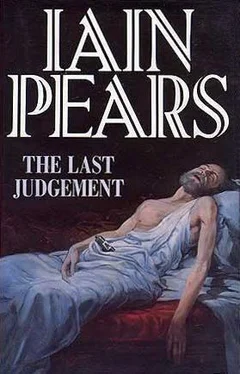

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘We will have to ask this colleague of yours,’ Bottando said. ‘And do quite a lot of other work as well. Muller’s sister arrives tomorrow, I gather. And someone will have to go to Basle.’

‘I can go after I’ve seen the sister,’ Flavia said.

‘I’m afraid not.’

‘Why not?’

‘Ethics,’ he said ponderously. ‘That’s why.’

‘Just a second—’

‘No. You listen. You know as well as I do that you really ought to take a low profile in this matter. However unwittingly Mr Argyll here may have been handling stolen goods, none the less that is what he may well have been doing. He is also a major witness and you concealed that from the Carabinieri.’

‘That’s overdoing it a bit.’

‘I am merely stating what it would look like in the hands of someone like Fabriano. You cannot be seen to be involved in the investigation.’

‘But—’

‘Be seen to be involved, I said. There is also another problem, which is that, for the first time in our acquaintance, brother Janet is not being entirely frank with me — and until I know why, we will have to proceed with some caution.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘He said that it would be best if Mr Argyll brought the picture back.’

‘So?’

‘I never told him Mr Argyll had the picture. Which leads me to suspect that maybe there was a Frenchman working here without official notice. Which I don’t like. Now, Janet never does anything without a good reason; so we have to try and work out what that reason is. I could ask, but he’s already had the opportunity to tell me, if he was so minded.’

‘So,’ he continued, ‘we must plod along methodically. Mr Argyll, I must ask you to return that picture. I hope you won’t find that too much of a burden?’

‘I suppose I could manage,’ he said.

‘Good. While there, you might arrange a tactful meeting with your friend Delorme and see if he can shed any light on this. But do not, under any circumstances, do anything else. This is a murder case, and a nasty one. Don’t stick your neck out. Do your errand and come straight back. Is that understood?’

Argyll nodded. He had not the slightest intention of doing anything else.

‘Good. In that case, I suggest you go and pack. Now, Flavia,’ he went on, as Argyll, realizing he was no longer wanted, got up to go, ‘you will go to Basle and see what you can find out. I will tell the Swiss you are coming. You will then come straight back here as well. Anything else you do will be unofficial. I don’t want your name on any report, interview or official document of any sort. Understood?’

She nodded.

‘Excellent. I will tell you what Muller’s sister says when you get back. In the meantime, I suggest you go round to the Carabinieri to deliver Argyll’s statement, and see if you can persuade them to let you have a look at what they’ve accumulated so far. You don’t want to miss something in Basle because you don’t know what to look out for.’

‘It’s nearly eleven,’ she pointed out.

‘Put in an overtime claim,’ he replied unsympathetically. ‘I’ll have all the bits of paper you need in the morning. Come and get them before you go.’

7

Six o’clock in the morning. That is, seven hours and forty-five minutes since he got in, seven hours and fifteen minutes since he went to bed. Not a wink of sleep and, more to the point, no Flavia either. What the hell was she doing? She’d gone off with the Carabinieri. And that was the last he’d heard. Normally Argyll was a tranquil soul, but Fabriano had irritated him beyond measure. All this muscular masculinity in a confined space, the sneering and posturing. What, he wondered for the tenth time, had she ever seen in him? Something, evidently. He rolled over again, eyes wide open. Had she been there, Flavia would have informed him dourly that all he was suffering from was a bad case of over-excitement, dangerous in someone who liked a quiet life. Murders, robberies, interviews, too much in a short space of time. What he needed was a glass of whisky and a good night’s sleep.

With which diagnosis he would have agreed, and indeed he had been agreeing with it all night, as he tossed and turned. Go to sleep, he told himself. Stop being ridiculous. But he couldn’t manage either and, when he could no longer endure listening to central Rome’s limited bird population saluting the morn, he admitted final defeat, got out of bed and wondered what to do next.

Go to Paris, he’d been told, so maybe he should. If Flavia could absent herself in such an inconsiderate way, he could demonstrate this was no monopoly of hers. Besides, it would get an unprofitable task over and done with. He looked at his watch as the coffee boiled. Early enough to get the first plane to Paris. There by ten, get the four o’clock back and be back home by six. If planes, trains and air-traffic controllers were in a co-operative mood, that is. He only hoped the nightman at the Art Theft Department had instructions to allow him to take the painting away. If he was fortunate, he could be back by evening. And then he could go and see about that apartment. If Flavia didn’t like the idea, then tough.

So, his decision made, he scrawled a hurried note and left it on the table as he walked out.

About twenty minutes after he went out, Flavia came in. She too was utterly exhausted, although for different reasons. A long haul. It was amazing how much paper these police could generate in such a short time, and Fabriano had fought hard to avoid giving it to her. It was only when she’d threatened to complain to his boss that he reluctantly gave way. Had she been in a better mood, or less tired, she would just about have seen his point. He was working long hours on this case. It was his big chance, and he wasn’t going to let it get away. He certainly wasn’t going to share the credit with her if he could avoid it. The trouble was, his attitude had the effect of hardening hers. The more he resisted, the more she demanded. The more he — and Bottando, in fact — wanted to keep her out, the more she was determined to take it further. So she’d sat and read. Hundreds of sheets of paper, of interviews and documentation and snapshots and inventories.

But for all the vast quantities of information, there was little of any importance to be discovered. Meticulous lists of the contents of Ellman’s hotel room produced nothing of any interest at all. Preliminary enquiries indicated no criminal record in either Switzerland or Germany; not even a driving offence to besmirch his good name. Then there was a mound of interviews, taken after they had gone back to Bottando’s office. Waiters, doormen, passers-by, visitors to the hotel restaurant and bar, cleaners and guests. Starting with a Madame Armand in the room opposite who believed she may have caught a glimpse of Ellman that morning, but who spent more time complaining loudly about missing her plane than offering useful clues, right through the alphabet to Signor Zenobi who confessed, with much guilt, that he had been entertaining a, ah, friend and didn’t listen to anything and there wasn’t any need for his wife to know anything about this, was there?

After hours of concentrated reading, Flavia gave up and walked home to talk it over with Argyll in the short space of time before she disappeared to Switzerland.

‘Jonathan?’ she called in her sweetest of voices as she let herself in. ‘Are you awake?’

‘Jonathan?’ she said a little more loudly.

‘Jonathan!’ she shouted when there was still no reply.

‘Oh, bugger,’ she added when she glanced down and saw his little note on the table. Then the phone went. It was Bottando, wanting her in his office as soon as possible.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.