‘Other than the name of his home manor?’ asked Godric. ‘He always catches more trout from the river than anyone else, and he prefers fish to meat. But that is all.’

‘It may be enough,’ said Michael, nudging Bartholomew in the ribs. ‘But we should have this discussion with Ailred himself. Come, Matt. Let us see this Franciscan on his skates.’

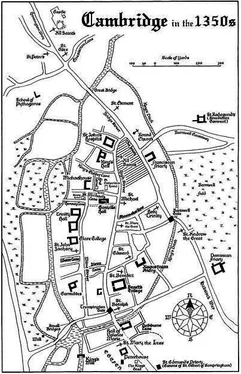

Bartholomew and Michael took their leave of Godric, and struggled back through the melting drifts in the direction of the Great Bridge. At last they reached the river, which curved around the western side of the town and looked like another road, with its frozen surface and recent dusting of snow. However, all manner of filth lay strewn across its surface – sewage, animal manure, inedible items from the butchers’ stalls, fish entrails, rotting vegetables, and some items Bartholomew dared not identify, although he suspected they had once belonged to a dog.

Because it was a winter Sunday, and a day when many folk enjoyed a day of rest, there was a large gathering of people near the Great Bridge and on the water meadows that lay to either side of it. The fields were prone to flooding in spring, and so were mostly devoid of houses – although a few desperate folk had erected shacks along the edges. The meadows were used for grazing cattle in the summer, but now they were blanketed in snow and were the venue for the town’s traditional First Day of the Year games.

Sheriff Morice had seized control of the event, and was sitting astride his handsome grey stallion, watching the proceedings from the vantage point of the bridge itself. He was surrounded by his lieutenants, a gaudy and frivolous group who, like Morice, were more interested in making money than in promoting law and order. The townsfolk seemed to be enjoying the games, although there was none of the excited anticipation associated with the annual campball.

A number of activities were in progress. Butts had been set up, and townsmen were showing off their skills with bows and arrows. Dangerously close to their line of fire was a game of ice bandy-ball, where strong men smacked a small wooden sphere with terrific force, so that anyone in its path could expect serious injury. Meanwhile, an impromptu session of ice-camping had started, using the same leather bag that Agatha had powered into the gargoyle’s maw a few days earlier. It was more a case of ‘snow-camping’ than ice-camping, because the soft surface was slowing the speed of the game. Bartholomew thought this would mean fewer injuries for the participants, although he could not but help notice that it, too, ranged perilously close to the butts.

Nearby St Giles’s was supplying church ale to the spectators, and women stood behind trestle tables, selling slices of the sausage-like hackin. A shrid pie was on display, too, decorated with its traditional pastry baby-in-a-basket. Bartholomew noticed that the women had cut their wedges carefully around the crib, with the result that the baby was left teetering atop a pastry precipice.

A crowd had gathered around a stall where hot spiced wine was being sold for wassailing. Some folk had already toasted the health of too many friends, and had passed out in the snow. Bartholomew hoped they would not be left to freeze to death after the games had finished, but was reassured by the watchful presence of the Austin Canons from the nearby Hospital of St John. He felt a tug on his cloak, and turned to see Sergeant Orwelle, a grizzled veteran who usually manned the town’s gates.

‘Morice is demanding a penny from anyone who wants to play in the games,’ he said with disapproval. ‘That is why there are not as many folk as we expected. Morice says it is because I closed the river, but I think it is because he is charging for something that was free last year.’

‘You closed the river?’ asked Bartholomew. ‘Because of the thaw?’

Orwelle nodded. ‘I have lived near the water for fifty years, and I know its wiles. The ice stopped being safe this morning, so I gave orders that no games should be played on it today. Morice was furious, because he wanted to hire out skates for ice bandy-ball and ice-camping. He claims my actions have lost him a fortune.’

‘He is not fit to be Sheriff,’ said Michael in disgust, looking angrily at the arrogant man on the grey horse.

‘Why are you here, Brother?’ asked Orwelle. ‘Have you come to try your hand at bittle-battle? I can lend you my club and a ball, so you will not have to pay to hire Morice’s.’

‘Not in the snow, thank you,’ said Michael haughtily. ‘It would ruin my stroke. I am good at bittle-battle; no one can use a long stick to knock a tiny ball into distant holes like me.’

‘How about wrestling?’ asked Orwelle, looking Michael up and down. ‘You are probably good at that, too.’

‘Tilting,’ said Michael, picking the game where the object was to charge a horse at a pivoting bar and knock it hard before it swung back and dismounted the rider. ‘I excel at tilting. But I am not here to win prizes today. Have you seen Ailred from Ovyng? We shall never find him among these crowds.’

‘He left when I closed the river, because he wanted to skate. His students are here, though – in that snowball fight over there.’

Bartholomew looked to where he pointed, and could see Franciscan habits among the swirling crowd heaving icy missiles at anyone in the vicinity. Shrieks and howls filled the air, not all of them delighted ones. The physician could see blood on several faces, and suspected the Sheriff would need to police the event very carefully if he did not want it to turn into something darker and more dangerous. Already apprentices, fresh from the wassail stall, were reeling to join the throng, while scholars were massing on the sidelines, evidently planning some kind of retaliatory strategy.

‘Where did Ailred go?’ asked Michael. ‘Home?’

‘To find some quiet patch of river where he can skate without being warned of the dangers, I imagine,’ said Orwelle disapprovingly. ‘Although, I must say he is extremely good; I have watched him before.’

Bartholomew and Michael abandoned the simmering atmosphere of the Sheriff’s winter games, with Michael passing orders to Beadle Meadowman to keep an eye on the snowball fight and Bartholomew promising the Austin Canons his services, should they be required later. They then made their way along the towpath that ran beside the river.

The river possessed several arms and drains that ran this way and that, comprising an interlacing system of waterways. The King’s Ditch and the river met in the south near Small Bridges, where they formed the Mill Pool. The King’s Mill, which stood nearby, used the power of the swift current to drive its sails and grind its corn, although this could not operate as long as the river was frozen. It stood still and silent, the massive wheel that drove the mill lifted out of the water to protect it from the ice. The Mill Pool itself was sluggish compared to the rest of the river, so it invariably froze first and thawed last in icy weather. It was here that Bartholomew and Michael found Ailred.

The Franciscan had attracted a small but appreciative audience as he demonstrated his skills. His bone skates were fastened to his feet with leather thongs, and the blades had been carefully sharpened, so they hissed and sizzled as they cut across the ice. Others had also been enjoying a little gentle recreation while the ice remained firm, but had ceased their efforts to watch the spectacle provided by the priest. Ailred seemed to soar, rather than skate. He jumped and skipped and danced and turned, and did not seem like the same man who had sat grim-faced gutting fish in Ovyng’s dismal chamber a few days before.

‘Lord!’ muttered Michael, impressed. ‘Where did he learn to do that?’

Читать дальше