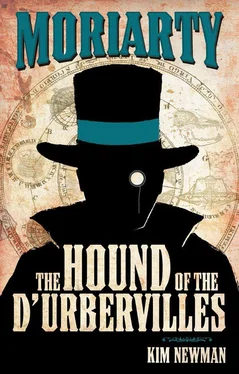

Kim Newman - Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kim Newman - Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the spirit of experiment, I cocked the musket and pulled the trigger.

The blast caught everyone’s attention. I’d like to say a far-off bird tumbled from the sky, but the ball went wild and fell spent. Brown Bess had a fine record in seeing off England’s enemies, but only in the days when Jean François marched close enough for you to smell the garlic breath before you let fire. For accuracy at a distance, you were better off with a longbow.

The crack of the shot echoed.

Stoke froze in mid-kick and Mattie Ball scurried away, quick for someone who’d taken such punishment. She hared across Trantridge Hall’s well-kept lawns towards tangled forest. The Chase. Mattie paused, tiny against the thick, tall trees, and raised a fist. Then she was gone.

No one was inclined to follow.

‘Moran,’ shouted Stoke, ‘what the Devil do you think you’re about?’

‘Put a bounty on the pelt and I’ll bring her down from here,’ I said, raising Brown Bess as if to take aim. The gun, of course, was empty, though I judged Stoke in no state to distinguish a single-shot musket from a repeating rifle. ‘But my understanding is that I’m here to hunt a dog. Anything else is out of season. Now, someone mentioned “hot toddy”. It would behoove us to show the sense to get out of the f--ing rain…’

No one argued the point.

I strode to the door, where I encountered Mod Derby. She gave me a welcoming wink and hand squeeze.

‘Colonel Sebastian Moran, ma’am,’ I said, raising her hand to my lips.

‘Welcome to Trantridge, gallant Colonel,’ she said. Her smile put a dimple in her cheek, and I always appreciate a dimple. ‘You have saved us all from murder.’

It was possible that, after putting her single ball in Stoke, Mattie Ball could have found a bayonet in her shawl, fitted it to the musket and skewered the entire household. I’d have laid odds against, though.

‘I suppose I have,’ I said, as if the thought of receiving thanks never entered my head. ‘All in a day’s work, ma’am.’

‘Modesty,’ she said. ‘But you may call me Mod.’

As with Mattie, I shared a long moment with Mod in which things were settled. Again, my hand took a trick. Without words, something to our mutual benefit was decided.

Stoke, plastered with filth, barged past into his house. He took no notice of what had passed between me and his supposed fancy woman.

We all went into Trantridge Hall.

IX

In conduct under fire, Jasper Stoke had settled the question of the hue of his innards — a sickly custard-yellow. His hands, the servants and the Derby siblings knew it. Even simple Dan’l and fairy-feathered Saul. Having ‘lost face’, as the Celestials say, mine host kept the company waiting for supper. Another theatrical device, no doubt. Probably made sense in German economics.

We convened in a big gloomy room. Blazing logs raised steam from damp furnishings within a few feet of the fireplace. Cow-gum stink suggested wallpaper paste liquefying. Paintings above the mantel, warped by years of radiant heat, did not hang true. However, the warmth did not reach as far as the table. We might have sat in Siberia or Staines for all the good the fire did us.

Gussied up in regimental dinner jacket, displaying a shelf-load of gongs earned by bravery and homicide in the service of the Queen, I did my best to ignore the cold. Mod Derby had abandoned oilskins for more flattering dress, with the neck cut lower than is the London fashion — displaying one or two reasons for favouring counties over capital. She had a head of long, fine, flaxen hair. I was persuaded to recount anecdotes relating to my medals. Seated at my right, Mod jogged my memory by replenishing my goblet with wine from Simon Stoke’s recently discovered cellar. Twittering Saul was to my left, grazing on plates of nuts and berries set out to keep stomachs from rumbling as the evening meal was delayed by the non-appearance of the Master of Trantridge.

Also present were Braham and Nakszynski. Dan’l evidently took his eats with the children or the cowboys. I was surprised to discover another guest at table: that same Parson Tringham who was the unwitting inspiration for Stoke’s dog problem or else an active participant in the plot against him. If the old idiot were puzzled that Stoke — who’d turned him out on his ear the last time he attempted to call — should ask him to dine, it hadn’t stopped him coming. Tringham nattered about long-dead d’Urbervilles as if anyone were interested. He was of our company because Stoke thought he should be grilled for further intelligence. After listening to his witterings, it seemed to me a happier outcome would be if the parson were simply grilled. The Albino had no compunctions about eating a mountie’s liver. Surely, a clergyman’s tongue would at least serve as an appetiser?

I ignored Tringham and maintained attentions to Mod. I had every reason to anticipate private entertainment from that direction.

It nagged, however, that Moriarty had charged me with making detailed observations. Encomia to Modesty Derby’s teats would not interest the cold, sad maniac. No, the Professor would rather have the ramblings of a crackpot genealogist.

Tringham had long sought entry to the archives of the family — meaning the centuried d’Urbervilles, of course, not the jumped-up Stokes. The dinner invitation had persuaded him such was now within his grasp. Well past the age when any self-respecting Eskimo would have packed himself off on an ice floe, his enthusiasms — and his mouth — were unstilled. To be so close to a cherished objective pricked his bump of excitability, and he expostulated about every item in the room.

Of all things, Tringham started on about the paintings.

Over the fireplace was a full-length portrait of Simon Stoke-d’Urberville. In a case of ‘never mind the picture, look at the frame’, an oblong of gilt curly flourishes and oak leaves surrounded the moneylender. The Shylock’s hand rested on a stack of ledgers. The fizzog was bland — the sort you forget while you’re looking at it — but the artist had worked on that long-fingered hand, giving the impression its usual placement was in someone else’s pocket. To Simon’s right, in an equally pretentious, equally twisted frame was a veiled young crone, posed in a bower. Birds perched on her head and arms as if she were a Christmas tree, chickens mixed in with robins and sparrows. This was the widow who’d lingered long abed upstairs before leaving the accumulated boodle to her remittance-man nephew. Being blind, she couldn’t have known how hideous her picture was; being rich, I doubt she was troubled by anyone telling her.

Tringham called our attention to the third in the trinity above the mantel. The matching frame should have been inhabited by murdered Alexander, beloved sprog of Mr and Mrs Stoke-Parvenu. Instead, a red-bearded brute in armour skulked in the woods, a big red mastiff curled about his metal boots. The painting was old, dark and curling at the edges.

‘Pagan Plantagenet d’Urberville,’ the parson said. ‘Circa 1660. Costumed as the original Sir Pagan. Born Percy d’Urberville, he took the names of his ancestors, provable and fancied. He believed secret marriages intermingled the blood of the d’Urbervilles with the line of the rightful kings of England. When the Interregnum ended, Pagan Plantagenet nominated himself as a truer heir to the throne than Charles. Few supported him. Lord Rochester ridiculed him as “Percy the Pretender”. He spent a fortune on forged documents, muddying the waters of d’Urberville scholarship for centuries to come. It’s a frightful bother when a scrap of Norman parchment might be a Restoration fake.’

‘Looks a grim old swine,’ I said. ‘What happened to him?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Professor Moriarty The Hound of the D'Urbervilles» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)