‘That is an excellent idea,’ said Multone gratefully.

Langelee turned to Bartholomew and Michael. ‘York was my home for a long time, and I owe it to the place to make sure Alice knows what she is doing. You two must go to the library and take those documents to Thoresby. But hurry – the security of your country is at stake.’

Bartholomew was reluctant to leave Langelee to cope with refugees alone, but understood it was important to retrieve the evidence that would convict the spies before it disappeared. Michael sketched a blessing after the Master, and they watched him dart away to where Holy Trinity was a forbidding black mass in the gloom. Then they began striding towards the bridge.

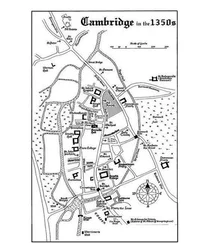

The main road was still crammed with people and animals, all confusion and noise. The water was barely ankle deep, and Bartholomew supposed it had been simple bad luck that they had been incarcerated in the one room in Bestiary Hall that was prone to flood. He glanced up at the sky: dawn was a twilighty glimmer through thick grey clouds.

‘Did Marmaduke come to you with a message?’ he asked of Multone as they went. ‘Telling you to bring armed lay-brothers?’

‘No,’ replied Multone, surprised. ‘Not that I would have been able to oblige anyway – they are too busy with the displaced hordes. Indeed, I should be there now, calming the panic and leading prayers…’

‘We all should,’ said Stayndrop. He was clutching Penterel’s hand to steady himself, and Multone was gripping the Carmelite’s other arm. People were pointing at the unusual sight of a Franciscan and a Benedictine accepting help from a White Friar, and Bartholomew wondered whether their example would begin to heal the damage Wy’s malice had wrought through the years.

They had not gone far when they met Jorden, wet, dirty and harried. The Dominican paddled towards them, and began to speak in an agitated gabble.

‘There is something I should tell you. I only remembered it last night – the first opportunity I have had to consider matters other than theology for an age, because Mardisley is a very demanding opponent. If I let my mind wander for an instant, he–’

‘Tell us what?’ interrupted Michael curtly, eager to be on his way.

‘It is about the codicil giving Huntington to Michaelhouse. I am afraid it does not exist. If my mind had not been so full of the Immaculate Conception, I might have recalled sooner–’

Michael was becoming impatient. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘The clerk charged to draw up the deed was a Dominican, and I was his assistant at the time. We obliged, but Zouche kept ordering us to redraft it – he wanted to ensure it was absolutely right, you see, so as to safeguard Cotyngham. He discussed the wording with all manner of people, and the business took weeks.’

‘Are you saying it was never finished?’ asked Michael, alarmed. ‘That it is incomplete?’

‘We did finish, but Zouche died before it could be signed. Because it was effectively worthless, we scraped the parchment clean, and used it for something else. Ergo , you will never find the codicil, because it does not exist. It never did – at least, not in a form that could help you.’

‘But Radeford found it,’ objected Michael.

‘Impossible,’ said Jorden firmly. ‘But we had better discuss this later, when there are not people needing my help.’

He sped away before Michael could question him further.

‘Radeford suspected there was something amiss with what he found,’ warned Bartholomew, seeing Michael about to dismiss Jorden’s testimony. ‘He said as much – told us he wanted to study it carefully before showing it to anyone else.’

‘But who would forge a document giving us Huntington? It makes no sense!’

Bartholomew shrugged. ‘Perhaps someone who does not like the vicars-choral.’

‘Speaking of Radeford, what did your book-bearer mean when he said he would soon follow him?’ asked Multone, as they resumed their precarious journey. The water was filthy and it stank; Bartholomew was profoundly grateful that the day was still too dark to allow him to see why. ‘He called out as I passed him not long ago, and asked me to give you the message.’

Bartholomew stopped abruptly and stared at him. ‘What?’

‘He was with Marmaduke,’ elaborated Multone. ‘Walking arm-in-arm. He tried to say something else, too, but Marmaduke was in a hurry and would not let him finish.’

‘What did he start to say?’ demanded Bartholomew, speaking with such intensity that the Abbot took a step away from him.

‘I am not sure. He was calling over his shoulder, and we were near the minster, which was noisy.’

‘Please try to remember,’ snapped Bartholomew. ‘It is important.’

‘I thought he mentioned St Mary ad Valvas, but I probably misheard. Why would he be making reference to that horrible place?’

‘What is wrong, Matt?’ asked Michael, alarmed by the physician’s reaction.

‘Cynric,’ replied Bartholomew, stomach churning in alarm. ‘Marmaduke has him.’

The physician began wading quickly towards the bridge. He stumbled when he trod on some unseen obstacle beneath the surface, and the time spent regaining his balance allowed Michael to catch him up.

‘Explain,’ ordered the monk, grabbing his arm to make him slow down. ‘How do you know Marmaduke has Cynric? And what do you mean by “has” anyway?’

‘Cynric is not in the habit of wandering about arm-inarm with strangers,’ replied Bartholomew, freeing himself roughly and ploughing onwards again. ‘So there is only one explanation: Marmaduke was holding him close because he had a knife at his ribs. And the message Cynric gave the Abbot…’

‘That he would soon follow Radeford,’ said Michael, bemused. ‘What did–’

‘Radeford is dead !’ shouted Bartholomew, exasperated by the monk’s slow wits. ‘So Cynric was telling us that he will soon be dead, too. Why could Multone not have mentioned this the moment we were released? We wasted ages chatting about nonsense while Cynric was in danger!’

‘Steady,’ warned Michael soothingly. ‘We will save him. Multone was probably right when he thought he heard Cynric mention St Mary ad Valvas, because we know the place is home to all manner of sinister activities. We shall go there straight…’

He faltered, because they had reached the bridge, which was the scene of almost indescribable chaos. The volume of water racing beneath it was making the entire structure vibrate, and the sound was deafening. Its houses had been evacuated, but the frightened residents had refused to go far, and stood in disconsolate huddles, blocking the road for pedestrians and carts alike. Meanwhile, Mayor Longton had ordered the bridge closed, and a mass of frantic humanity swirled about its entrance, desperate to reach friends and family on the other side.

Bartholomew started to fight his way through them, but the crowd was too tightly packed, and with horror he saw it was going to prevent him from racing to Cynric’s aid. But he had reckoned without the powerful bulk of Michael, and the combined authority of Abbot Multone, Warden Stayndrop and Prior Penterel. The monk was able to force a path where Bartholomew could not, and the other three quelled objections by dispensing grand-sounding blessings in Latin that had folk bowing their heads to receive them.

‘You cannot cross,’ said the soldier on duty, putting out his hand when they reached the front of the melee. ‘It is about to collapse.’

‘But we must,’ cried Michael. ‘We have urgent business on the other side.’

‘Urgent enough to cost you your life?’ asked the guard archly.

‘Yes!’ shouted Bartholomew, shoving past him and beginning to run. He staggered when the bridge swayed under his feet, but then raced on, closing his ears to the unsettling sound of groaning timbers from the houses as the structure flexed. He glanced behind him to see that Michael, Stayndrop, Multone and Penterel had followed, and were close on his heels.

Читать дальше