Beats, like a galloping horse. It was coming fast and low, without regard for itself or us.

Another howl sounded, shrill and close and mocking, off to one side. Not from the onrushing creature.

I looked to the howling, bringing my aim round.

We were in The Chase with more than one beast.

I swung back to the more imminent threat, just as some big, black — not red! — and shaggy quadruped burst into the clearing, barrelling like a bull, snorting like a hog, foaming like a mad dog. I fired true and placed a shot in its skull. Momentum kept the thing coming. What was it? Venn whacked with his stave, which was snatched from his hands. I cleared my breech and reloaded. The Albino’s guns went off, blasting fist-sized red gobbets out of a woolly hide.

The howling kept up. I didn’t fire again. This might be a tactic to get us to waste our shots.

‘It’s Old Pharaoh,’ shouted Saul.

It must be dead or dying, but still it tore around, head down, butting at us. Venn, off his feet, slammed into me. I fell backwards into damp mist and put out my hand — which jammed painfully against cold rock. I fell onto Scary Face Stone. My rifle hit me in the face.

‘Git Priddle’s prize black ram,’ Saul explained.

I recalled the beast, which Priddle claimed was taken by Red Shuck. Stoke suspected Old Pharaoh was hidden from his tally-man, so the farmer could duck out of paying tax due.

Through agitated mist, I saw the ram was as big as some lions I’ve shot, humped like a buffalo, with curls of battered, hardened horn. Blood leaked from the hole I’d put in its bulbous forehead. Life was gone from saucer-sized eyes, but it took long moments for the message to reach the body.

Then, Old Pharaoh fell, dead.

Outside Temple Clearing, the howling abated.

I groped in the mist for my gun. Saul waded towards me — to help? His boot came down on my bare hand, crushing it against Scary Face Rock. Two or three fingers broke. Pain rushed up my arm.

I swore.

Saul tried to apologise. I kept swearing, at the pulsating hurt as much as the blundering idiot. Saul took me by the shoulders and helped me get my balance. I found the rifle on the ground, but agony hit again as I made a fist to pick it up.

I raised the gun in a rough aim, but could no more fit my snapped trigger-finger into the guard than you could thread a needle with a sausage. I threw the rifle down. My revolver was slung for a cross-draw. I had to reach into my coat and fish the gun out of my armpit with the wrong hand.

I laid against a bleeding wall of mutton, as if the dead ram were a pile of sandbags. Venn was beside me.

‘Sheep be driven,’ he said. ‘By a dog.’

I’d worked that out by now.

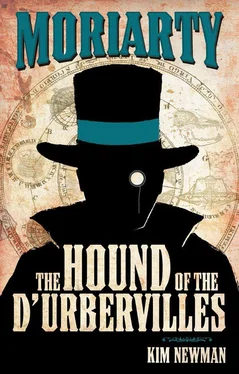

Even though we’d all suspected human agency behind Red Shuck, no one at Trantridge — including yours truly — had thought it through. With my hand swollen and useless and the smell of just-dead sheep in my nose, I had a moment to wonder whether Moriarty had seen the truth and not troubled to mention it. It was the manner of smug trick he was given to, a refined version of his testing via sudden missile or sharp question.

From Stoke’s story, I’d pictured a canny malcontent importing or discovering or raising some unknown species of canine and letting it prey on whom it might. This feint with Old Pharaoh bespoke more active agency. Our as-yet unknown enemy had Red Shuck trained as a sheepdog. Doubtless, the doggie was tutored in amusing tricks — fetch out the fellow’s throat, jump up and bite, roll over and kill. In Wessex, it wouldn’t even take a mastermind. A half-skilled shepherd could manage the trick, and the region was thick with the bastards. If I survived the afternoon I’d call on the Priddle hovel with harsh questions for a well-known ram-withholder.

I was still trying to make a fist, to control the knot of pain at the end of my arm.

Venn coughed blood. It smeared his chin, matching his skin. Even his teeth were red.

Saul, in the centre of the clearing, shrugged off his sample-bag, ears pricked. The Albino was by him, reloading. Besides Old Pharaoh, he had shot several trees — which bore fresh, white scars.

The howling stopped, but I didn’t think the beast had gone away. It had been called to heel.

Saul whistled again, drawing out his trill.

I brought up my revolver. I’m a fair left-hand shot, and the pistol was best for close work anyway.

In answer to Saul’s whistle came a low growl.

‘Shuck be hungry,’ Venn said.

‘Chalky,’ I called. ‘It’ll be under the mist. Can you shoot fish?’

The Albino nodded.

‘If it comes into the clearing, blast it!’

I flapped my crushed hand, as if telling Nakszynski — and whoever else might be spying — I was out of the fight. My thought was to leave the sheepdog to the Albino and save my silver for the shepherd.

Saul whistled again, higher — as if trying out signals.

‘Shut up, you damn fool,’ I shouted. ‘Dog knows we’re here. Dog don’t need a foghorn to find us.’

Saul swallowed and was silent. Who’d have thought such a fairy-footed fellow could do so much damage? My hand felt as if it’d been stamped on by an elephant in clogs.

I didn’t like the way this expedition was going.

Either you bring back trophies or scars — often, both. I could claim Old Pharaoh’s horns, but ram wasn’t the game I’d set out for.

Unlike Old Pharaoh, our new caller came stealthily. The mist was all about like a smoking pool, thickening by the moment. I couldn’t see my own boots. The ram’s hump was barely an island. Saul was in it up to his chest. Nakszynski, furthest off, was almost a ghost.

I heard the dog. It might be a Wessex Wolf or a Trantridge Terrier, but it was a dog. Only dogs pant that way. Only dogs rattle spit as they contemplate din-dins.

We were supper on the hoof.

Though it was only early afternoon and less than a mile from Trantridge Hall, we were lost in nighted jungle, with monsters on all sides.

‘Why be you smiling?’ Venn asked.

‘If you don’t know, I can’t tell you,’ I said.

I might die in The Chase. The notion made me hot and angry. It rankled I was so ill-prepared as to find myself in this fix. But a curl of my brain — which everyone from the fulminating Sir Augustus to the calculating Professor Moriarty found fault with — was alive now as at no other time. Some chase women, some chase opium dragons, some chase pots of gold. Dammit, some chase postage stamps or currant buns. I chase these edge-of-life-and-death moments — when an animal or man tries to kill me, and I kill them instead. It’s the surge inside — in the water, behind the eyes, in the loins. That’s what Basher Moran’s about. All the rest is fancy trimming. Nice enough to have, but not real. I’d protested when the Prof diagnosed my ‘addiction to fear’ on our first meeting, but had come to see he’d known me better than I knew myself in those innocent days.

There was that smell again. The Chase smell, vile to the nose and eyes. Old and faint on the reddleman, sharp and new on the dog.

Nakszynski was taken by a red devil which leaped up on his chest and bore him under the mist. I glimpsed eyes of flame and teeth like yellow knives. No point in firing wild. I guess the Albino dropped his guns and tried to get a grip on the neck of the thing with its fangs in his throat.

A long string of terrible Polish words came out of Nakszynski — the only speech I ever heard from him. I’d thought him mute. Then, with a liquid gurgle, his verbal torrent petered out.

‘Saul, run,’ I shouted.

He needed no further orders and bolted for one of his tunnel-paths. I looked for a red streak in the white — and took aim. If Saul Derby played hare to this hound, it might afford me a shot.

Читать дальше

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)