‘Ruthless, devious and greedy,’ supplied Alice, when the Abbot faltered, searching for a tactful phrase. ‘The kind of man who should only be addressed in the presence of reliable witnesses, lest he later twists your words or forges your signatures.’

Multone winced, although he made no effort to contradict her. ‘I expect him at any moment.’

‘Then perhaps we could discuss my business before he arrives, Father Abbot,’ suggested Chozaico uneasily. ‘Because … well, you understand.’

‘Indeed,’ nodded Multone quickly. ‘The founding of an obit for Stiendby is none of his affair.’

‘Stiendby is dead?’ asked Langelee, shocked. ‘He was another of Zouche’s executors. Why did no one inform me?’

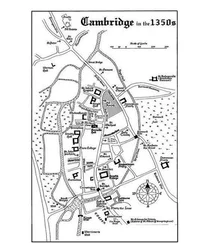

‘Because hiring messengers to ride all the way to Cambridge is expensive,’ replied Anketil. ‘Besides, Sir William wrote when Myton died, and you never replied. Naturally, we all assumed you were engrossed in your new life, and the old one no longer held any interest for you.’

Langelee glared at him. ‘I was so stricken with sorrow that responding must have slipped my mind. But never mind this – what happened to Stiendby?’

‘He died last year, of spotted liver.’ Abbot Multone shuddered. ‘God deliver us all from such a vile affliction! It took Neville, too – another executor – although that was five years ago now.’

‘What is spotted liver?’ asked Bartholomew curiously, while Langelee’s jaw dropped with the realisation that events in York had moved on without him during the time he had been absent.

‘A terrible disease,’ replied Multone bleakly. ‘Best not ask.’

The Abbot turned his attention to the document Chozaico produced and began to scan through it, although he shoved it rather furtively up his sleeve when Oustwyk appeared with yet another guest. There was immediate disquiet among those already there, and it was obvious that none of them appreciated being thrust into the company of the latest arrival.

Dalfeld was a tall man with a mop of black curly hair and restless eyes. There was nothing to identify him as a member of the Franciscan Order, because he wore a green belted tunic called a gipon, and fine calfskin boots. However, although both were of excellent quality, they were sadly stained with mud and one sleeve had been ripped. He was also wet, and wore no hat or cloak.

‘I have just been robbed,’ he raged, stamping into the room and making directly for the fire. He jostled Alice as he went, and only a timely lunge by Chozaico prevented her from falling. ‘Me, a poor friar!’

‘Robbed?’ asked Abbot Multone in astonishment. ‘By whom?’

‘If I knew that, the villain would be kicking on a gibbet by now,’ fumed Dalfeld viciously. ‘He knocked me into the filth of the street, and then stole my purse, my new hat and my favourite cloak. And although there were a dozen witnesses, not one admitted to seeing anything.’

‘Fleeced of your belongings,’ said Alice flatly. ‘Now you know how your victims feel.’

‘I do not fleece people,’ snapped Dalfeld. ‘I merely apply the law.’

‘It invariably amounts to the same thing with you,’ said Chozaico quietly. ‘And a little conscience would not go amiss. What you do is rarely just, and your religious vows–’

‘How dare you lecture me!’ snarled Dalfeld. ‘You are a damned French spy.’

‘I hardly think–’ began Multone, shocked, while the colour drained from Chozaico’s face.

‘I know why you asked me here,’ interrupted Dalfeld curtly. ‘But the answer is no: I wrote no document giving Huntington to Michaelhouse. Ergo , the vicars will win this case. But that was a foregone conclusion when they went out and hired the best lawyer available to represent them: me.’

‘You are not the only notary-public in York,’ said Langelee stiffly. ‘Zouche may have asked someone else to produce the codicil.’

‘He may,’ acknowledged Dalfeld. ‘But if you do discover one, you will have to prove it is not a forgery – especially as I imagine Oustwyk has already offered to introduce you to men skilled at producing fraudulent writs. However, I am not easily deceived, so you may as well save your money and go home now. You stand as much chance of besting me as you do of flying to Venus.’

Before the scholars could react to Dalfeld’s remarks, Oustwyk appeared with yet another visitor. Exasperated, the Abbot hauled his steward into a corner, whispering fierce admonitions, but although Oustwyk nodded understanding, he did not seem contrite.

The newcomer’s eyebrows shot up in surprise at the number of people the Abbot was entertaining, but he squeezed himself into the solar gamely. He aimed for Langelee, and gripped the Master’s arm in comradely affection. His sword and short cloak said he was a knight, and he carried himself with confidence and dignity. He was in his fifties, with iron-grey hair and a weather-beaten face that might have been austere, were it not for his ready smile.

‘Scholarship suits you, Langelee,’ he said warmly. ‘You look younger than you ever did here.’

‘This is Sir William Longton,’ said Langelee to his colleagues. He grinned at the knight. ‘It is hard to believe that twelve years have passed since Zouche took us to put an end to the Scots’ unrest at Neville’s Cross. It feels like yesterday.’

Sir William sighed. ‘It does. Thoresby is an excellent archbishop, who has given up all his royal appointments to concentrate on running his diocese, but I liked Zouche.’

‘I liked him, too,’ said Alice. ‘He did not appreciate music, but he was a fine figure of a man.’

‘He did nothing untoward, Mother,’ said Isabella, aware of the conclusions that Bartholomew, Michael and Radeford were drawing from this particular remark. ‘He was not that sort of person.’

‘No,’ agreed Langelee. ‘He was decent and practical – not irritatingly devout, like many clerics, but a man for the people. I shall visit his chantry chapel later, and pray for his soul.’

‘I only wish you could,’ said Sir William sadly. ‘But unfortunately, it is not finished.’

Langelee frowned. ‘Not finished? But that is impossible! It was started long before he died, and by the time I left, it was half done. He left ample money–’

‘It ran out,’ interposed Dalfeld, all smug malice. ‘He should have provided more.’

‘Ran out?’ exploded Langelee. ‘But he left a fortune – enough to pay for a shrine twice over. He told me so himself.’

‘As he told you he left Huntington to Michaelhouse?’ asked Dalfeld snidely.

Langelee rounded on Anketil. ‘You are his executor – appointed to see his last wishes carried out. Why is his chapel not ready after nearly six years?’

Anketil raised his hands placatingly. ‘Masons are costly, and so is stone. We all thought what he left would be more than sufficient, but we were wrong.’

‘Then why does the minster not pay?’ demanded Langelee.

‘Because it is about to begin remodelling the choir, and there are no funds to spare,’ explained Multone. He brightened. ‘Have you seen the plans? They are pleasingly ambitious, and–’

‘He was good to you, Anketil,’ shouted Langelee angrily. ‘He defended Holy Trinity against those spying accusations, and he helped you secure lucrative benefactions.’ He whirled around to include Dalfeld in his tirade. ‘And he was generous to you, too. He introduced you to wealthy clients and he left you property. Is this how you repay him? By failing to complete his chantry?’

‘It is not my concern,’ stated Dalfeld indignantly. ‘ I was not one of his executors.’

‘But you were his lawyer!’ yelled Langelee, unappeased. ‘He trusted you – both of you.’

Читать дальше