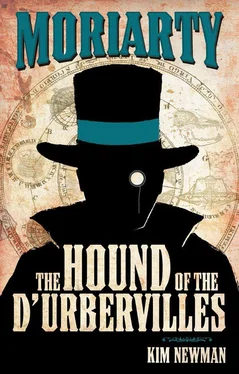

‘Vampyro-whatsit?’

‘Vampyroteuthis infernalis. Hellish vampire squid. Often mistaken for an octopus. Don’t let Singapore Charlie palm you off with anything else. They are difficult to keep alive above their spawning depth. Pressurised brass containers will be necessary. Von Herder can manufacture them, reversing the principle of the Maracot Bell. Use the funds from the Hanway Street jeweller’s, then dip into the reserve. Expense is immaterial. I must have my vampyroteuthis infernalis.’

I pictured what a hellish vampire squid might be. And foresaw unpleasant experiences for Sir Nevil.

‘Now,’ the Professor said, ‘there is just time to catch the last falls. Would you be interested in making haste for Wapping?’

‘Rath-er!’

III

The next few weeks were busy.

Moriarty dropped several criminal projects, and devoted himself entirely to Stent. He summoned minions — familiar fellahs from previous exploits, like Italian Joe from the Old Compton Street Café poisonings, and new faces nervous at being plucked from obscurity by the greatest criminal mind of the age. ‘PC Purbright’, a rozzer kicked off the force for not sharing his bribe-takings, was one such small fish. A misleadingly strapping, ferocious-looking bloke and something of a fairy mary, PCP specialised in dressing up in his old uniform and standing lookout for first-floor men. He had a sideline as a human punching bag, accepting a fee from frustrated criminals (and even respectable folk) who relished the prospect of giving a policeman a taste of his own truncheon. If you paid extra, he’d turn up while you were out with your darby girl and pretend to make an arrest — you could beat him off easily and impress the little lady with your fightin’ spirit. Guaranteed a tumble, I’m told. He came out of the Professor’s study with wide eyes, roped into whatever bad business we were about.

I was sent out to make contact with reliable tradesmen, all more impressed by the colour of Moriarty’s gelt than the peculiarity of his requests. Paul A. Robert, a pioneer of praxinoscopes, was paid to prepare materials in his studio in Brighton. According to his ledgers, he was to provide ‘speculative scientific educational illustrations’ in the form of ‘rapidly serialised photograph cells from nature and contrivance’. Von Herder, the blind German engineer, bought himself a weekend cottage in the Bavarian Alps with his earnings from the pressurised squid tanks and something called a burnished copper parabolic mirror. Singapore Charlie, acting for the mad Chinaman who had cornered the market in importing venomous flora and fauna, was delighted to lay his hands — not literally, of course — on as many squid as we could use.

The pets were delivered promptly, by Chinese laundrymen straining to lift heavy wicker hampers. Under the linens were Herder Bells, which looked like big brass barrels with stout glass view-panels and pressure gauges. A mark on the gauge showed what the correct reading should be, and a foot-pump was supplied to maintain the cosy deep-sea foot-poundage the average h.v.s. needs for comfort. If this process was neglected, they blew up like balloons. Snacks could be slipped to the cephalopods through a funnel affair with graduated locks. The Professor favoured live mice, though they presumably weren’t usually on the vampyroteuthis menu.

Mrs Halifax supplied a trembling housemaid — rather, a practiced harlot who dressed up as a trembling housemaid — to see to the feeding and pumping. Pouting Poll said she’d service the entire crew of a Lascar freighter down to the cabin boy’s monkey rather than look at the ungodly vermin, so hatches were battened over the spheres’ windows at feeding time. Not wanting to follow ma belle Véro to Frozen Knackers, Alaska, Polly did her duty without excessive whining. The Prof spotted the doxy and promised her a promotion to ‘undercover operative’ — which the poor tart hadn’t the wit to be further terrified by.

The squid were quite repulsive enough for me, but Moriarty decided their pale purplish cream hides weren’t to his liking and introduced drops of scarlet dye into their water. This turned them into flaming red horrors. The Professor, cock-a-hoop with the fiends, spent hours peering into their windows, watching them turn inside out or waggle their tentacles like angry floor mops.

Remember I said other crooks hated Moriarty? This was one of the reasons. When he was on a thinking jag, he couldn’t be bothered with anything else. Business as usual went out the window. While the Professor was tending his squid and sucking pastilles, John Clay, the noted gold-lifter (another old Etonian, as it happens), popped round to lay out a tasty earner involving the City and Suburban Bank. He wanted to rope in the Professor’s services as consulting criminal and have him take a look-see at his proposed scam, spot any trapfalls which might lead him into police custody and suggest any improvements that would circumvent said unhappy outcome.

For this, no more than five minutes’ work, the Firm could expect a healthy tithe in gold bullion. The Professor said he was too busy. I had thoughts about that, but kept my mouth shut. I’d no desire to wake up with a palpitating hellish vampire squid on the next pillow. Clay went off in a huff, shouting that he’d pull the blag on his lonesome and we’d not see a farthing. ‘Even without your dashed Professor, I shall get away clean, with thirty thousand! I shall laugh at the law, and crow over Moriarty!’

You know how the City and Suburban crack worked out. Clay is now sewing mailbags, demonstrating the finest needlework in all Her Majesty’s prisons. [23] See: John Watson and Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Red-Headed League’, The Strand Magazine, 1891.

A flash thief, he’d been an asset on several occasions. We’d never have got the Rajah’s Rubies without him. If Moriarty kept this up, we wouldn’t have an organisation left.

One caller the Professor deigned to receive was a shifty-eyed walloper named George Ogilvy. I took him straight off for a back-alley shiv-man, but he turned out to be another bally telescope tosser. First thing he did was whip out a well-worn copy of The Dynamics of an Asteroid (with all its leaves cut) and beg Moriarty for a personal inscription. I think the thing the Professor did with his mouth at that was his stab at a real smile. Trust me, you’d rather a vampyroteuthis infernalis clacked its beak — buccal orifice, properly — at you than see those thin lips part a crack to give a glimpse of teeth.

Moriarty got Ogilvy on the subject of Stent, and the astronomer poured forth a tirade. Seems the Prof wasn’t the only member of the We Hate N.A. Stent Society. I drifted off during the seventh paragraph of bile, but — near as I can recollect — Ogilvy felt passages of On an Inequality of Long Period owed a jot to his own observations, and that credit for same had been perfidiously withheld. It was apparent that, as a breed, mathematician-astronomers were more treacherous, determined and murder-minded than the wounded tigers, Thuggee stranglers, card-sharps and frisky husband-poisoners who formed my usual circle of acquaintance.

Ogilvy happily signed up as the first recruit for the Red Planet League and left, clutching his now-sacred Dynamics.

I ventured a question. ‘I say, Moriarty, what is the Red Planet League?’

His head oscillated, a familiar mannerism when he was pondering something dreadful. He looked out of our window, up into the pinkish-brown evening sky over London.

‘The League is a manufacturer of paper hats,’ he said. ‘Suitable apparel for our cousins from beyond the vast chasm of interplanetary space.’

Читать дальше

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)