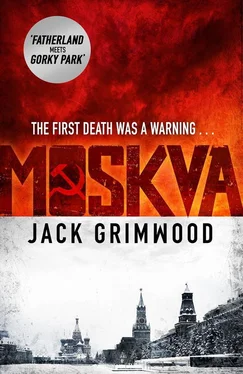

He’d expected Soviet tradecraft to be better.

‘Here.’ The old woman offered Tom what looked like a sliver of ivory.

It was an angel carved from wax. Squat and moon-faced, unnervingly ugly, with a bent wing.

Distractedly, Tom dug into his pocket for change. He shook his head when she pushed the figure at him. ‘Sell it again,’ he suggested.

‘That would be bad luck.’

Her accent was hard. She might be southern, to judge from her leathery face and the sharpness of her cheekbones. Georgian? Azerbaijani? Tom’s Russian was too rusty for him to place her. He was pleased enough to understand the words.

‘So,’ she said, ‘what’s your name?’

‘Why?’ Tom demanded.

‘I was being polite.’

Despite himself, Tom grinned.

‘See. That’s better. Can you spare one of those?’ She nodded at the burned-out papirosa in his fingers. And taking one for himself, Tom gave her the packet. As he was leaving, she called after him.

‘If not American?’

‘English…’

‘Covent Garden. The Royal Ballet. Sadler’s Wells.’

Hard walking on slippery pavements brought him to the Garden Ring and the Sadovaya Samotechnaya block for foreigners that stood in its shadow. As he approached, a black cat hurried between ruts in the snow, dodged round the KGB man guarding its entrance and mewed for the gate to be opened.

‘He lives here?’ Tom asked the guard, who did his best not to be shocked that Tom spoke his language.

‘I’m not sure he has papers.’

Tom laughed.

The man couldn’t help glancing beyond Tom to his shadow, who was now pretending to admire a bronze statue of a Soviet youth in gym shorts holding the hand of a girl in a summer dress. When the boy felt he’d admired the statue for as long as was believable, he knelt and tied his shoelace for the fifth time that evening.

Tom could lose him easily.

But the Committee for State Security would assign someone better. Then, when Tom really needed to shake free – if he ever really needed to shake free – it would be harder.

‘Where’s a good place to drink?’

‘Everywhere is closed.’

‘It’s New Year’s Eve.’

‘In Moscow, bars close at eleven.’

‘Tovarishch. Comrade … Don’t be ridiculous. It’s New Year’s Eve. There must be a bar open somewhere in this city.’

The KGB man sighed.

Lights still shone in at least half the flats overlooking the bleak street, but its cafes and shops were firmly shut. He’d just decided he must have overshot the address he’d been given – along with a warning about foreigners not necessarily being welcome, New Year’s Eve or not – when a man shouted from a concrete walkway above, and a familiar noise brought Tom up short.

He knew the sound of a door being kicked open.

He’d heard enough of that in Northern Ireland. Usually, though, the kick came from outside. This time… Tom heard the door slam into a wall and saw a man’s body tumble down the concrete stairs to land in a sprawl.

Behind him stamped a broad-shouldered man in his twenties, his torso bare except for a stained singlet. What Tom noticed, though, was his leg. It was missing, its replacement constructed from the leaf spring of a vehicle. Having dragged his victim to his feet, the man hurled him into a bank of snow and finally noticed Tom watching.

‘What are you looking at?’

‘You,’ Tom said.

The man considered that.

‘Do I look like I play Abba?’ he asked furiously. ‘I mean, really? The Beatles, if you must. The Stones, back when they were good. New York Dolls. The Cramps. The Ramones. But Abba?’

‘Always hated them,’ Tom said.

‘You lost?’

‘Who isn’t? No. I’m looking for a bar.’

The man jerked his head towards the stairs down which the drunk had been thrown. ‘There are worse ones than mine. Not many, mind you…’

‘I’m not that choosy.’

The upstairs bar had a long length of battered zinc against which a dozen men leaned. Another four formed a queue behind a fifth, who stood in front of a computer monitor with a filthy screen. The fifth man was battering a keyboard as he tried to twist the shapes that rained from above. When he mistimed a move, falling blocks built up and his screen filled. Cursing, he stepped aside for the man behind to take his place.

‘Tetris,’ the bar owner said sourly. ‘Worse than heroin.’

‘Where did the computer come from?’

‘The army.’

‘Do they know it’s gone?’

‘They’ve probably replaced it.’

The man who’d just lost his game yelled a food order.

Instead of answering, the one-legged man took himself behind the zinc and vanished through a curtained gap in a wall of records. Mostly albums, although a row of 45s sat high up. He returned with a bowl of red cabbage, which he thrust at the loser with a shrug that suggested personally he wouldn’t eat it. Then he headed for a battered turntable on a shelf attached to the record wall.

‘Any requests?’

There was silence from the room.

‘Yeah,’ Tom said. ‘“Sympathy for the Devil”.’

The barman stared at him.

‘Could have been written about any of us,’ said Tom. ‘Apart from the bits about wealth and taste.’

Straight after came ‘Stray Cat Blues’.

‘To Behemoth,’ said the one-legged bar owner. ‘Sadly absent.’

Then the man put away Beggars Banquet , pulled out David Johansen and played ‘Frenchette’ twice before lowering the needle on to a badly scratched 45 of The Damned’s ‘New Rose’ . In between, he served flasks of vodka and iced bottles of Zhigulevskoe lager to a slowly dwindling crowd that finally comprised only a hard core of drinkers and those too drunk to find the door.

There were no seats in his bar, no tables.

His customers were restless and cheaply dressed and stank of the vinegary cabbage ferried endlessly from the kitchen. Sweat, vodka and cigarette smoke soured the room. Anyone who believes vodka doesn’t smell hasn’t sweated it out. After a flask and a half, Tom finally cracked and asked for a bowl of whatever everyone was eating.

The bar owner shouted and a whey-faced teenager came in from the kitchen. She scowled at the owner, looked over at Tom and her eyes flicked towards the papirosa he was lighting. Tom realized it wasn’t the cigarette that attracted her.

It was the flame…

The cabbage she dumped at his elbow was sweet and sour and tasted of raisins. Its welcome warmth reminded him of hunger. Of being cold and fed up, cold, fed up, wet and hungry. Without thinking, he went to the window and stared down at his KGB shadow. The man was stamping his feet in a doorway, his donkey jacket wrapped as tightly round him as it would go. Cold nights in dark doorways.

Worse nights in the wastes of a Belfast multi-storey.

The wind blowing through him, whistling between his ribs, while he pissed in a milk carton and shat in a supermarket bag, waiting for a man who didn’t show and men who wanted to kill him, who did.

There’d been women over there. When the nights were darkest, they’d put warmth in his bed. Only one of them had realized it wasn’t the sex he needed. She’d cradled his head as he cried through a long December night, and never referred to it again. That was ten years ago. Her man came out of prison eventually. Around the time her son went in.

‘Who is he?’ the bar owner asked.

‘KGB. My shadow.’

‘You American?’

‘English.’

The bar owner looked doubtful.

‘Promise you,’ Tom said. ‘English.’

The man brought Tom another beer and a fresh flask of vodka, waving the payment away. ‘What brings someone like you to a bar like this?’

Читать дальше

![Георгий Турьянский - MOSKVA–ФРАНКФУРТ–MOSKVA [Сборник рассказов 1996–2011]](/books/422895/georgij-turyanskij-moskva-frankfurt-moskva-sborni-thumb.webp)