He reached the minster, and took refuge behind one of its sturdy buttresses. Peering around it, he was just in time to see the top of the tower wobble, and then glide out of sight in a cloud of dust with a sound like distant thunder.

It was not many moments before people began to pour out of the minster, to see what was responsible for such an unearthly medley of groans, rumbles and crashes. They pointed and yelled, surging forward to stand unwisely close to the dust-shrouded ruins. The vicars-choral were hot on their heels, pleading with them to watch from a safer distance. Few heeded the advice.

Bartholomew joined the stream of spectators, shoving through them frantically as he hunted for Michael and Cynric. They were nowhere to be found, and despair began to seize him.

‘There you are,’ came an aggrieved voice, and he whipped around to see Michael, dirty, bruised and dishevelled, but certainly alive. Cynric was beaming at his side. ‘Where have you been? We were worried.’

‘Thank God!’ Relief turned Bartholomew’s legs to jelly, and he grabbed Michael’s shoulder for support. ‘I thought you were still inside – that Cynric was unequal to carrying you.’

Michael’s eyes narrowed. ‘I sincerely hope you are not suggesting that I am fat.’

‘Or that I am feeble,’ added Cynric, although the gleam in his eyes said he was amused.

Bartholomew had no wish to linger by the rubble, so he led the way to the minster, hoping one of the vicars would give him something to drink, to wash the grit from his mouth and throat. Inside, he was startled to hear people cheering, and was obliged to shout when he asked Talerand what was happening.

‘The tidal surge,’ the Dean hollered back. ‘It was smaller than predicted, and the devastation is not nearly as great as we feared. The water levels are already falling. And look!’

They followed the direction of his pointing finger and saw bright light arch through the stained glass of the chancel windows. It had stopped raining, and the first sunshine in days told those inside that although there would be a lot of work to do before York recovered, the worst was over.

The Dean bustled away, all smiles and eccentric bonhomie, and Bartholomew leaned against a wall, feeling tainted by the entire encounter with Helen, Isabella, Marmaduke and their deranged plans. He was so engrossed in maudlin thoughts that he did not see Langelee until the Master was standing right in front of him. Langelee regarded his Fellows’ torn and dirty clothes with rank disapproval.

‘I hope you have not made a mess in the library,’ he said. ‘That is where you have been, is it not? Securing the documents that will convict Chozaico and his accomplices? As I ordered?’

‘Not exactly,’ replied Michael tiredly. ‘But what are you doing here? I thought you were helping Alice to settle refugees in Holy Trinity.’

Langelee waved an airy hand. ‘She is an extremely efficient woman, and needed no assistance from me. So I decided to risk the bridge, and spend my time doing a little business for Michaelhouse. I have been negotiating with the vicars about Huntington.’

‘We have some bad news about that,’ said Michael. ‘We met Jorden earlier, and he told us that a codicil was never made. Ergo , we have no right to the place, no matter what Zouche intended.’

‘Yes, I met Jorden, too,’ said Langelee slyly. ‘It was what prompted me to race here before all was lost. Ah, Dalfeld! There you are. Have you finished?’

‘Marmaduke sent for you,’ said Michael, as the oily lawyer approached. ‘Why did you not answer his summons?’

Dalfeld winked. ‘Because your Master has precipitated a situation that promises to be rather lucrative. I shall see what Marmaduke wants later.’

‘Well?’ demanded Langelee impatiently. ‘Did the vicars agree to my terms?’

‘Yes,’ replied Dalfeld. ‘They are desperate to make amends and have agreed unanimously to what you have proposed, giving me full authority to negotiate the finer details.’

‘Make amends for what?’ asked Bartholomew suspiciously.

‘Isabella wrote a powerful letter to Jafford,’ explained Langelee. ‘In which she argues that the flood is God’s anger at the vicars’ treatment of Michaelhouse. It certainly convinced me, and it convinced him, too. He and the bulk of his colleagues are eager for a reconciliation, so I suggested a solution that suits us all.’

‘What solution?’ asked Bartholomew uneasily. ‘What have you done?’

Langelee turned back to Dalfeld. ‘Is that the document which will make our agreement legal and binding?’

‘Yes,’ replied Dalfeld. ‘It states that Michaelhouse will relinquish all claims on Huntington in exchange for eighty marks, payable immediately. I think you will agree that it is a generous sum.’

Bartholomew gaped as Dalfeld handed Langelee a heavy purse. ‘No!’ he exclaimed, shocked. ‘It is not right!’

‘A hundred marks, then,’ sighed Dalfeld, beginning to count out more coins. ‘But that will be their final offer.’

‘Very well,’ said Langelee blandly. ‘Where do I sign?’

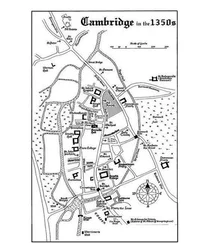

Cambridge, May 1358

It did not take long for Bartholomew, Michael, Langelee and Cynric to settle back into College life. The Summer Term was always busy, with students preparing for final disputations, and they threw themselves into the familiar routine with a sense of relief. Their colleagues had been delighted with the arrangement Langelee had made, especially when he produced a sheaf of accounts that Talerand had inadvertently discovered in the library.

‘The parish barely makes ends meet,’ Langelee crowed, when he happened to see Bartholomew in the orchard. The physician was preparing for a lecture he was to give the following morning, using the trunk of a fallen apple tree as a bench, and enjoying a rare opportunity for solitude. Reluctantly, he closed his book, and made space for the Master to sit next to him.

‘What parish?’ he asked.

‘Huntington,’ replied Langelee impatiently. ‘It was a terrible journey home, what with all those floods, so we have not had time to talk. But you really should study Huntington’s records. Then you will understand what a fabulous bargain I had from those sly vicars. They must be livid!’

‘They will only be livid if they see the accounts,’ Bartholomew pointed out. ‘But they cannot, because you have them.’

Langelee’s jubilant expression faded. ‘I had not thought of that. Do you think I should send them back? Anonymously. Of course.’

‘No!’ exclaimed Bartholomew uncomfortably. ‘Unless you include a hundred marks in the parcel. What you did was dishonest, and I was ashamed to be party to it.’

Langelee waved an airy hand that said he did not care about the physician’s sensibilities. ‘Huntington makes virtually no money at all, and the church has serious structural defects,’ he gloated. ‘It will cost a fortune to rebuild.’

‘But Zouche wanted Huntington to come to Michaelhouse,’ Bartholomew pointed out. ‘And you professed yourself eager to see his wishes fulfilled. How can you justify–’

‘Zouche would have applauded this solution,’ declared Langelee; Bartholomew had no idea if it was true. ‘He did not intend for us to be burdened with an expensive millstone. You can call it payment for our silence over the fact that Cave killed Cotyngham, if it makes you feel any better.’

‘No, it does not, because that was unethical, too. Besides, as I told you in York, I am not sure Cave is sufficiently poised to have committed murder and kept calm when his “victim” was in the Franciscan Friary. Moreover, the shoelace we found in the chimney shows that he searched Cotyngham’s house for documents, but it does not prove him a killer.’

Читать дальше