a moment, returned to his seat.

Owen put down the wine. He wanted a clear head.

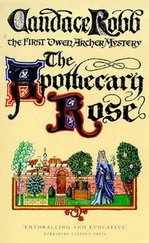

Thoresby, too, set aside his cup. “The puzzle begins thus. Sir Geoffrey Montaigne, late of the Black Prince’s retinue, makes a pilgrimage to York to atone for some past sin. We do not know what sin, for while in the service of the Prince, Montaigne’s behavior was beyond reproach. Something in his past, perhaps. Before joining the Prince’s army he fought under Sir Robert D’Arby of Freythorpe Hadden, a short ride from York. Montaigne’s choice of St. Mary’s at York for his pilgrimage suggests that his sin was linked to his time in D’Arby’s service. So. He arrives in York shortly before Christmas and within a few weeks falls ill of camp fever – the ride north jarred open an old wound, which weakened him, causing a recurrence of the fever he’d suffered in France – all this according to the abbey Infirmarian, Brother Wulfstan – and within three days Montaigne is dead.”

Thoresby paused.

Owen saw nothing odd in the story. “Camp fever is often fatal.”

“Indeed. I understand that after you were wounded you assisted the camp doctor. You treated many cases of fever?”

“Many cases.”

“Master Worthington praised your compassion.”

“I’d had the fever myself but a year before. I knew what they suffered.”

The Archbishop nodded. “Montaigne’s death would have gone unremarked but for another death at the abbey within a month. Sir Oswald Fitzwilliam of Lincoln, a familiar face at the abbey, making retreats for sins that were only too easily guessed at by all who knew him. Shortly after Twelfthnight he falls ill with a winter fever. It worsens. He sweats profusely, complains of pain in his limbs, has fainting spells, fever visions, and within a few days he is dead. A similar death to Montaigne’s.”

“A similar death? But it does not sound like camp fever.”

“Toward the end, Montaigne was much the same.”

“The Infirmarian poisoned these men?”

“I think not. Too obvious.” Thoresby took up his cup and drank.

“Forgive me, Your Grace, but how do you come into this?”

The Archbishop sighed. “Fitzwilliam was my ward until he came of age. An embarrassing failure for me. He grew to be a greedy, sly creature. I used all the weight of my offices to get him into Gaunt’s service. I did not make friends in doing so. I assume my ward was poisoned. And though I do not pretend to mourn him, I should know his murderer.”

“And Montaigne?”

“Ah. As far as I can determine, a God-fearing man with no enemies. Perhaps his death is unrelated.” The Archbishop leaned back and closed his eyes. “But I think not. The deaths were too similar.” He looked up at Owen. “Poisoned by mistake?” He shrugged. “Or was he merely better at burying his business than Fitzwilliam?” He smiled. “And here’s an interesting item. Montaigne did not give his name at St. Mary’s. He called himself a pilgrim. Humble and plain. Or sly?”

Читать дальше