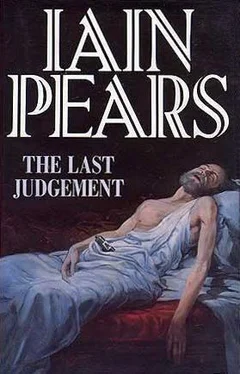

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘How Arthur discovered this I don’t know. And I can’t even begin to guess how some of his fellow pupils at the local school found out. But they did, as kids do, and tormented him. Children are often cruel, and this was 1950, when the memory of the war was still strong. Arthur’s life was sheer hell and there was not much we could do. It was uncertain whom he hated more: his father for what he did, his fellow pupils for persecuting him, or us for concealing it. But from about then all he wanted to do was leave. Get out of the small town where we lived, get out of Canada, and go away.

‘He managed it when he was eighteen. He went to university, then got a job in America. He never lived in Canada again, and never really had much contact with any of us afterwards, except for the occasional letter and phone call. As he grew older I think he accepted more that my parents had done their best; but family life, of any sort, he could never take. He never married; never even had any serious relationship with anyone, as far as I know. He wasn’t strong enough or confident enough. Instead he got on with living and making a success of himself. In work at least, he succeeded.’

‘And then your mother died?’

She nodded. ‘That’s right. Two years ago, and we had to clear out her house. A sad job; all those years of papers and documents and photographs, all to be got rid of. And there was the will, of course. There wasn’t much; my parents had never been rich, but they still treated Arthur as though he was their son, as they always had, even though he’d gone his own way. I think he was grateful for that; he appreciated the effort, even though he couldn’t respond. He came back for the funeral, then stayed to help me clear out the house. We’d always got on well. I think that I was as close to him as anyone ever was.’

‘So what happened?’ Flavia was uncertain whether this detail was necessary; but by now she was caught up in the story. She had no idea what it must have been like to have been Arthur Muller. But she felt for the pain and the sheer loneliness he must have experienced. He was one of the hidden casualties of the war; never appearing on any balance sheet, but still suffering the consequences half a century after the last shot was fired.

‘We found some letters, as I say,’ she said simply. ‘One from his mother, and one from his father. He’d never been allowed to see them. He thought that was the greatest betrayal. I tried to say that they thought it best, but he wouldn’t accept it. Maybe he was right; they had kept them, after all, rather than throwing them away. Anyway, he left the same afternoon. From then on, the few times I phoned him all he would talk about was his hunt to find out about his father.’

‘And the letters?’

‘His mother’s letter he’d brought with him; apparently when he arrived at our house for the first time, he was clutching it in his hand; he’d refused to let it go right the way across Europe and across the Atlantic.’

‘What did it say?’

‘Not a great deal, really. It was a letter of introduction, in effect; written to the friends in Argentina he was sent to first. Thanking them for looking after her son, and saying she would send for him when the world became safer. It said he was a good child, if a little wilful, and took very much after his father, who was a strong, courageous and heroic man. She hoped that he would grow up to be as upright and as honest as he was.’

She paused and smiled faintly. ‘I imagine that was why he got the idea that Hartung was a hero. And why my parents hid it away eventually. It was too bitter, the way she was deluded as well.’

Flavia nodded. ‘And the second letter?’

‘That was from his father. It was written in French as well. I can still remember sitting on the floor-boards in the attic, with him kneeling down, concentrating on the paper, getting more and more excited and angry as he read.’

‘And?’

‘It was written in late 1945, just before he hanged himself. I didn’t find it enormously illuminating, as an outsider. But Arthur was predisposed to interpret anything in a positive light. He twisted the narrative until it meant what he wanted it to mean.

‘I found it a cold, horrible letter. Hartung just referred to Arthur as “the boy.” Said he didn’t feel any responsibility for him, but would look after him when this little problem was resolved. This he was confident of doing, if he could get his hands on certain resources he’d hidden away before he’d left France. I suppose he thought he could buy his way out of trouble. It was a whining letter, describing the person who’d identified him back in France as having betrayed him. Considering what he’d done that was a bit much, I thought. And he said that, if nothing else, the last judgement would exonerate him. I must say, the optimism didn’t carry conviction.’

‘You remember it well.’

‘Every word is engraved on my memory. It was an awful moment. I thought Arthur was going to flip entirely. Then it got worse, as he read and reread.’

‘Why?’

‘I said he’d lived in a fantasy world as a kid. He still did, in a way, only when he grew up he’d learned to subordinate it and keep it under control. It’s not surprising, as I say. Hartung was Jewish. Can you imagine what it must be like to deal with the fact — and I’m afraid it is a fact — that he betrayed friends to the Nazis, of all people? Arthur would do anything not to believe it, to construct an alternative truth. For years he coped by blocking it all out. Then these letters provided him with the opportunity to go back to fantasy.

‘The first thing he latched on to was the reference to judgement. Jews don’t believe in that sort of thing, he said — not that I knew that — so why the reference? Hartung may have got religon in his last days, but not that sort of religion. Therefore the reference must mean something else. Then he switched to this hidden treasure Hartung thought would buy him out of trouble. He never got hold of it; it was hidden where no one would find it. Obviously, QED, the reference to treasure and the reference to judgement were linked. Madness, isn’t it?’

‘Maybe. I don’t know.’

‘Then Arthur left again, and all I got was the occasional progress report from around the world. All his spare moments he devoted to hunting down his father. He wrote to archives and ministries in France to ask for records. He contacted historians and people who might have known his father, to ask them. And he tried to crack the puzzle of his father’s treasure. He got more and more obsessed with that. He said he was building up an enormous file of—’

‘What?’ said Flavia suddenly. It wasn’t that her attention was wandering, although it would have been excusable if it had. But suddenly she was much more engaged. ‘A file?’

‘That’s right. That and the two letters were his two most treasured possessions. Why?’

She thought hard. ‘There was no file that we saw. No letters either. I’ll get them to check again to make sure.’ Somehow she thought it wasn’t going to turn up.

‘I’m sorry,’ she went on. ‘I interrupted. Please continue.’

‘I don’t have much else to say,’ she said. ‘My contacts with Arthur were few and far between. I think I’ve told you all I can. Does any of it help?’

‘I don’t know. Maybe. In fact, almost certainly. Although I think you’ve given us as many new problems as you’ve solved.’

‘Why is that?’

‘It may be — and this is only a guess, which may be wrong — that this is where the picture comes in. You said he became convinced that this reference to the last judgement was a clue.’

‘That’s right.’

‘OK. This picture was part of a series of paintings. Of four paintings on legal themes. Of judgements, in fact. This was the last one to be painted.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.