Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catilina's riddle

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catilina's riddle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catilina's riddle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Catilina's riddle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catilina's riddle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'I wanted you to see for yourself, Master,' he said, 'so that there would be no misunderstanding later.'

'See what?'

He indicated a bundle of dried grass. His jaw was clenched, and I saw a twitch at the corner of his mouth.

'I see nothing wrong,' I said, 'except that this bale of hay has been cut open, and these men are standing around when they should be bundling the rest.'

'If you will look closer, Master,' said Aratus, bending towards the open bale and indicating that I should do likewise.

I squatted down and peered at the mowed grass. My vision at a near distance is not what it once was. At first I did not see the grey powder, like a fine soot, that spotted the hay. Then, having perceived it, I saw mottled patches everywhere within the bale.

'What is this, Aratus?'

'It's a blight called hay ash, Master. It appears every seven years or so; at least, that's my experience. It never manifests itself until after the grass is mowed, and sometimes not until much later, when a bale is cut open in the winter and you find out that the hay within is black and rotted.'

'What does this mean?'

'The blight makes the hay inedible. The beasts will not touch it, and if they do, it will only make them sick.' 'How extensive is the damage?'

'At the very least, all the grass within this field is almost undoubtedly ruined.'

'Even if there is no blight on the blades?' I looked around at the mowed grass and saw no sign of the sooty spots.

'The blight will appear in a day or two. That's why it's often not seen until the winter. The hay is already bundled when the blight appears. It works its way from the inside out.'

'Insidious,' I said. "The enemy within. What of the other fields? What of the hay already baled and stored?'

Aratus looked grim. ‘I sent one of the slaves to cut open one of the first bales, from the field up by the house.' He handed me a blade of hay covered with the same grey soot.

I gritted my teeth. 'In other words, Aratus, you're telling me that all the hay is ruined. The whole crop that was meant to sustain us through the winter! And I suppose this has nothing to do with the fact that you waited so long to cut the grass?'

'The two things are unrelated, Master—'

'Then if the grass had been mowed earlier, as I wanted, this blight would still have found its way into the hay?'

'The blight was there before the mowing, unseen. The time of mowing and the appearance of the blight have no connection—'

'I'm not sure I believe you, Aratus.'

He said nothing, but only stared into the middle distance and clenched his jaw.

'Can any of the hay be saved?' I asked.

'Perhaps. We can try to set apart the good and burn the bad, though the blight may keep appearing no matter what we do.'

"Then do what you can! I leave it to you, Aratus, since you seem to think you understand the situation. I leave it to you!' I turned around and left him standing there among the other slaves while I stalked across the shorn fields, trying not to calculate the waste of time and labour that had given me fields upon fields of hay that was good for nothing but kindling.

That afternoon great plumes of smoke rose into the still air from the bonfires which Aratus organized in the fields. I went myself to make sure that only the visibly blighted hay was being destroyed and found bales that appeared to be untouched mixed among the kindling. When I pointed this out to Aratus, he admitted the error, but said that saving any of the hay was only a postponement. I found this a poor excuse for destroying hay that might, for all I knew, be perfectly good. I had only Aratus's word and his judgment that the good hay would yet be blighted. What if he was mistaken, or even lying to me? A fine thing that would be, to be deceived into destroying a whole crop of good hay on the advice of a slave in whom I was beginning to lose all trust.

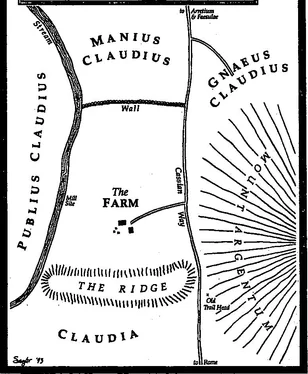

Plumes of smoke continued to rise into the air the next morning, when Aratus separated more bales of blighted hay and made them into bonfires. Not surprisingly, a messenger arrived from Claudia. The slave was shown into my library, bearing a basket of fresh figs in his arms.

'A gift from my mistress,' he explained. 'She is proud of her figs and wishes to share them with you.' He smiled, but I saw him glance sidelong out the window at the pillars of smoke.

'Give her my thanks’ I called to one of the house slaves to fetch Congrio, who seemed a bit startled at being summoned so early in the day. He gave Claudia's messenger an odd look, which made me think something untoward must have transpired between them during his stay at her house; slaves are always fighting with one another. 'Congrio,' I said, 'see the fine figs Claudia has sent to me? What might we send her in return?'

Congrio seemed to be at a loss, but at last suggested a basket of eggs. "The hens have produced an exceptional batch of late,' he assured me. 'Yolks like butter and whites that stir up like cream Fresh eggs are always a treasure, Master.'

'Very well. Take this man to the kitchens and supply him.' As they were leaving the room, I called for the slave to come back. 'And in case your mistress should ask,' I said in a confidential tone, 'the plumes of smoke she sees rising above the ridge come from a blighted crop of hay. Hay ash, my steward calls it. She may tell this to the other Claudii if they come asking her, as I doubt that they will send messengers onto my property to inquire for themselves.'

He nodded in the same confidential manner and withdrew with Congrio. Supplying him with eggs should not have taken long, but even so it was at least an hour later when I happened to be strolling around the house and saw him stepping outside through the kitchen door, holding a basket full of eggs and whispering something to Congrio over his shoulder. When he turned towards me, I saw the reason for his tardy departure, for he reached up with one hand to wipe a bit of custard from his lips. Who could resist tarrying for a while to sample a bit of Congrio's cooking? The slave saw me and gave a guilty start, then recovered himself and departed with a crooked smile.

The next day I had more evidence of Aratus's incompetence. Near the end of the day, when I escaped to the ridge to brood in solitude over the loss of the hay, I saw a wagon drawn by two horses turn off the Cassian Way. The heavily loaded vehicle lumbered along the road, sending up a small cloud of dust, and finally stopped alongside the house, near the kitchens. Congrio emerged from within and began to oversee the unloading of the wagon.

And where was Aratus? It was his job to oversee such work. I made my way down the hillside and came upon Congrio huffing and puffing as he helped his assistants unload heavy bags of millet and wooden crates stacked with clay cooking pots. The afternoon had cooled a bit, but Congrio was drenched with sweat.

'Congrio! You should be inside, tending to the kitchens. This is work for Aratus.'

He shrugged and made a face. 'I only wish that were so, Master.' He spoke with an anxious stutter, and I could see that he was as upset as I was. ‘I have asked Aratus over and over to order certain provisions for me from Rome — you simply cannot get such clay pots anywhere else this side of Cumae. He kept promising he would do so, but then he always put it off until finally I ordered the things myself. There was adequate silver in the kitchen accounts. Please don't be angry with me, Master, but I thought it best if I took the initiative and avoided confronting him in your presence.'

'Even so, it's Aratus who should oversee the unloading. Look at you, as red as a clay pot and sweating like a horse after a race. Really, Congrio, this kind of exertion is too much for you. You should be inside.'

'And let Aratus drop a crate and ruin my pots from spite? Please, Master, I can oversee the work myself I prefer it that way. The sweat is only the price I pay for carrying a bit of extra girth; I feel quite fine.'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catilina's riddle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.