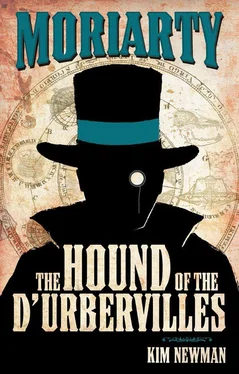

Kim Newman - Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kim Newman - Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was not fool enough to plop through the hole, and get a knife in my ribs for my pains.

There was a porthole above the controls, offering a glow like a skylight. I made my way there, inch by thorny inch. I didn’t let my head show, but got a glimpse below. The spy master was throwing switches and pulling levers. Electric lights burned. Dials came to life. He was getting his engine running before decoupling the rest of the train.

He kept looking around, alert.

I rose to a crouch, struggling to keep balance. The rushing wind would blow me off the roof if I presented too broad a back. Keeping steady, resisting an impulse to go too quickly, I stood. I let seconds pass, to get used to the slipstream. I took out my revolver and aimed at the porthole.

I fired, then stepped into the hole I’d made.

I intended to drop neatly down into the cabin in a rain of glass.

Instead, the train’s impetus slammed me into the rim of the porthole at waist height. Jagged glass shards ripped through my coat. I fell badly, on top of the ringer.

He got a knife — something small, like a scalpel — in my side, but I smashed my revolver-butt into his nose. It squashed and bled. I didn’t know how badly I was stuck, but got up off him. I kicked the shadow man several times, in the head and kidneys. He rolled away from my boots, and sprang up — agile as a big cat.

I shot him in the chest again, knowing it wouldn’t kill him. At close range, the impact must have broken some ribs. He yelled and fell again.

I saw the wedge — a wrench — that was keeping the door to the compartment shut, and kicked it free.

‘In here,’ I called to the Moriarty brothers.

I hauled the ringer up, took away his knife, and put my gun to the soft part under his chin. No chain mail there. Give him credit, he was already recovering from the equivalent of a sledgehammer blow to the chest. He was scouting for new means to vex me.

The Professor, the Colonel and the Stationmaster entered the cabin. The space was not really large enough to accommodate us all.

‘Why haven’t you killed him?’ the Colonel asked.

‘Can you drive a train, James?’ I said.

‘No.’

‘Can you, James, or you, James?’

Twin headshakes.

‘Then we need him alive, for the present. Can any of you at least decouple this locomotive?’

‘That’s simple,’ the Stationmaster said.

Young James took the loose wrench and used it to open a hatch in the floor. He twisted a lever below. There was a ripping sound, as plates parted. We were free of the rest of the Kallinikos, but still travelling in the same direction — fast.

On a slight incline towards the bridge which wasn’t shut, we gained speed and pressed against the other carriages.

I looked into the shadow man’s angry eyes. ‘Now, chummy,’ I said, ‘do you still want to be an engine driver when you grow up?’

I slightly relaxed the pressure on the pistol, without taking it away.

For a moment, I thought I’d misjudged the man. Plenty would die rather than give in. Some players see mate in two moves and kick over the board. I’ve never found out if I’m that sort myself, but rather think I am. If I’d been the one who knew how to drive the train, I’d have laughed at me and double-dared me to shoot my head off.

This was a more calculating person.

Someone more like the Professor. Cold-blooded, but practical.

Without saying anything, he rose and turned to the controls. A charge had built up in the batteries. I saw dynamos and what-nots whizzing. Acid bubbled in tanks. My impression was that all he had to do was engage this engine — whatever that meant — and we would be away.

The Kallinikos came out of the deep cutting and, miraculously, held to the rails as they took a gentle curve down a hillside towards the Ross Gorge. The other head smashed through a white wooden pole which hung across the line as a warning that the swing bridge was open.

‘Toot-toot,’ I said, darkly.

The shadow man threw a lever. A whistle did sound — not steam, but some indicator that the engine was working. Our wheels screamed as they were forced to turn the other way.

The rest of the train parted from us.

Through the open door which had lead into the previous carriage, now separated from our engine, I saw the rails leading to the edge of the precipice. Our lights showed what awaited us. Below was the River Ross. Not a raging, foaming torrent but a placid waterway. Ahead, useless, was the middle-section of the bridge, turned sideways on its pillar in the middle of the river.

The gap widened, but we were still travelling the wrong way.

If I shot the ringer now, it wouldn’t make any difference. On balance, I decided I’d rather what happened to me happened to him, too.

The front engine breasted the edge, dragging its carriages — which twisted, flame-nozzles pointing upwards — into the air. The Kallinikos was going at such speed I thought briefly that it might leap the gap, but the bridge-section was in the way. The worm’s head smashed against the pillar, and the whole contraption fell into the Ross with a scream of metal…

…there was an explosion, which left spots in my eyes for months. All the Greek Fire in the belly of the worm went up at once. A patch spread across the water like a floating island of flame.

I assumed we were going to fall into that.

But we slowed. The rails complained.

The brothers Moriarty held fast to canvas straps.

Through the open door, I could count the number of sleepers between us and the edge.

Then, there were half as many…

Then, none. Our wheels, I fancy, touched the lip of the gorge as we slowed to a stop. We all lurched, and Stationmaster Moriarty fell towards the door. Neither of his brothers tried to haul him back, but he got hold of the folding isinglass and didn’t tumble into the burning river.

The engine still ran. The wheels got traction.

And we changed direction, drawing away from the drop.

The sleepers appeared again. The gorge receded. Without the rest of the train as an anchor, we got up speed quickly. We were back in the cutting, rolling towards Fal Vale.

With another gun-prod, I persuaded our reluctant pilot to moderate our speed. A fatal crash now would be beyond irony.

‘How about a toot of the whistle,’ I suggested.

He made no comment.

‘Next stop, Fal Vale Junction,’ I said, light-headed. ‘All change yurr… ’ [45] The Fal Vale swing bridge was the site of a later, famous railway disaster — which gave rise to another ghostly legend. See: Arnold Ridley, The Ghost Train, St Martin’s Theatre, 1923.

IX

The surviving head of the Kallinikos rolled into the station. I took care to watch the pilot as he threw the brakes and prodded him as he turned off the engine. A series of switches had to be thrown in sequence. The drone of the dynamos died.

Colonel Moriarty was trying to issue orders again. No one listened. Most of the folk who would have snapped to when he told them had gone into the river with the tail of his wonderful war-worm. The Department of Supplies wasn’t an easy, safe commission any more. In the Colonel’s coming wars, even file-clerk and engine-maintenance soldiers would be asked to pay the butcher’s bill.

At Fal Vale, the fighting was over.

There was some precariousness in getting out of the engine. There was no side door, just an egress to the rest of the train… so, the Moriarty brothers had to clamber down onto the rail bed and then make their way up onto the platform. They could have walked to the far end of the station, and taken the gentle slope up, but Young James pulled himself up to the platform, tearing his uniform at the knees, to show how limber he was. After that, his older brothers grimly followed suit, despite aged bones, tight waistcoats and a seeming unsuitability for such physical action. The Colonel grunted, went red in the face as he lifted his feet off the rails, and had to be pulled up by Stationmaster Moriarty and Berkins. He lost some buttons, and the last vestiges of his commanding manner.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)