‘Over there,’ Kyukov indicated a concrete signal box with a shell hole and half its roof blown away.

‘When the whistle goes,’ Pyotr agreed.

It went, and all but two of the first hundred poorly armed conscripts raced up a slippery bank and on to the twisted tracks, with only ‘Not one step back’ shouted from behind to disturb them until the machine guns opened up ahead and they started falling, their rifles unfired and grenades unthrown. Those behind snatched up weapons, as ordered, and died in turn, cut down like screaming wheat.

‘Fuck. Fuck. Fuck…’ Kyukov scrambled up the steps and collapsed on the floor. Pyotr crawled over him and peered out through a crack. Behind him the Tartar was still swearing. Kyukov had never been in a fight he couldn’t win. Pyotr knew this. It was one of the reasons they were friends.

This was different.

‘We’re going to die here.’

Pyotr shook his head. ‘No, we’re not. We’re going to become heroes.’

Enough blood had been spilt for patches of snow, ice and churned-up earth to smoke, steam rising from puddles in ever diminishing wisps until the blood cooled.

Snow fell. An hour later, with darkness also falling, an artillery barrage lit the sky to one side of them, and they could see that the bodies in the more exposed areas had become mounds, indistinguishable from the earlier snow.

‘Heroes?’ Kyukov said.

Pyotr smiled. He’d been waiting for the question.

‘They keep heroes alive. That’s why we’re going to become heroes, so we can stay alive.’ He could tell, looking into his friend’s wide face and dark eyes, that he didn’t get it, didn’t understand how it would work.

‘I’m hungry,’ Kyukov said.

‘We had breakfast,’ Pyotr reminded him.

Kyukov grumbled, and Pyotr went back to examining the rows of metal levers that had once changed points on the track, trying to imagine this place as part of a normal station with unbroken rails and trains to take him elsewhere. A man might have to live a long time before that happened.

His way was better.

The enemy’s side of the tracks was in darkness, but the glow of a fire showed from inside a machine shop with sandbags piled high at the front. A loudspeaker in a broken window above blared bad Russian across the gap, suggesting that they surrender and promising Red Army soldiers shelter, warm clothing and food.

Swiftly, a loudspeaker fired up on the Soviet side.

Soviet citizens did not surrender. There was no man here who wouldn’t willingly give up his life for the Boss. It was the Germans who’d die here, forgotten by their wives, who were being fucked by filthy foreigners as their husbands froze or lost their balls to Russian bombs.

‘You think that’s true?’

‘Wouldn’t you worry about what was going on back home?’

‘You think the Germans would really give us food if we surrendered?’

‘I think they’d put us up against a wall. Our side certainly would if they caught us going over to the enemy.’

‘Pyotr,’ Kyukov said, ‘look…’

‘At what?’ he said crossly.

‘To the left. Wait for the next flare.’

Below them, in the lee of a broken wall that kept him free from drifting snow, a Russian sergeant lay, his face shrunken back to the skull. It was his watch Kyukov had spotted, gold by the look of it, looted from a German most likely. It wouldn’t buy their way out but it had the makings of a bribe. ‘Go and get it,’ Pyotr ordered.

Kyukov shook his head.

‘I’ll whistle if anything moves.’

‘It’s too risky,’ Kyokov said.

‘Oh well, if you’re scared…’

Slithering down the steps, feet first, keeping his body tight to the cold concrete, Pyotr Dennisov prayed that his movements were invisible.

A day in battle and he already feared the enemy’s snipers. He was also furious at having trapped himself into doing this. At ground level, he edged around the base of the signal box, knowing that he was now exposed, with only his resemblance to one corpse among hundreds to keep him safe.

Cold had reduced the sergeant’s corruption to a slow crawl. His eyes were gone, liquefied or taken by crows, his nostrils leprous and his teeth bared. He smelled of sour milk and frost had glued him so tightly to the ice that bits of his face came away when Pyotr rolled him over. Inside his jacket were photographs, folded letters and a silver cigarette case. Pyotr left the photographs and letters.

The leather of his watch strap was so frozen that it cracked slightly when Pyotr unbuckled it. He was turning to go when he hit his kneecap hard, the shock sending black waves through him. A rifle, bigger than any he’d seen.

The Russian corporal clutching it didn’t want to give it up. Resting flat to the ground, Pyotr tugged again and kept tugging until the rifle slid out from under its previous owner. Pyotr’s breath rose like steam.

How could they miss seeing him?

A flare went up and he hugged the ground, pushing in against the corporal, with the rotting sourness of the sergeant on his other side. He shut his eyes tight against a bullet that never came. After a minute’s brightness, he sensed darkness return and night shuffle in from the shadows.

‘What’s that then?’

Pyotr rested the rifle casually in the corner.

‘What do you think?’ He weighed the watch and the cigarette case in his hands, changing his mind about using the watch as a bribe. This left the question: which did he want? The watch was gold, with a dial that was white and shiny, but the silver cigarette case held cigarettes, black ones with a gold band above each filter.

‘Here,’ Pyotr Dennisov said, throwing Kyukov the watch.

His friend flashed him a grateful grin.

Later that night, after Kyukov had set his watch to what Pyotr thought was roughly the right time, they sat with their backs to the wall, smoking a German cigarette between them, and Kyukov suggested a way out of there.

‘Across the river,’ he said.

‘You’ll be shot by our side.’

‘Then let’s go by land.’

‘And be shot by Germans? No, stick with me. I’ll get us out of here.’

Kyukov would stick with him, they both knew that.

They were just talking.

A cigarette against the darkness, and talk to fill silences that were almost more unnerving than the shelling and the crack of sniper fire.

First thing next day the Germans launched an attack on the siding and were beaten back. Their bombers came that afternoon, a long line of grey planes with black crosses on the wings. They started dropping their load half a mile back and the line of explosions ran straight towards the hut.

‘We stay,’ Pyotr said.

The older boy looked at him, his eyes uncharacteristically mutinous.

‘We stay together. We stay here.’

‘Pyotr…’

‘What do you think they’ll do to us if they discover we’ve been hiding in here since yesterday?’ They both knew he was talking about their own side.

‘They might feed us first.’

Pyotr took that as surrender.

Kyukov sat with his back to the approaching bombers, his arms wrapped around himself as if that could provide protection. And then, when the planes were past, the last of the German bombs falling into the Volga, he vomited.

‘I’m hungry,’ he said.

‘We’re both hungry.’

‘I bet they have food.’ He jerked his head towards the Nazi side. ‘They said they had food.’

‘They were probably lying.’

No one attacked next day and no bombers flew over the sidings, and all that happened was that Pyotr and Kyukov smoked the last of the stolen cigarettes. The day after that, they watched a German sniper in the ruins of a factory opposite kill half a dozen Soviet soldiers in a communication trench.

Читать дальше

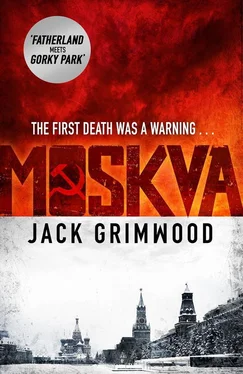

![Георгий Турьянский - MOSKVA–ФРАНКФУРТ–MOSKVA [Сборник рассказов 1996–2011]](/books/422895/georgij-turyanskij-moskva-frankfurt-moskva-sborni-thumb.webp)