Michael chattered next to him, trying to establish links between recent events. He said he understood why Clippesby might have attacked Rougham, but saw no reason for him to have killed Chesterfelde and the man in the cistern. He determined that when he next visited Clippesby, he would ask whether the Dominican knew Eudo and Boltone; he was sure they were involved in the mystery, but uncertain as to how.

‘And we cannot forget Abergavenny and his associates,’ he added. ‘If Gonerby did indeed die from a bite, then there is a connection there, too.’

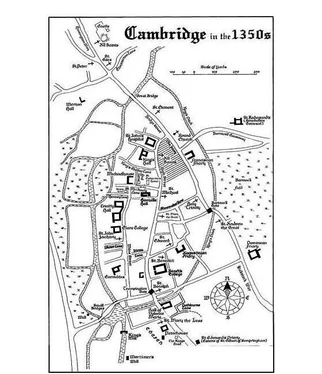

Bartholomew was too tired to fit the facts into a logical pattern, and almost at the point where he did not care. He crossed the deserted Great Bridge and began to stride up Castle Hill, Michael wheezing at his side. It was a steep incline for Cambridge, topped by the brooding mass of the Norman fortress. This was a formidable structure, with a stone tower standing atop a sizeable motte, and sturdy curtain walls that defended its bailey. All Saints stood near its main gate. The church had once been impressive, and had served as castle chapel before a purpose-built one had been raised inside. Then All Saints had been relegated to parish church for those who lived in the nearby hovels. Poverty and dismal living conditions had conspired against these people when the plague had struck, and most had died. With no congregation and no priest, the building had crumbled from neglect. Now, when people referred to All Saints, most folk thought of the grander All-Saints-in-the-Jewry.

In the dark, it looked even more unprepossessing than it did during the day. The roof timbers were cracked and broken, giving its top a jagged, uneven look. Ivy climbed up its walls and seemed the only thing keeping them standing, and the squat tower with its broken battlements was a sinister and forbidding crag against the night sky. Bartholomew inched along the weed-encrusted path that led to the west door, moving slowly so his feet did not catch in the matted undergrowth. Michael followed, swearing when he stumbled and stung himself on nettles.

The physician pushed open a door that hung from broken hinges, and wondered what the Oxford men thought of being provided with an abandoned chapel in which to lay their dead. It was disrespectful, and it occurred to him that one might be so affronted on Chesterfelde’s behalf that he might attempt to avenge the insult. Duraunt would not, Bartholomew thought: he would believe prayers would do Chesterfelde more good than fine surroundings, while Polmorva would do nothing that did not benefit him directly. And the others? Bartholomew did not know them well enough to say. He took a deep breath as he stepped through the door and into the black interior.

Water dripped in echoing plops, and the entire place stank of mould and rotting wood. The ivy that coated the outer walls had made incursions inward, too, crawling through windows and those parts of the roof that were open to the elements. People had been in to see what they could salvage, and most of the floor had been prised up and spirited away. Paint peeled from the walls, although, when Michael lit a lamp, Bartholomew could still make out some of the images that had been lovingly executed by some long-dead artist. St Paul was recognisable amid a host of faceless cherubs, while the Virgin Mary gazed from the mural over the rood screen.

Bartholomew took the lamp and made his way to the chancel, where he supposed the body of Chesterfelde had been taken. Even in a derelict church, this was the most sacred part, and it had not suffered as badly from looters as had the nave. It still possessed some of its flagstones, and it was on these that the water dripped, sending mournful echoes along the aisles. The altar had been left, too. It was oddly clean, and Bartholomew recalled events from several years before, when he had witnessed acts of witchcraft around it. He supposed the place was still used for devilish purposes, because it was apparent that someone visited regularly – the chancel was relatively free of the debris that littered the nave and there was evidence that candles had been lit. But then, perhaps someone loved All Saints, and performed small acts of devotion to ensure it retained some of its dignity.

Chesterfelde lay on what looked to be a door resting atop a pair of trestles. He was covered by a grey woollen blanket, and a piece of sacking moulded into a cushion near his feet suggested someone had been kneeling there. Since Duraunt was the only priest in the party from Oxford, Bartholomew supposed the crude hassock was to protect his ancient knees.

The body was much as Bartholomew remembered from his examination three days before, although someone had wiped its face and brushed its hair. He had assessed it meticulously the first time, and knew he would learn nothing new by repeating the process. All he wanted to do that morning was study the wrist and see whether he could identify teeth marks.

He peeled back the cover and pushed up Chesterfelde’s sleeves. The body’s right arm was unmarked, although there were patches of hardened skin around the thumb that were familiar to a physician used to treating scholars. They were writing calluses, caused by the constant chafing of a pen. Then Bartholomew inspected the left wrist. The wound was still there, ragged and open, but it was now washed free of blood.

‘If Chesterfelde died near the cistern – and the stains there suggest he did – then someone cleaned him up before taking him to the hall,’ he said. ‘The only reason for anyone to do such a thing is to mislead those examining the body. I cannot begin to imagine why: it does not matter whether Chesterfelde died from a slash to his arm or a stab in his back. It is murder, regardless.’

‘Are you certain the wrist wound killed him? Is it possible he injured himself, but managed to stem the bleeding, and died from some other means? Poison, maybe? Or suffocation?’

‘It is possible, but this wound unattended would certainly have brought about his death. Look. You can see the severed blood vessels.’

Michael made a disgusted sound at the back of his throat. ‘A simple yes or no would have sufficed, Matt. But what made the injury? Can you tell whether it was teeth?’

‘It is ragged,’ said Bartholomew, inspecting the gash carefully. ‘And longer than it is deep.’

‘Meaning?’ asked Michael impatiently, uninterested in the mechanics of the damage and wanting only to know what it implied for his investigation.

‘Meaning it is a slashing wound, not a stabbing one.’

Michael considered. ‘Well, you do not stab with your teeth – unless you have long fangs like Warden Powys of King’s Hall. You are more likely to slash with them.’

‘But not in this case, Brother,’ said Bartholomew, straightening up. ‘I see no evidence that teeth were used, just some blunt old knife that was in sad need of sharpening.’

‘Clippesby did not do it, then?’ asked Michael, relieved. ‘So, we are back to our original suspects – Eudo and Boltone, and the Oxford men: Polmorva, Spryngheuse, Duraunt and the merchants.’

‘Not Duraunt,’ pressed Bartholomew doggedly. ‘But do not leave Dodenho of King’s Hall off your list. He knew Chesterfelde, and he lied about it. And there is that curious business about his silver astrolabe, which was stolen, then found, then appeared at Merton Hall in the tanner’s hands.’

‘I have not forgotten Dodenho,’ said Michael. ‘Nor his conveniently missing colleagues, Hamecotes and Wolf. Nor Norton, either, who also admits to knowing Oxford.’

‘It is a pity Okehamptone is buried,’ said Bartholomew, replacing the sheet over Chesterfelde, and glad that particular task was over. He recalled what Clippesby had said about the scribe’s death: that the geese knew more about it than Michael. Was the man spouting nonsense in his deranged state, or was he playing some complex game in which only he knew the rules? ‘I would be happier if we knew for certain Clippesby had nothing to do with that, either.’

Читать дальше