‘Do you think Thorpe and Edward killed Bosel?’ asked Michael of Bartholomew, ignoring the Sheriff’s ire that he should be blamed for something his predecessor had done.

Tulyet raised his eyebrows and spoke before the physician could reply. ‘I have just told you they were both in a meeting last night. How can they be responsible?’

‘Because you do not need to be present when your victim dies of poison,’ Michael pointed out. ‘They could have given Bosel the doctored wine hours before they went to this meeting.’

Tulyet considered, then nodded towards the madwoman. ‘In my experience the person who finds a murdered corpse is often its killer, and she seems to have no rational reason for being with Bosel. Do I know her? She looks familiar.’

‘Where would she find the money to buy wine and poison?’ asked Michael. ‘And why kill Bosel when she is a stranger in Cambridge, with no reason to harm any of its inhabitants?’

‘How do you know she had no reason to harm Bosel?’ asked Bartholomew reasonably. ‘We know nothing about her, not even her name. And she is out of her wits, so is not rational. She may have killed him because she thought he was someone else.’

‘Shall I arrest her, then?’ asked Tulyet. ‘I will, if you think she is guilty.’

‘I do not know,’ said Bartholomew, unwilling to condemn anyone to the Castle prison. It was a foul place, full of rats and dripping slime. ‘She might be telling the truth – that she found the body and did not like to leave it alone until a priest came.’

‘Perhaps she stole the wine,’ suggested Tulyet, reluctant to dismiss a potential culprit too readily. ‘Or Bosel did – and got more than he bargained for. Unfortunately, I am too busy to look into this myself. Repairs to the Great Bridge begin today, and I must be there to supervise.’

‘Why?’ asked Michael curiously. ‘That is the burgesses’ responsibility, not yours.’

Tulyet’s face was angry. ‘Because the burgesses, in an attempt to cut costs, want to use the cheapest labour available: the prisoners in my Castle. That is why we had that meeting last night. I objected very strongly, but I was outvoted on all sides, so debtors, thieves and violent robbers will be set free to work on the bridge this very afternoon. I need to make sure they do not try to escape – or that my soldiers will know how to stop them, if they do.’

‘ When they do,’ muttered Bartholomew.

‘It is about time the bridge was mended,’ said Michael. ‘It almost collapsed when I last used it.’

‘It has been subjected to some very heavy loads recently,’ agreed Tulyet. ‘But, besides watching forty able-bodied villains, I am also obliged to keep a close watch on Thorpe and Edward. I am sure they came here intending mischief. I shall have to delegate Bosel’s murder investigation to Sergeant Orwelle.’

‘Orwelle is a good man,’ said Bartholomew, although he thought it a pity that Bosel was to be deprived of the superior talents of the Sheriff. ‘He will do his best to solve this crime.’

‘And he has a limited number of suspects,’ added Michael. ‘Thomas Mortimer and his clan are the only ones with a known motive.’

‘Well, there is her,’ said Tulyet, pointing at the woman. ‘However, I have a feeling you are right: Bosel’s death probably does have something to do with the Mortimers. Bosel’s evidence was not worth much, but without it I have nothing.’

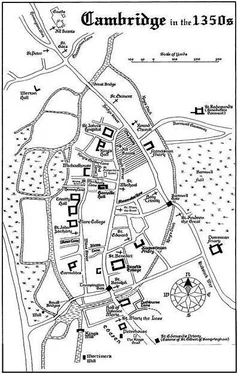

Bartholomew and Michael left the Sheriff, and resumed their walk to Isnard’s house with Quenhyth and Redmeadow trailing behind them; Deynman had been charged with taking the woman to St John’s Hospital. They passed through the Trumpington Gate, then cut down the narrow lane opposite the Hall of Valence Marie, which was rutted with water-filled potholes deep enough to drown a sheep. Isnard’s home was on the river bank, overlooking the Mill Pool.

The bargeman’s residence was not in a good location. It was near both the Cam and the King’s Ditch, both of which were stinking open sewers that contained all manner of filth. Being by the Mill Pool did not help either, since the current slowed there, causing the foulness to linger rather than being carried away. The pool was fringed with reeds and, in the spring and summer, Bartholomew imagined the bargeman would be plagued with swarms of insects. The house was near the town’s two largest watermills, too, and, although Bartholomew supposed their neighbours would grow used to the rhythmic clank and rumble of their mighty wheels, he did not think he would ever do so. As he picked his way along the muddy path to Isnard’s home, he studied them.

The King’s Mill was a hall-house located a few paces upstream from the Mill Pool. It spanned an arm of water that had been artificially narrowed to make it run faster and stronger. Its vertical wheel was of the undershot style, designed so that water struck its lower blades to set it in motion. The power generated was transferred to the mill itself by means of an ‘axle tree’ – a shaft connected to a series of cogs and wheels. It was not just the swishing, clunking sound of the wheel as it turned that was so noisy, but the rattle of the machinery, too.

Standing a short distance from the King’s Mill was Mortimer’s Mill, owned and run by the man who had injured Isnard. It was smaller than its competitor but just as noisy, and a good deal more filthy. The King’s Mill ground grain for flour, but Mortimer’s Mill had recently been converted for fulling cloth, a process that entailed the use of a lot of very smelly substances, all of which ended up in the river. The bargeman would be able to see Mortimer’s enterprise from his sickbed, and Bartholomew wondered what he thought as he lay maimed and fevered, while the author of his troubles continued with the work that was making him a very wealthy man.

As Bartholomew listened to the repetitive rattle coming from the King’s Mill, he became aware that it was slowing down. There was not as much water in each of the wheel’s scoops, and the busy sound of its workings faltered, as though it had run out of energy. By contrast, Mortimer’s Mill was operating at a cracking pace, and, if anything, was going even faster. He saw people hurry from the King’s Mill and start to inspect their wheel, as if they could not understand why it had lost power. He watched their puzzled musings for a moment, then turned to enter his patient’s home.

The house was poor and mean. Its thatched roof was in need of repair, and plaster was peeling from its walls, exposing the wattle and daub underneath. A chamber on the ground floor held a table, a bench, a hearth and a shelf for pots; an attic, reached by a ladder, was where Isnard usually slept. Since the bargeman’s injury meant he could not climb the steps, Bartholomew had carried his bedding downstairs the previous day.

The physician was fully expecting him to develop a fever that might kill him, and was surprised, but pleased, to discover that the burly bargeman had not succumbed. He was even more surprised to find him sitting up and talking to a visitor – a man named Nicholas Bottisham, who was Gonville Hall’s Master of Civil and Canon Law. Bottisham was regarded as one of the finest scholars in the University, possessing a mind that retained facts and references and made him a superb disputant. He had recently taken major orders with the Carmelites, and his new habit was still pristine. His complexion was florid and uneven, as a result of a disfiguring pox contracted in childhood, and his hair was cut high above his ears in a way indicating that Barber Lenne had been at it. He stood when Bartholomew, Michael and the two students entered.

‘You are a popular man, Isnard,’ said Bottisham, picking up his cloak from the table. ‘I shall leave you, before you have so many guests that your walls burst and your house tumbles about your ears.’

Читать дальше