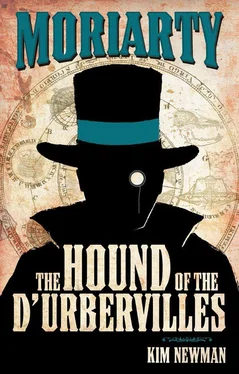

At the conclusion of negotiations, Moriarty was proud owner, through hard-to-trace holding companies, of the Surprise Valley Gold Mine. Amusingly, he was now a major employer in Amber Springs, Utah.

Jim Lassiter/Jonathan Laurence, Jane Withersteen/Helen Laurence and Little Fay Larkin/Rachel Laurence were dead, burned to crackling in the smoking ruins of The Laurels, Streatham Hill Road. It was the gas mains, apparently. And the neighbours had some stories to tell.

What amazed me most was that the Professor had the corpses ready. Chop and I had to wrestle them into beds before the fatal match was struck. I suspected three strangers of the right ages had been ‘burked’, but Moriarty assured Jane the substitutes were ‘natural causes’ paupers rescued from anatomists’ tables. She believed him, and that’s what counts with women like her.

He had a satchel full of documents: passports, birth certificates, twenty-year-old letters, used steamer tickets, bank books, even photographs. If the Lassiter/Laurences wanted to assume other identities, they should have come to him in the first place — when it would have cost less than a gold mine. He let Mr and Mrs Ronald Lembo of Ottowa keep a private fortune of, amusingly enough, £205,000, deposited at Coutts. Not unlimited wealth, but most people should be able to live comfortably on the interest. I’d run through it inside a week.

Jane said the Professor was a wonderful man, but Lassiter knew better. He went along, but knew he’d been bushwhacked. I now think Moriarty even contrived for Drebber to come across the Laurences in the first place. For him, a fugitive in possession of a fabulous gold mine is someone who needs their exile life turned upside down.

Rache was afraid of the man. She wasn’t stupid, just different. She would have to learn a new name, Pixie, and address her parents as Uncle and Aunt, but they’d adopted her in the first place.

Along with the evidence of full lives lived from birth up to this minute, the Lembos found that they had been staying — in a suite at Claridge’s! — in London for several days. Travelling trunks, including entire wardrobes, were ensconced there. I had no doubt the staff would recognise them and they’d be offered their ‘usual’ at breakfast the next day. The family were on a long, leisurely world tour and had tickets and reservations for Paris, Strelsau, Constantinople, and points east. Eventually they would fetch up in Perth, Australia.

In the coach on the way back to Conduit Street, I asked about Drebber and Stangerson.

‘If anyone deserves to be murdered,’ I said, ‘it’s those splitters.’

The Professor smiled. ‘And who will pay us for these murders?’

‘Those two I’d slaughter for free.’

‘Bad business, giving away what we charge for. You won’t find Mrs Halifax bestowing favours “on the house”. No, if we were to take steps against the Danites, we would only expose ourselves to risk. Besides, as you know, giving out an address is often a far more deadly instrument than a gun or a knife.’

I didn’t understand and said so.

‘Elder Drebber mentioned another enemy of the Danites, one Mr Jefferson Hope. Not a fugitive, in this case, but a pursuer. A man with a deadly grudge against our clients which dates back to a business in America which is too utterly tiresome to go into at this late hour.’

‘Drebber was half expecting to run across Hope,’ I said.

‘More like he was expecting Hope to run across him. This is even more likely now. I’ve sent an unsigned telegram to Mr Hope, who is toiling as a cab driver in this city. It mentions a boarding house in Torquay Terrace, Camberwell, where he might find Drebber and Stangerson. I gather they will try to get a train for Liverpool soon, and a passage home, so I impressed on Hope that he should be swiftly about his business.’

Moriarty chuckled.

If you read in the papers about the Lauriston Gardens murder, the Halliday’s Private Hotel poisoning and death ‘in police custody’ of the suspect cabman, you’ll understand. [10] See A Study in Scarlet (John Watson and Arthur Conan Doyle, Beeton’s Christmas Annual, 1887).

When the Professor sets abut tidying up, slates are wiped clean, broken up and buried under a foundation stone.

So, at the end of it all, I was in residence at Conduit Street, part of the family. I was the Number Two in the Firm, the Man in Charge of Murder, but had a sense of how far beneath the Number One that position ranked. I had been near-hanged and shot at, but — most of all — kept out of the grown-ups’ business. Like Rache, good enough to spring the big surprise but otherwise fondly indulged or tolerated, I wasn’t party to serious haggling, just the bloke with the gun and the steady nerve.

Still, I knew how I would even things. I began to keep a journal. All the facts are set down, and eventually the public shall know them.

Then we’ll see whose face is red. No, vermilion.

CHAPTER TWO: A SHAMBLES IN BELGRAVIA

I

To Professor Moriarty, she is always that bitch.

Irene Adler arrived in our Conduit Street rooms shortly after I undertook to assist my fellow tenant in enterprises of which he was the pre-eminent London specialist. In short, sirrah, crime.

The old bread and honey came into it, of course [11] ‘bread and honey’. Yes, the slang expression ‘bread’, usually associated with American crooks or hippies, is Victorian cockney rhyming slang: ‘bread and honey — money’.

. The Professor had me on an honorarium of six thousand pounds per annum. Scarcely enough to make anyone put up with Moriarty, actually, but it serviced my predilection for pursuits the naïve refer to as ‘games of chance’. However, I own that the thrill of do-baddery attracted me, that blood-running whoosh of fright and delight which comes from cocking repeated snooks at every plod, beak and turnkey in the land. When a hunting man has grown bored with bagging tigers, crime can still jangle the nerves and keep up the pecker. The bloodless Moriarty got his jollies in the abstract, plotting felony the way you might play a hand of patience. I’ve heard him say the business of committing the crime itself is but a tiresome necessity, the practical proof of a theorem already solved to his satisfaction.

That morning, the Professor was thinking through two problems. A portion of his brain was calculating the timings of solar eclipses observable in far-flung regions. Superstitious natives can sometimes be persuaded that a white man has power over the sun and needs to be given handy tribal treasures if bwana sahib promises to turn the light on again. Bloody good trick, if you can get away with it [12] Past and future exponents of this long con include the explorer Allan Quartermain (H. Rider Haggard, King Solomon’s Mines, Cassell & Co., 1885) and the journalist Tintin (Hergé, Le Temple du Soleil/Prisoners of the Sun, Casterman, 1949).

. The greater part of his attention, however, was devoted to the breeding of wasps.

‘Your bee is a law-abiding soul,’ he said, in his reedy lecturing voice, ‘as reverent to their queen as the clods of England, dedicated to the production of honey for the betterment of all, buzzing about promiscuously pollinating to please addle-minded poets. They only defend themselves at the cost of their lives, for they sting but once. Volumes are devoted to the care of bees, and apiculture exists to exploit their good nature. Wasps do nothing but sting. Persistently venomous, they fly from one assault to the next. Unwelcome everywhere. Thoroughly nasty sorts. We are not bees, Moran.’

Читать дальше

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)