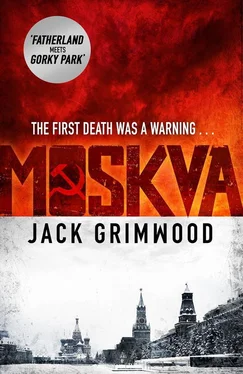

He’d looked at her, wondering.

‘Here,’ the boy opposite suddenly said.

Several people glanced round to see him offer to share his vodka. A handful of those looked hopeful, perhaps believing the Stolichnaya might come their way. It didn’t. Tom took a hefty swig and let most run back, returning the bottle with a nod.

‘Going or returning?’ Tom asked.

The conscript’s grin was an answer in itself.

Five minutes later, the boy was deep in a long and one-way conversation about a bar brawl in Minsk. A minute after that, he was showing Tom a scar, which was still raw and curved, a hand’s breadth above his hip from his belly to his back. As night drew in, the passengers settled, the main lights went down and half-lights came on, and the carriage might have been brighter, if most of those hadn’t been broken, stolen or simply never replaced. Like birds roosting, people dropped off to sleep until only Tom, the kid with the scar and a girl who’d moved next to him after he told the story about the knife fight were awake.

In the end, Tom took pity on them and shut his eyes too.

The kids were discreet. You had to give them that.

Of all the things Tom might have felt, sadness was the most unexpected. Not at what they did but at the youth and innocence that let them do it. You needed both to be them. Tom knew, even before the diesel made an unscheduled stop just outside Volgograd, and the old woman and small boy went to the door to wave to militsiya officers who came aboard to usher Tom off, that if he could buy Alex the chance to be young and behave as badly, he would.

A Tartar in a tatty flying jacket, with its collar up, was waiting by the entrance. The man was grinning and Tom understood he was the joke. The man’s eyes were black and unblinking, so flat it felt like looking into a void.

When he nodded to the militsiya , they let go of Tom’s upper arms and stepped back, turning for the exit without saying a word. The man watched them go for a moment, his expression unreadable, then he gestured for Tom to step closer.

Without losing the grin, he said, ‘You do what I say or we kill the girl. Understand?’

‘Of course. I understand.’

‘Now. You have the photographs?’

‘I have the photographs.’

‘Show me.’

‘When I’ve seen Alex.’

‘One photograph. To prove you have them.’

‘You really think I’d come all this way without them?’

‘You’d be unwise to.’ The Tartar turned away and an old woman brushing snow off the opposite platform with a twig broom glanced over, hunched her shoulders and hurriedly went back to work. Some things it was safer not to see.

‘You liked my present?’

Tom stared back impassively.

‘That cat. I particularly enjoyed my share of the skin. Fiddly, removing all that hair, of course. But worth the effort.’ His grin widened as they headed out of the station.

‘Your transport awaits.’

Tom stared in disbelief at the open-top Jeep the Tartar indicated. It had snow tyres and metal front seats, no seats at all at the back, and its side windows at the front were wound down. There was nothing to protect him from the cold.

A short drive brought them to an apartment block at the river’s edge.

‘Alex is here?’

‘You think we’re fools?’

Broken bricks had been built into a wall that hugged the building’s edge like ivy. Cut into them were the words Not One Step Back.

‘You know where we are?’

Tom shook his head.

‘You should. You know why the French surrendered? Because they were weak. You know why the Germans surrendered? Because they were weak. Sergeant Pavlov wasn’t weak. He became what he had to become. We all did. Pavlov held this building against Nazi tanks, bombers and infantry for a month.

‘All his food,’ said the Tartar, ‘all his drinking water, ammunition…’ He turned to look at the frozen river. ‘All of it came across that under attack from enemy planes. The Nazis lost more men trying to take this building than taking Paris… Volgograd. ’ He spat, phlegm sliding on ice at his feet. ‘What sort of fools rename Stalingrad?’

‘You were there?’

‘In this house?’ The Tartar shook his head.

‘But you were at Stalingrad?’

There was something hard, entirely inhuman in the man’s stare. He looked again over the frozen waters of the Volga and Tom knew that what he saw himself wasn’t what this man saw. ‘We learned to kill. We learned to like killing. After the war, they wanted us to go back to being who we’d been before.’

‘You couldn’t?’

‘No one could. You really didn’t recognize me?’

‘Not until you mentioned the cat.’

‘You’re sure you have the photographs?’

He was the one grinning at the camera when Golubtsov was tied to a chair. The one holding the board in front of an oak tree from which four German teenagers hung, a board that read The Tsaritsyn Boys . In an earlier, more innocent picture he’d been peering at the engine of a captured Panzer, his hands streaked with oil, while the others simply posed.

‘Kyukov,’ Tom said. ‘You were their engineer.’

‘Mechanic. I was their mechanic.’

‘General Dennisov’s friend.’

Again that half-look into the distance as if sifting memories or consulting with ghosts. ‘His oldest,’ Kyukov said. ‘His best.’

Tom shivered.

Beyond Pavlov’s House, beyond the city, beyond the reach of pylons and factories and other signs of civilization, the river’s edge made the landscape timeless as a faded photograph. Tom was grateful when the forest began. Until the darkness and tightness of the trees started to press in, and he wished they were by the river again, for all the wind blowing across it had been vicious.

Colonel Kyukov was dressed for the drive: pale leather jacket with sheepskin lining, dark leather jeans and heavy-heeled boots. He could have stepped from the turret of a T-34 or ridden out from between the trees on a pony with ice clinging to its mane. His flying jacket was good against the wind, and its leather tough enough to turn a blade. Tom’s own jacket was Soviet, chosen to blend in on the train, and next to useless.

The snowfall began shortly after they left the city, just a few flakes at first, softening the air in front of them. They built up on the windscreen until Kyukov swore and flicked on the wipers, sending clumps of snow into their faces as the screen cleared and he increased speed again.

‘Where are we heading?’

‘You’ll see.’

The Volga came back into sight where it began a huge turn, the river’s far edge vanishing as it widened. Without signalling, without saying anything, Kyukov turned down a track to a ruined checkpoint, its bar pointed skyward like an accusing finger, its barrel weight buried in fallen snow.

A sign said go no further.

Falling snow was meant to make weather warmer. But when Tom began to feel warm, he knew it was the blood retreating from his limbs as his veins narrowed and his body began to shut down to protect its core. When he found himself fighting sleep and a desire to curl into a ball, he realized hypothermia was close.

‘Tiring journey?’ Kyukov’s glance was knowing.

‘I’m fine,’ Tom said.

‘For now.’

The Tartar returned his attention to the track.

Beyond the checkpoint, razor wire fenced a landing stage off from the firs. Scrub poking from the snow filled the fifty paces between the woodland’s edge and the fence. Rusting searchlights on sentry towers told Tom guards had once policed that gap. Absolutely No Entry announced a sign.

Читать дальше

![Георгий Турьянский - MOSKVA–ФРАНКФУРТ–MOSKVA [Сборник рассказов 1996–2011]](/books/422895/georgij-turyanskij-moskva-frankfurt-moskva-sborni-thumb.webp)