‘We are not talking about minor mischief,’ said Michael coldly. ‘We are talking about murder and deceit on an enormous scale.’

Ailred glanced across the river, and bent down, as though to brush something from his gown. Then, before Bartholomew or Michael could do anything to stop him, he had pushed off and was scooting down the river at a furious pace.

‘After him, Matt!’ ordered Michael in a shriek. ‘Do not just stand there!’

Bartholomew jumped on to the ice, but feet were no match for skates, and the physician’s awkward slithering was no match for Ailred’s speed and power. The Franciscan rounded a bend on the river, and was gone from sight.

Michael was still furious at Ailred’s escape the following day, claiming he would have had the answers to many questions if the physician had managed to seize the Franciscan before he could skate away. Bartholomew disagreed. He did not think Ailred had been in the mood for throwing light on Michael’s mysteries, and believed the friar would simply have continued to lie. It came down to Godric’s word against his principal’s, and Bartholomew sensed Godric might not keep to his story anyway – he would capitulate, and declare that Ailred had been in after all. Loyalty was important in hostels and Colleges.

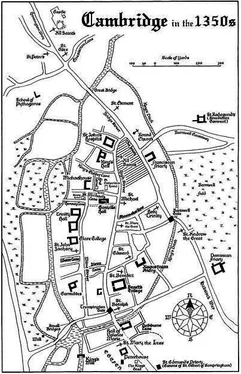

It was almost noon, and Bartholomew had spent the morning trailing around after Michael in a futile attempt to discover where Ailred might have gone. They had visited Ovyng Hostel twice and the Franciscan Friary once, but no one had any idea where a fleeing Grey Friar might go in an emergency. They all said much the same: Ailred was a quiet man, respected and liked by his contemporaries, whose life had revolved completely around his hostel and his students.

‘Only another four days,’ growled Suttone irritably. The bell had just chimed to announce the midday meal, and he was walking across the yard with Bartholomew and Michael, just back from their futile hunt. ‘Then this ridiculous charade will be over.’

‘You mean the season of misrule?’ asked Michael. ‘It has not been too bad this year. The cold weather spoiled some of the wilder schemes, and the fun is wearing too thin now for there to be many more surprises in store for us. Some students are already settling back to their studies.’

‘Quenhyth never stopped his,’ said the Carmelite in disgust. ‘Smug little beggar.’

‘I thought his obsession with learning would endear him to you,’ said Bartholomew, surprised the dour Carmelite so disliked Quenhyth. The student was dull, pedantic and single-minded, which were traits Suttone usually approved in a scholar. ‘He has not engaged in any of the antics surrounding the Lord of Misrule.’

‘Yes and no,’ replied Suttone. ‘His character makes people want to tease him. Indeed, his very presence in Michaelhouse has been the cause of pranks that would not have taken place had he been gone. We must remember to send him away next year – especially if Deynman is reelected.’

They walked into the hall and went to the servants’ screen, where large pots of food were waiting to be distributed. The Fellows were still obliged to serve the others on occasion, and some students continued to occupy the high table, although many had reclaimed their own seats in the body of the hall. The novelty of eating with Deynman had completely worn off for Agatha, however, and she declined his invitations, claiming that she was bored with the prattle of silly boys. She had reverted to dining in the kitchen, along with the rest of the servants.

‘Where is Langelee?’ demanded Michael crossly, snatching up a dish of something that was coloured a brilliant emerald. ‘It will take us ages to serve everyone without him. And what in God’s name is this?’ His attention had been caught by the contents of the bowl.

‘Deynman said all food served today should be green,’ said Bartholomew, laughing when he saw the mouldy bread that Agatha had piled into a basket and the platter of rancid pork that had been prepared. ‘He should have chosen a different colour, because if anyone willingly eats this stuff he deserves to die of poisoning.’

‘That will teach Deynman to make life difficult for Agatha, with his ridiculous demands and orders,’ said Wynewyk in delight. ‘Decaying meat, mouldy bread, cabbage and pea soup with added colouring. It is all green, but Deynman did not specify it also had to be edible!’

‘I shall be glad when this is over,’ said Suttone vehemently, grabbing the bread and preparing to distribute it to hungry students who would be in for a disappointment. ‘Because the servants are not allowed to work, the hall has not been cleaned for days, and it stinks.’

The odour of stale rushes and spilt food was indeed becoming noticeable, and Bartholomew was aware that fewer students used the hall for sleeping, preferring the fresher, if colder, air of their own rooms. The walls were splattered with wine and fat, where the Fellows’ inexpert handling of heavy serving vessels had resulted in mishaps, and the floor was lumpy with discarded scraps. It had almost reached the point where Bartholomew felt obliged to scrape his feet clean before he left.

He escaped from the hall as soon as Deynman said the final grace. It was an unusually short meal, because so little was actually edible, and it was not long before the students were clamouring to leave, so they could find victuals elsewhere. Because his room was still encased in a cocoon of snow – although it was melting quickly and it would not be long before it would be accessible again – Bartholomew went to William’s chamber.

The friar had not been obliged to consume green food. He sat replete and contented, with the remains of fish-giblet stew, and fine wheat-bread, which Bartholomew imagined had also been enjoyed by Agatha, lay in front of him. William informed Bartholomew that his meal had been excellent and that he was considering ‘breaking’ his other leg in order to be cosseted and excused from unpleasant duties.

‘Do not let Agatha know you are only pretending to be infirm,’ the physician advised. ‘If she discovers her charity has been in vain your life will not be worth living.’

‘The weather is changing,’ said William ruefully. ‘And the ground underfoot is not nearly as slick as it was. You can remove the splint in a day or two, but I may bribe you with books again, if I feel the need for a period of respite.’

‘Bribe away,’ said Bartholomew, running his hand lovingly over the fine cover of his Bradwardine. ‘Did you know that Michael spent all morning searching for one of your brethren? Ailred from Ovyng ran away when our questions became too uncomfortable.’

‘I heard,’ said William. ‘And I am astonished. Ailred is a kindly, God-fearing man. I cannot imagine him fleeing from anything.’

‘Has he ever spoken to you about kin from the village of Fiscurtune, near Lincoln? No one else seems to know much about his family.’

‘He has kin,’ replied William. ‘Or should I say had kin, since we Franciscans often renounce family ties once we have taken our vows. I know a little about Ailred’s, though, because we went on retreat to Chesterton together once. He talked about them then.’

‘What did he say?’ asked Bartholomew, feeling his excitement quicken.

‘Very little,’ came the disappointing reply. ‘He has a brother. Or was it a sister? I cannot recall now. And there is a nephew he is fond of.’

‘Do you know anything else about them?’ asked Bartholomew.

William thought for a moment. ‘They used to go fishing together.’

Bartholomew told Michael about his conversation with William as they sat in the Brazen George, eating roasted sheep with a sauce of beetroot and onions. There were parsnips and cabbage stems, too, baked slowly in butter in the bottom of the bread oven, so that the flavour of yeast could be tasted in them. The more he thought about it, the more likely it seemed to Bartholomew that Ailred was indeed associated with the dead John Fiscurtune. And he wondered whether there was some significance in the fact that Walter Turke had died while skating, when Ailred had shown himself to be a veteran on ice.

Читать дальше